I’m going to start with looking at the section of ספר תהילים that we usually call “הלל”, תהילים קיג-קיח. Much of what I’m going to say comes from Rabbi Yitzchak Etshalom and his essays on Hallel that was presented as part of his Mikra series for torah.org. As far as I can tell, only the first two (I, II) are available on the site; he was kind enough to email me the others. He says they will be available on yutorah.org “soon”. All errors and misinterpretations are, of course, mine.

The פרקי תהילים that we call “Hallel” is called in the halachic literature “הלל המצרי”, ”The Egyptian Hallel“. The first mention of that name is in the gemara:

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: אַקְרְיוּן הַלֵּלָא מִצְרָאָה בְּחֶלְמָא. אֲמַר לֵיהּ: נִיסֵּי מִתְרַחְשִׁי לָךְ.

הללא מצראה: הלל שאנו קורין בפסח לפי שיש הלל אחר הקרוי הלל הגדול קורין לזה הלל המצרי.

The gemara uses the term הלל הגדול for תהילים קלו:

מהיכן הלל הגדול? רבי יהודה אומר (תהלים קלו:א) מ”הודו“ עד (תהלים קלז:א) ”נהרות בבל“.

And we will look at that perek in detail (and why it gets to be “גדול”), so the תהילים we say every yom tov needs another name. Rashi explains that it is called הלל המצרי because we read it at the seder.

But that is still hard to understand, since we read הלל הגדול at the seder as well, and we read הלל המצרי on other holidays that are not connected to יציאת מצרים. Others propose that the name comes from תהילים קיד, בצאת ישראל ממצרים. But even that is hard to understand, since הלל הגדול mentions יציאת מצרים as well: למכה מצרים בבכוריהם…ויוצא ישראל מתוכם; כי לעולם חסדו.

So why הלל המצרי?

I think the answer lies in the gemara’s discussion of the origin of these פרקים:

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: שִׁיר שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה, מֹשֶׁה וְיִשְׂרָאֵל אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָלוּ מִן הַיָּם. וְהַלֵּל זֶה מִי אֲמָרוֹ? נְבִיאִים שֶׁבֵּינֵיהֶן תִּקְּנוּ לָהֶן לְיִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁיְּהוּ אוֹמְרִין אוֹתוֹ עַל כׇּל פֶּרֶק וּפֶרֶק, וְעַל כׇּל צָרָה וְצָרָה שֶׁלֹּא תָּבֹא עֲלֵיהֶן. וְלִכְשֶׁנִּגְאָלִין, אוֹמְרִים אוֹתוֹ עַל גְּאוּלָּתָן.

“הלל זה”, in the context here, is referring to what we call הלל. The gemara tells us it was composed by “נביאים שביניהן”:

כיון שמפורש בהו שירת אז ישיר לא נימא בהלל זה, דמשה וישראל אמרו; אלא נביאים שביניהן כו׳.

And we know that there were נביאים among בני ישראל beside Moshe:

ה ואמרת אליהם כה אמר אדנ־י ה׳ ביום בחרי בישראל ואשא ידי לזרע בית יעקב ואודע להם בארץ מצרים; ואשא ידי להם לאמר אני ה׳ אלקיכם׃ ו ביום ההוא נשאתי ידי להם להוציאם מארץ מצרים; אל ארץ אשר תרתי להם זבת חלב ודבש צבי היא לכל הארצות׃ ז ואמר אלהם איש שקוצי עיניו השליכו ובגלולי מצרים אל תטמאו; אני ה׳ אלקיכם׃

ואלו הנביאים שנתנבאו במצרים: (דברי הימים א ב:ו) וּבְנֵי זֶרַח זִמְרִי וְאֵיתָן וְהֵימָן וְכַלְכֹּל וָדָרַע כֻּלָּם חֲמִשָּׁה ומשה ואהרן.

The gemara objects: ספר תהילים was written by David!

הַלֵּל זֶה מִי אֲמָרוֹ? רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר, אֶלְעָזָר בְּנִי אוֹמֵר: מֹשֶׁה וְיִשְׂרָאֵל אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָלוּ מִן הַיָּם. וַחֲלוּקִין עָלָיו חֲבֵירָיו לוֹמַר שֶׁדָּוִד אֲמָרוֹ. וְנִרְאִין דְּבָרָיו מִדִּבְרֵיהֶן. אֶפְשָׁר יִשְׂרָאֵל שָׁחֲטוּ אֶת פִּסְחֵיהֶן וְנָטְלוּ לוּלְבֵיהֶן וְלֹא אָמְרוּ שִׁירָה?!

