We’ve talked about understanding the various kind of תהילים, and my model, based on the Zohar:

| מאמר של שבח | ספירה |

|---|---|

| אישור | כתר |

| שיר | חכמה |

| זמר | בינה |

| ברכה | חסד |

| נגון | גבורה |

| הלל | תפארת |

| נצוח | נצח |

| הודאה | הוד |

| רינה | יסוד |

| תפלה | מלכות |

I would like to look at some תהילים that have more than one מאמר של שבח in the כותרת, specifically למנצח מזמור לדוד.

We looked at מזמור last time, in Into Pruning Hooks. To quote myself:

I associate מזמור with the ספירה of בינה, analytic wisdom, which goes with the מידה of דין. A מזמור is a psalm of ה׳'s transcendence, separation from us. Rav Hutner explains:

…”זמרה“ ענינה לשון קילוס. ועוד עניין אחד מצינו בשורש תיבת זמרה, שמתפרש הוא גם בלשון הכרתה, וכגון זומר דל״ט מלאכות…והיינו שקילוס והכרתה יש להם שורש משותף, מפני שהכרתת הרגשת ישותו של הקטן בפני מי שגדול ממנו, היא היא קילוסו של הגדול…וכאן הוא ההבדל בין השיר של עבודת השם ובין המזמור של עבודת השם. דהשיר הוא ביטוי התענוג של הרגשת ההשתייכות וההמשכה, והמזמור הוא ביטוי התענוג של הרגשת הנשגביות וההפלאה.

In other words, שיר is a celebration of אהבת ה׳; זמרה is a celebration of יראת ה׳.

We looked at למנצח in Let’s Get Together, and I quote that discussion:

שְׁבִיעָאָה [ספירת נצח] בְּנִצּוּחַ, דְּאִיהוּ נֶצַח יִשְׂרָאֵל, וַעֲלֵיהּ אִתְּמַר (שמואל א טו:כט) וְגַם נֵצַח יִשְׂרָאֵל לֹא יְשַׁקֵּר…

And as a ספירה, a manifestation of the divine in the universe, it is connected to חסד:

חסד וגבורה הן השורשים לספירות נצח והוד, ועל כן נקודת המוצא צריכה להיות בחסד ובגבורה…

הנצח וההוד הן ביטוי ותולדה של החסד והדין. מדובר בתנועה, במגמה, ואולי אף נאמר תוצאה, של הנהגת החסד והדין…

שם זה משותף לשתי הספירות וההבחנה ביניהן נעשית על פי השם הנלווה לשם זה: ד׳ צבאו־ת או א־לקים צבאו־ת. הצבאות הן כח, אלו הן חיילותיו של קוב״ה ובהם משתמש כביכול הקב״ה כדי להוציא אל הפועל את רצונו…

נצח, as I put all this together, is the manifestation of ה׳’s חסד through intermediaries, through us. But the ספירות are supposed to be not abstract theological constructs, but inspirations for our own lives. When we do חסד, that is ה׳'s manifestation in נצח but our manifestation of חסד. Human beings manifest נצח by inspiring others to do חסד, by being leaders. Hence the term מנצח, not “victor” but “conductor”. It’s the multilevel marketing scheme of מדה development. And the connection to נצח meaning eternity, is that this ספירה represents the ultimate goal of creation.

G-d’s primary purpose in creation was that He should be able to reveal Himself to His handiwork, this being the greatest good that He can bestow. This is then the level of Netzach-Victory, the primary purpose.

We exist to be ה׳'s conduit for חסד, and למנצח is addressed those who would be leaders, in the terms of חז״ל, פרנסים לדור.

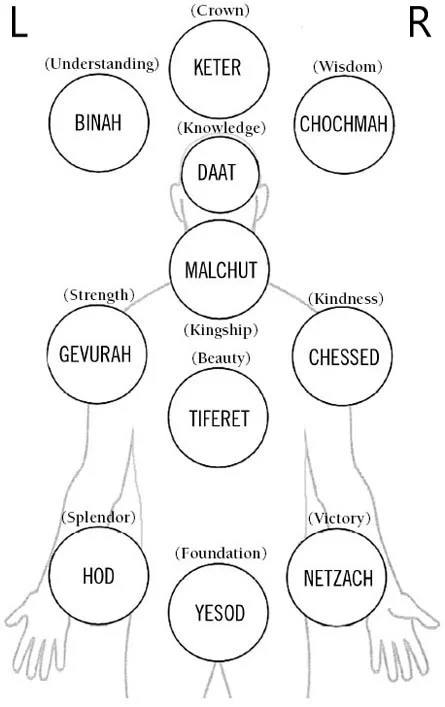

There is a metaphor for the ספירות as parts of the human body:

בינה is the left brain (in modern neuroanatomy, the analytical side of the brain; a fun coincidence) and נצח is the right thigh, which (in another fun coincidence) is actually controlled by the left brain (the nerve pathways cross from left to right in the medulla). למנצח מזמור is a celebration of ה׳‘s מידת הדין manifesting in human חסד. Acknowledging ה׳’s judgment allows us to be less judgmental, and appreciating ה׳'s transcendence brings us to appreciate the essential unity of all mankind.

The former is expressed in the pasuk:

מִדְּבַר שֶׁקֶר תִּרְחָק; וְנָקִי וְצַדִּיק אַל תַּהֲרֹג כִּי לֹא אַצְדִּיק רָשָׁע׃

And the latter is expressed in תהילים פרק ח, which we will look at later.

The first perek I want to look at is למנצח בנגינות מזמור, with three מאמרות של שבח. נגון in my model corresponds to the מידה of גבורה:

חֲמִשָּׁאָה [ספירת גבורה] בְּנִגּוּן, בְּגִין דְּהַאי נִיגוּן סָלִיק מִנֵּיהּ כַּמָּה נְגִינוֹת, עוּלֵימָן מִסִּטְרָא דִשְׂמָאלָא, דְּמִתַּמָּן רוּחַ צָפוֹן הֲוָה נָחֲתָא בְכִנּוֹר דָּוִד וַהֲוָה מְנַגֵּן מֵאֵלָיו, הֲדָא הוּא דִכְתִיב (מלכים ב ג:טו) וְהָיָה כְּנַגֵּן הַמְנַגֵּן [וַתְּהִי עָלָיו יַד ה׳].

גבורה: הספירה המנוגדת לחסד. הגבורה מצמצת את השפע וההארות אך ורק למי שראוי לה ועל פי מעשי האדם…לכן הספירה נקראת גם ”דין“ ו”פחד“.

Both מזמור and נגינות reflect the kabbalistic סִטְרָא דִשְׂמָאלָא, the “left side” of the עץ החיים, what we otherwise call ה׳'s מידת הדין, so I don’t think it changes the overall sense of the introduction of the perek.

א למנצח בנגינות מזמור לדוד׃

ב בקראי ענני אלקי צדקי בצר הרחבת לי; חנני ושמע תפלתי׃

ג בני איש עד מה כבודי לכלמה תאהבון ריק; תבקשו כזב סלה׃

The Radak connects this perek with the previous one:

מזמור לדוד; בברחו מפני אבשלום בנו׃

בקראי ענני אלקי צדקי: הנכון שנאמר המזמור הזה גם כן בברחו מפני אבשלום. ואמר: ”בקראי ענני אלקי צדקי“, שאתה יודע כי עמי הצדק, ועם אשר כנגדי העול והחמס, ואתה אלקים שופט עלינו.

But what makes this different from most פרקי תהילים is that he doesn’t go on to address ה׳; he is talking to his enemies. He’s acting as the מנצח, the conductor, telling them what to do:

ד ודעו כי הפלה ה׳ חסיד לו; ה׳ ישמע בקראי אליו׃

ה רגזו ואל תחטאו; אמרו בלבבכם על משכבכם; ודמו סלה׃

The gemara understands that there are stages in self-improvement:

אמר רבי לוי בר חמא, אמר רבי שמעון בן לקיש: לעולם ירגיז אדם יצר טוב על יצר הרע, שנאמר: ”רגזו ואל תחטאו“. אם נצחו—מוטב, ואם לאו—יעסוק בתורה, שנאמר: ”אמרו בלבבכם“. אם נצחו—מוטב, ואם לאו—יקרא קריאת שמע, שנאמר: ”על משכבכם“. אם נצחו—מוטב, ואם לאו—יזכור לו יום המיתה, שנאמר: ”ודמו סלה“.