We cannot imagine all those centuries of celebrating יום טוב in the משכן without some sort of “Hallel”. The gemara goes on to list the historical times when Hallel must have been said:

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: הַלֵּל זֶה מִי אֲמָרוֹ? רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: מֹשֶׁה וְיִשְׂרָאֵל אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָמְדוּ עַל הַיָּם…

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: יְהוֹשֻׁעַ וְיִשְׂרָאֵל אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָמְדוּ עֲלֵיהֶן מַלְכֵי כְנַעַן…

רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר הַמּוֹדָעִי אוֹמֵר: דְּבוֹרָה וּבָרָק אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָמַד עֲלֵיהֶם סִיסְרָא…

רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן עֲזַרְיָה אוֹמֵר: חִזְקִיָּה וְסִייעָתוֹ אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָמַד עֲלֵיהֶם סַנְחֵרִיב…

רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: חֲנַנְיָה מִישָׁאֵל וַעֲזַרְיָה אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָמַד עֲלֵיהֶם נְבוּכַדְנֶצַּר הָרָשָׁע…

רַבִּי יוֹסֵי הַגְּלִילִי אוֹמֵר: מָרְדְּכַי וְאֶסְתֵּר אֲמָרוּהוּ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁעָמַד עֲלֵיהֶם הָמָן הָרָשָׁע…

חֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: נְבִיאִים שֶׁבֵּינֵיהֶן תִּיקְּנוּ לָהֶם לְיִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁיְּהוּ אוֹמְרִים אוֹתוֹ עַל כׇּל פֶּרֶק וּפֶרֶק וְעַל כׇּל צָרָה וְצָרָה שֶׁלֹּא תָּבֹא עֲלֵיהֶם לְיִשְׂרָאֵל. וְלִכְשֶׁנִּגְאָלִין, אוֹמְרִים אוֹתוֹ עַל גְּאוּלָּתָן.

Note the subtle distinction: there are two ways to recite Hallel: one, at the moment of a miraculous salvation (both at the time of the צרה and at the time of the גאולה). The second, when we remember those historical times (on יום טוב and the like). ואכמ״ל.

But what do we do with the idea that David wrote ספר תהילים, if Hallel was said from the time Israel left Egypt? And how could Israel, when leaving Egypt, sing about the splitting of the Jordan, the exclusive roles of בית אהרן and יהודה, the בית ה׳ in ירושלם? I think the answer is clear, but it is spelled out by the Ramban when he discusses the Rambam’s ספר המצוות. Rambam says that saying Hallel cannot be a מצוה דאורייתא,since it was written by David.

והפליאה שאמר הרב ז״ל והתבונן והתפלא היאך נחשוב שקריאת ההלל ששיבח בו דוד לא־ל שמשה רבינו צונו בה. וגם בעיני יפלא מאמר הרב שהוא עצמו ז״ל מנה במצות תפלה…והנה לדעתו צריך שנפרש ונאמר שנצטוו ישראל להתפלל אל הקב״ה…אבל שיתחייבו בכל יום בקר וערב זה תקנת חכמים…גם בתקנה זו לא פירשו מטבעה של תפלה אלא היו מתפללים כל אחד ואחד כפי צחות לשונו וחכמתו…ועזרא ובית דינו עמדו ותקנו י״ח ברכות כדי שיהיו ערוכות בפי הכל…והנה הרב למדנו הענין הזה וביאר אותו לנו ביאור שלם אם כן למה יתפלא על ההלל שנצטוה למשה בסיני שיאמרו ישראל שירה במועדיהם לא־ל שהוציאם ממצרים וקרע להם את הים והבדילם לעבודתו ובא דוד ותקן להם את ההלל הזה כדי שישירו בו.

So Ramban would say that there was an obligation to sing “Hallel”, but the text wasn’t defined. David wrote what we call “Hallel”, and established it (or it was established later) as the standard text for “Hallel”. But the gemara says “הַלֵּל זֶה”, which implies to my mind a specific text. So I would understand it like the Netziv:

והיינו דאיתא בפסחים דף קיז,א: כל התשבחות שבתהלים דוד אמרם, שנאמר (תהלים עב:כ) כָּלּוּ תְפִלּוֹת דָּוִד בֶּן יִשָׁי, והוא משום שדוד הגיה והוסיף בהם.

In other words, הַלֵּל זֶה is much older than David. There was some original text whose final form is in תהילים now. So we have something like the Documentary Hypothesis, but for תהילים, and we can try to piece together what was original and what was added over the centuries. But that will all be guesswork; we have no way of knowing.