He’s not fighting his enemies; he’s offering them advice!

And then David turns back to ה׳:

ו זבחו זבחי צדק; ובטחו אל ה׳׃

ז רבים אמרים מי יראנו טוב; נסה עלינו אור פניך ה׳׃

ח נתתה שמחה בלבי; מעת דגנם ותירושם רבו׃

ט בשלום יחדו אשכבה ואישן; כי אתה ה׳ לבדד; לבטח תושיבני׃

This isn’t a psalm of דין, it’s one of חסד—we all will live בשלום יחדו, with שמחה בלבי.

Feivel Meltzer, in פני ספר תהלים, notes that this is a psalm of the evening: אמרו בלבבכם על משכבכם and בשלום יחדו אשכבה ואישן. The next perek is another למנצח מזמור לדוד but it is a psalm of morning: בקר אערך לך ואצפה. ספר תהילים is, at its core, the סידור of the בית המקדש, but these are almost proto-ברכות קריאת שמע.

ושננתם לבניך ודברת בם בשבתך בביתך ובלכתך בדרך ובשכבך ובקומך׃

And the evening prayer asks not for ה׳'s judgment on the רשעים, but their improvement.

רִבּוֹנוֹ שֶׁל עוֹלָם הֲרֵינִי מוֹחֵל לְכָל־מִי שֶׁהִכְעִיס וְהִקְנִיט אוֹתִי אוֹ שֶׁחָטָא כְנֶגְדִּי…

א למנצח אל הנחילות מזמור לדוד׃

ב אמרי האזינה ה׳; בינה הגיגי׃

ג הקשיבה לקול שועי מלכי ואלקי; כי אליך אתפלל׃

ד ה׳ בקר תשמע קולי; בקר אערך לך ואצפה׃

This תפילת בוקר is less kumbaya than the previous one.

ה כי לא א־ל חפץ רשע אתה; לא יגרך רע׃

ו לא יתיצבו הוללים לנגד עיניך; שנאת כל פעלי און׃

ז תאבד דֹּבְרֵי כזב; איש דמים ומרמה יתעב ה׳׃

That’s part one. The second half of the perek returns to David’s peace of mind because ה׳ will judge his enemies. Again, ה׳‘s מידת הדין allows for human חסד.

ח ואני ברב חסדך אבוא ביתך; אשתחוה אל היכל קדשך ביראתך׃

ט ה׳ נחני בצדקתך למען שוררי; הושר (הישר) לפני דרכך׃

The perek goes back and forth between the punishment of the wicked and the peace of the righteous.

י כי אין בפיהו נכונה קרבם הוות; קבר פתוח גרנם; לשונם יחליקון׃

יא האשימם אלקים יפלו ממעצותיהם;

ברב פשעיהם הדיחמו כי מרו בך׃

And so it ends with שמחה:

יב וישמחו כל חוסי בך לעולם ירננו ותסך עלימו;

ויעלצו בך אהבי שמך׃

יג כי אתה תברך צדיק; ה׳ כצנה רצון תעטרנו׃

And that is what I am calling a למנצח מזמור: Don’t worry, be happy. ה׳ will take care of your enemies.

פרק סד is very similar to פרק ה.

אין במזמורי תהלים שבלונה, אין נוסחאות נדושות, יש רגש מתחדש, גם כשהנושא ישן. לכאורה לפנינו עוד הפעם תפילה לה׳, בקשת ישועה. הבקשה היא שוב ושוב הצלה מיד אויב, מיד רשע, נושא שכבר פגשנוהו במזמורים אין מספר, ואעפי״כ אנו שומעים שוב הבעה חדשה, הסברה חדשה, אף רעיונות חדשים.

The רעיון חדש here is the emphasis on the sin of the enemy. Rashi, citing מדרש תהילים, says this perek is foreseeing Daniel in the lion’s den, after he was slandered by the other Persian satraps. Sforno says it is foreseeing Haman’s slander against the Jews. This perek is about לשון הרע.

א למנצח מזמור לדוד׃

ב שמע אלקים קולי בשיחי; מפחד אויב תצר חיי׃

As a תפילה, it makes a point that sometimes we cannot do a good job of praying, especially when we need to pray:

ופירש הרב החסיד מהר״ר יוסף יעבץ ז״ל בפירושו, לפי ששמיעת התפלה תלויה בכונת הלב באומרו (תהלים י:יז) תָּכִין לִבָּם תַּקְשִׁיב אָזְנֶךָ, ואולי מפחדו לא יוכל לכוין כראוי אמר ”שמע אלקים קולי בשיחי“.

ג תסתירני מסוד מרעים; מרגשת פעלי און׃

ד אשר שננו כחרב לשונם; דרכו חצם דבר מר׃

סוד here doesn’t mean “secret”; it mean “council”, as in קדושה:

נַעֲרִיצְךָ וְנַקְדִישְׁךָ כְּסוֹד שיחַ שרְפֵי קדֶשׁ הַמַּקְדִּישִׁים שִׁמְךָ בַּקּדֶשׁ…

But is still has the sense of “secret”, so סוד מרעים means “the conspiracy of those planning evil”. David may have had external enemies, but the internal ones were the most dangerous. We know that every nation had its favorite sin:

בתחילה הלך אצל בני עשו ואמר להם: מקבלים אתם את התורה? אמרו לו: מה כתוב בה? אמר להם לא תרצח. אמרו: רבש״ע, כל עצמו של אותו אביהם רוצח הוא…הלך לו אצל בני עמון ומואב ואמר להם: מקבלים אתם את התורה? אמרו לו: מה כתוב בו? אמר להם לא תנאף. אמרו לפניו: רבש״ע, עצמה של ערוה להם היא…הלך ומצא בני ישמעאל, אמר להם: מקבלים אתם את התורה? אמרו לו: מה כתוב בה? אמר להם לא תגנוב. אמרו לפניו: רבש״ע, כל עצמו אביהם לסטים היה…לא היתה אומה באומות שלא הלך ודבר, ודפק על פתחם מה ירצו ויקבלו את התורה…עד שפרקום ונתנום לישראל.

I can’t remember where I heard an interpretation of this Sifrei. We received the Torah because we didn’t ask, מה כתוב בה?; we said נעשה ונשמע. If we had asked, ה׳ would have told us: לא תלך רכיל בעמיך; don’t say לשון הרע. And we would have responded, כל עצמו אביהם מלשינים היה. That is our own special עברה.

David uses the metaphor of a sniper, firing arrows from hiding.

ה לִירֹת במסתרים תם; פתאם יֹרֻהוּ ולא יִירָאוּ׃

ו יחזקו למו דבר רע יספרו לטמון מוקשים;

אמרו מי יִרְאֶה למו׃

ז יחפשו עולת תמנו חפש מחפש;

וקרב איש ולב עמק׃

There’s a pun here (or perhaps it went with the melody) with ירה (shoot), ירא (fear) and ראה (see). They are getting things all confused; they should be seeing and fearing, not shooting. And the consequence is that ה׳ will shoot, and everyone will see and fear:

ח וַיֹּרֵם אלקים; חץ פתאום היו מכותם׃

ט ויכשילוהו עלימו לשונם; יתנדדו כל רֹאֵה בם׃

י וַיִּירְאוּ כל אדם; ויגידו פעל אלקים; ומעשהו השכילו׃

And we end as in פרק ה: the צדיק rejoices as the רשע isn’t so much punished as has to deal with the consequences of their own actions.: וַיַּכְשִׁילוּהוּ עָלֵימוֹ לְשׁוֹנָם.

ישמח צדיק בה׳ וחסה בו; ויתהללו כל ישרי לב׃

The next למנצח מזמור isn’t about reward and punishment, but simply about the glory of הקב״ה and what that means for human beings.

א למנצח על הגתית מזמור לדוד׃

ב ה׳ אדנינו מה אדיר שמך בכל הארץ;

אשר תנה הודך על השמים׃

There is an inclusio here: the last pasuk is also ה׳ אדנינו; מה אדיר שמך בכל הארץ. So we would expect that the perek would be about ה׳'s אדירות. And it sort of starts that way:

ג מפי עוללים וינקים יסדת עז;

למען צורריך; להשבית אויב ומתנקם׃

ד כי אראה שמיך מעשה אצבעתיך

ירח וכוכבים אשר כוננתה׃

“Out of the mouths of babes”. The sense here is that we need to just stop and look at the universe—כי אראה שמיך מעשה אצבעתיך—to achieve יראת ה׳.