But it does answer the question of why call it הלל המצרי: it is the הלל that was composed in its original form back in מצרים, before the Exodus. Ironically, this means that the pasuk בצאת ישראל ממצרים is a red herring; that is part of the text that is not מצרי.

The Netziv says that חז״ל understood this, that there were older “texts” that would be incorporated later into ספרי תנ״ך, and that can help us understand why the text we have is written the way it is:

ומזה באים כמה מדרשי אגדות לדרוש מקראות שאמר דוד וכדומה על עצמו בתפילתו, על דורות הקודמים, היינו משום שהיו מקובלים או הבינו בחכמתם דלפי הענין שנכתב אותו המקרא, לא היה ראוי להיכתב כך אלא באיזה דיוק לשון אחר. אלא משום שהיה מקובל לדוד וכדומה מכבר, ובשעה שיצא אותו מקרא לאור היה מדויק יפה לפי אותו ,ענין, והיה מקובל על פה. ובאו בדורות המאוחרים ואמרו וגם כתבו גם בענין שלפניהם באותו לשון המקובל מכבר. וכן מקרא (דברים ו:ד) ”שמע ישראל ה׳ א־לקינו ה׳ אחד“, ונתקשה בזה הרמב״ן אמאי לא כתיב ”ה׳ א־לקיך“ כמו לשון כל הפרשה. אבל מזה מבואר כדרשת חז״ל בפרק מקום שנהגו, שפסוק זה נאמר בימי יעקב ובניו לפני מותו. משום הכי כתוב בתורה באותו לשון עצמו שאמרו יעקב ובניו, ונכתב בתורה ”על פי ה׳ ביד משה“.

לא רק התוכן אלא גם הסגנון, כלומר מובאה מדויקת (אמנם לא כתובה עדיין בטכסט של תנ״ך). לאפוקי מתורה שבעל פה אשר התוכן בלבד היה ידוע…כאן מדובר אפוא, על נוסח של כתוב, שעדיין לא נכתב בספרי התנ״ך, אבל הנוסח המדויק היה קיים.

This is not really a radical idea, that the Jews had texts—whether written or orallly transmitted—that were not “holy enough” to be in the תורה or earlier books of נ״ך, but might have been incorporated in part or as a whole in later books.

It is the way I would look at הלל המצרי—the oldest text of a prayer that we have. Even though it is all praise of ה׳ for saving us, rather than a plea for future salvation, חז״ל said that it was said both עַל כׇּל צָרָה וְצָרָה and וְלִכְשֶׁנִּגְאָלִין, אוֹמְרִים אוֹתוֹ עַל גְּאוּלָּתָן. There is a concept of a “prophetic prayer”—we assume ה׳ will save us, and thank Him for his mercy even as we are begging for it. It’s an important theme in the יום כיפור davening, and is most obvious in Yonah’s prayer from inside the fish:

א וימן ה׳ דג גדול לבלע את יונה; ויהי יונה במעי הדג שלשה ימים ושלשה לילות׃ ב ויתפלל יונה אל ה׳ אלהיו ממעי הדגה׃ ג ויאמר קראתי מצרה לי אל ה׳ ויענני; מבטן שאול שועתי שמעת קולי׃…י ואני בקול תודה אזבחה לך אשר נדרתי אשלמה; ישועתה לה׳׃

The past tense here is the perfect: קראתי, not ואקרא. In a narrative text it would be “I had called and You had answered”. In a prayer, it is “I will have called and You will have saved us”. It is an expression of Yonah’s faith inה׳'s mercy. So too, in הלל we say מקימי מעפר דל; מאשפת ירים אביון even from the depths of the אשפת.

So let’s look at the structure of הלל. I assume everyone knows it well: there are 6 chapters, that clearly divide into 5 of הללויה and one of הודו לה׳, as we discussed last time. Two of the chapters we subdivide when we skip half of those chapters in “חצי הלל”, so we could look at הלל as having 8 sections.

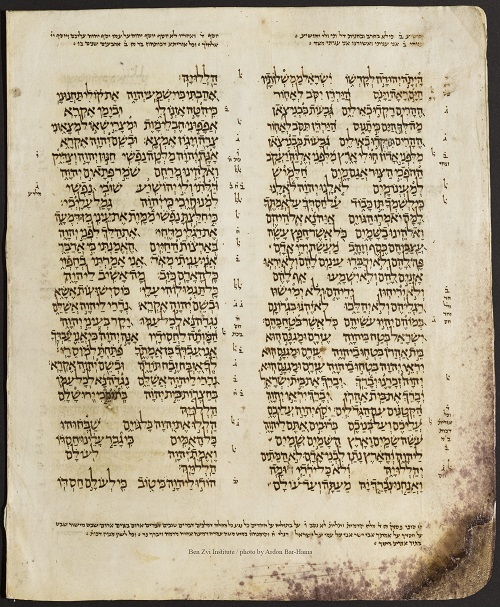

The 7 “הללויה” sections are divided by a הללויה between most of the chapters (as well as the inclusio at the beginning and the end), but there is no הללויה between קיד (בצאת ישראל) and קטו (לא לנו). And in fact, in the Aleppo Codex does not have a paragraph break between them:

So I would group those 7 sections not into 5 chapters, but into 4 parts: פרק קיג, then the combined פרקים קיד and קטו, then פרק קטז, and then the concluding 2 psukim of פרק קיז.

The first part, הללו עבדי ה׳; הללו את שם ה׳, is a general introduction; there is no specific event that the psalmist is praising ה׳ for. I would assume that מקימי מעפר דל is metaphoric, not referring to a particular דל or אביון.

The next part, בצאת ישראל ממצרים and לא לנו, are clearly fixed in history, with references to קריעת ים סוף (הים ראה וינס), מעמד הר סיני (ההרים רקדו כאילים), the wandering in the wilderness (ההפכי הצור אגם מים) and entering ארץ ישראל (הירדן תסב לאחור), and then move on to the general mission of בני ישראל to declare the glory of הקב״ה in the world (ואלקינו בשמים…ישראל, בְּטַח בה׳) and their reward (יברך את בית ישראל).

The next part is in first person. The Psalmist is talking about themself (אהבתי כי ישמע), what ה׳ has done for them and the obligation to somehow pay that back (מה אשיב לה׳ כל תגמולוהי עלי). It adds an aspect of הודאה to this section of הלל.

The next part is the shortest in תנ״ך, expressing exactly what הלל means (הללו את ה׳ כל גוים).

The next perek is the second part of הלל, the הודאה (הודו לה׳ כי טוב), that has its own introduction and conclusion.

So with that structure, I would propose that the ur-hallel, the הלל that נְבִיאִים שֶׁבֵּינֵיהֶן תִּקְּנוּ לָהֶן לְיִשְׂרָאֵל, was the introduction and concluding sections, with each generation inserting the שבח to ה׳ that was appropriate (and that our version has בצאת ישראל).

But in the eyes of חז״ל, there has to be more: I elided the quotes of the prooftexts in the gemara.

ת״ר: הלל זה מי אמרו?

ר״א אומר: משה וישראל אמרוהו בשעה שעמדו על הים; הם אמרו (תהלים קטוא) ”לא לנו ה׳ לא לנו“, משיבה רוח הקודש ואמרה להן (ישעיהו מח:יא) ”למעני למעני אעשה“.

רבי יהודה אומר: יהושע וישראל אמרוהו בשעה שעמדו עליהן מלכי כנען; הם אמרו ”לא לנו“ ומשיבה וכו׳.

רבי אלעזר המודעי אומר: דבורה וברק אמרוהו בשעה שעמד עליהם סיסרא; הם אמרו ”לא לנו“ ורוח הקודש משיבה ואומרת להם ”למעני למעני אעשה“.

ר׳ אלעזר בן עזריה אומר: חזקיה וסייעתו אמרוהו בשעה שעמד עליהם סנחריב; הם אמרו ”לא לנו“ ומשיבה וכו׳.

רבי עקיבא אומר: חנניה מישאל ועזריה אמרוהו בשעה שעמד עליהם נבוכדנצר הרשע; הם אמרו ”לא לנו“ ומשיבה וכו׳.

רבי יוסי הגלילי אומר: מרדכי ואסתר אמרוהו בשעה שעמד עליהם המן הרשע; הם אמרו ”לא לנו“ ומשיבה וכו׳.

וחכמים אומרים: נביאים שביניהן תיקנו להם לישראל שיהו אומרים אותו על כל פרק ופרק ועל כל צרה וצרה שלא תבא עליהם לישראל, ולכשנגאלין אומרים אותו על גאולתן

So, in my model, הלל that was תִּקְּנוּ לָהֶן לְיִשְׂרָאֵל was הללו את שם ה׳, then לא לנו ה׳ לא לנו; כי לשמך תן כבוד, then הללו את ה׳ כל גוים. David (as the compiler of ספר תהילים) puts them together, with his own בצאת ישראל and הודו לה׳, to create what we call הלל.

Evangelism— תהילים קיג and קיז, 10/17/2021

In the Image Of— תהילים קיד and קטו, 10/24/2021 and 11/14/2021

This Time It’s Personal— תהילים קטז, 11/21/2021 and 12/5/2021

Give Thanks Unto the L-rd Redux— תהילים קיח, 12/19/2021 and 1/9/2022