א הא־ל הנכבד והנורא הזה—מצוה לאוהבו וליראה ממנו…והיאך היא הדרך לאהבתו, ויראתו: בשעה שיתבונן האדם במעשיו וברואיו הנפלאים הגדולים, ויראה מהם חכמתו שאין לה ערך ולא קץ—מיד הוא אוהב ומשבח ומפאר ומתאווה תאווה גדולה לידע השם הגדול, כמו שאמר דויד (תהילים מב:ג) צָמְאָה נַפְשִׁי לֵאלֹקִים לְאֵ־ל חָי.

ב וכשמחשב בדברים האלו עצמן, מיד הוא נרתע לאחוריו, ויירא ויפחד ויידע שהוא בריה קטנה שפלה אפלה, עומד בדעת קלה מעוטה לפני תמים דעות, כמו שאמר דויד (תהילים ח:ד) כִּי אֶרְאֶה שָׁמֶיךָ [מַעֲשֵׂה אֶצְבְּעֹתֶיךָ יָרֵחַ וְכוֹכָבִים אֲשֶׁר כּוֹנָנְתָּה].

But we can’t stop and look. As adults, we already “know” everything and never stop to think. We need to return to a “beginner’s mind”.

Often, adults learn so much that they lose the ability to unlearn, becoming poor at questioning things correctly. On the other hand, children are tuned to learn, which gives them some amazing advantages over adults. While children are designed to explore, to learn, to change, adults are designed to exploit, find resources, and make things happen. Adults have the capacity to learn, but children are in a constant state of extracting as much information from the world as possible. As a result, they are great at generalizing, adapting to challenges, and developing resilience.

But then the perek changes to focus on human beings:

ה מה אנוש כי תזכרנו; ובן אדם כי תפקדנו׃

ו ותחסרהו מעט מאלקים; וכבוד והדר תעטרהו׃

ז תמשילהו במעשי ידיך; כל שתה תחת רגליו׃

ח צנה ואלפים כלם; וגם בהמות שדי׃

ט צפור שמים ודגי הים; עבר ארחות ימים׃

יראת ה׳ should lead to a sense that we are insignificant compared with הקב״ה, but we are certainly not insignificant.

כז ויברא אלקים את האדם בצלמו בצלם אלקים ברא אתו; זכר ונקבה ברא אתם׃ כח ויברך אתם אלקים ויאמר להם אלקים פרו ורבו ומלאו את הארץ וכבשה; ורדו בדגת הים ובעוף השמים ובכל חיה הרמשת על הארץ׃

נעשה אדם בצלמנו: הצלם האלוקי הוא הבחירה, בלי טבע מכריח, רק מרצון ושכל חפשי…אנו יודעים שהבחירה החופשית הוא מצמצום האלוקות, שהשי״ת מניח מקום לברואיו לעשות כפי מה שיבחרו.

The message is that we need to be partners with ה׳ in creation.

הכרה זו עצמה מביאה את האדם שנברא בצלם אלוקים—וַתְּחַסְּרֵהוּ מְּעַט מֵאֱלוֹקִים, להתבונן בבריאה, לא רק כצופה מן הצד האוהב וחרד כאחד, ”ממעשיו וברואיו הנפלאים והגדולים“ של ה׳ יתברך. אלא גם כמי שהופקד על הבריאה להנהיגה ולשכללה, כשותף פעיל לריבונו של עולם. מנקודת מבט זו הופכת אהבת ה׳ ויראתו מתחושה פסיבית למחויבות אקטיבית הקוראת לאדם.

And when David ends with the same pasuk he starts with,

ה׳ אדנינו; מה אדיר שמך בכל הארץ׃

there is a new message. כי אראה שמיך מעשה אצבעתיך…תמשילהו במעשי ידיך. I see the wonders You have created and realize that you have put me in charge. With great power comes great responsibility.