This week I want to look at the two women in Judah’s life:

א ויהי בעת ההוא וירד יהודה מאת אחיו; ויט עד איש עדלמי ושמו חירה׃

ב וירא שם יהודה בת איש כנעני ושמו שוע; ויקחה ויבא אליה׃

ג ותהר ותלד בן; ויקרא את שמו ער׃

ד ותהר עוד ותלד בן; ותקרא את שמו אונן׃

ה ותסף עוד ותלד בן ותקרא את שמו שלה; והיה בכזיב בלדתה אתו׃

ו ויקח יהודה אשה לער בכורו; ושמה תמר׃

First, who did he marry? A בת איש כנעני, but that may not mean what we think it means:

כנעני: תגרא.

וכנעני מנלן דאיקרי תגר? דכתיב ”וירא שם יהודה בת איש כנעני“. מאי כנעני? אילימא כנעני ממש—אפשר בא אברהם והזהיר את יצחק, בא יצחק והזהיר את יעקב, ויהודה אזיל ונסיב? אלא אמר רבי שמעון בן לקיש: בת גברא תגרא, דכתיב ”כנען בידו מאזני מרמה“, ואיבעית אימא מהכא ”אשר סחריה שרים כנעניה נכבדי ארץ“.

Note the two prooftexts; the first associates the Canaanites with unethical business practices:

כְּנַעַן בְּיָדוֹ מֹאזְנֵי מִרְמָה לַעֲשֹׁק אָהֵב׃

The second is neutral; כנעני is just a synonym for סוחר:

א מַשָּׂא צֹר; הֵילִילוּ אֳנִיּוֹת תַּרְשִׁישׁ כִּי שֻׁדַּד מִבַּיִת מִבּוֹא מֵאֶרֶץ כִּתִּים נִגְלָה לָמוֹ׃

…

ח מִי יָעַץ זֹאת עַל צֹר הַמַּעֲטִירָה אֲשֶׁר סֹחֲרֶיהָ שָׂרִים כִּנְעָנֶיהָ נִכְבַּדֵּי אָרֶץ׃

In English we have lots of words that come from ethnic stereotypes (mostly negative). This is the only one I know in תנ״ך, but it clearly is meant that way. כנעני means “peddler”, even about Jews:

וְגָלֻת הַחֵל הַזֶּה לִבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר כְּנַעֲנִים עַד צָרְפַת וְגָלֻת יְרוּשָׁלִַם אֲשֶׁר בִּסְפָרַד יִרְשׁוּ אֵת עָרֵי הַנֶּגֶב׃

But this use only shows up in תנ״ך after the Canaanites were defeated as a nation, in ספר שופטים. The gemara argues that this use of כנעני has to mean peddler since “obviously” Judah wouldn’t marry a real Canaanite! But that is a matter of dispute:

ר׳ יהודה אומר לאחיותיהם נשאו השבטים הה״ד (בראשית לז:לה) ”ויקומו כל בניו וכל בנתיו וגו׳“; ר׳ נחמיה אומר כנעניות היו.

Nonetheless, Ramban argues that this interpretation is correct in context:

ועל כל פנים זה האיש תגר, כי למה יצטרך הכתוב לאמר כי הוא כנעני ביחוסו, וכל אנשי הארץ ההיא כנענים הם…והראוי היה שיאמר ויקח שם יהודה אשה ושמה כך, כאשר הזכיר שמות הנשים בתמר ונשי עשו וזולתן (לעיל ד:יט, יא כט, כה:א).

אבל פירש בו שהוא תגר…וזה טעם ”וירא שם יהודה בת איש כנעני“, כי בעבור אביה נשאה…כי האיש ההוא יקרא להם הסוחר, כי הוא ידוע ומובהק בסחורתו אשר בעבורה גר שם.

But note that we don’t know her name. And it seems that Judah didn’t really know her either. When she dies, he sits shivah and goes straight back to work.

וירבו הימים ותמת בת שוע אשת יהודה; וינחם יהודה ויעל על גזזי צאנו הוא וחירה רעהו העדלמי תמנתה׃

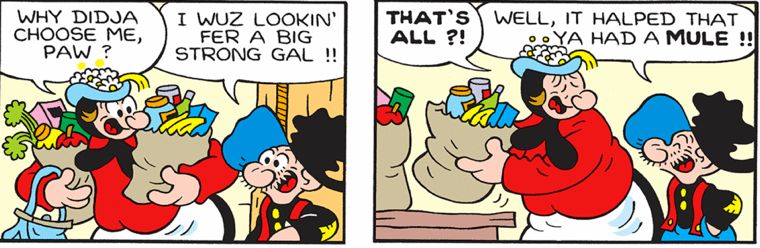

Speaking of primitive societies, Snuffy Smith is here to remind us that notions of romantic love are a luxury available only to the global elite. In most times and places, simple economic calculations are the primary factors in choosing a mate.

This was a practical marriage, made for his father-in-law’s business interests. It’s not wrong, per se, but Judah could do better. He was the leader of the שבטי י־ה, the ancestor of דוד המלך and משיח.

וירד יהודה וגו׳ וירא שם יהודה [בת איש כנעני ויקחה]. כיון שנטלה, אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא המשיח עתיד לעמוד מיהודה, והלך ונטל אשת כנענית, אלא מה אני עושה מביא עלילות, ומשיא לבנו את תמר, ותמר היתה בתו של שם הגדול, אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא תמות כנענית, שנאמר וירבו הימים וגומר ותמת בת שוע אשת יהודה (בראשית לח:יב), וימותו בניה, שנאמר וימת ער ואונן (בראשית מו), כדי שידבק יהודה בתמר, שהיא כהנת בתו של שם בן נח, שנאמר ומלכי צדק מלך וגו׳.

We get the sense that after the sale of Joseph, Judah gives up his leadership and just goes into business.

ויהי בעת ההוא: למה נסמכה פרשה זו לכאן, והפסיק בפרשתו של יוסף, ללמד שהורידוהו אחיו מגדולתו כשראו בצרת אביהם, אמרו אתה אמרת למכרו, אלו אמרת להשיבו היינו שומעים לך.

בת שוע was the perfect wife for Judah’s new role. I’m sure she was a fine woman. But ה׳ did not want his to give up his true role and so the story turns to Tamar.

Who was Tamar? We have only one hint initially, שמה תמר. But that says something:

הרשעים קודמים לשמם: נבל שמו, גלית שמו, שבע בן בכרי שמו. אבל הצדיקים שמן קודמם: ושמו אלקנה, ושמו ישי, ושמו בועז, ושמו מרדכי, ושמו מנוח, דומין לבוראן: ושמו ה׳. איתיבין ליה הכתיב (בראשית כד) ”ולרבקה אח ושמו לבן“! ר׳ יצחק אומר: אפורדוכסיס.

Rabbi Menachem Kasher understands this based on the midrash:

תני: שלשה שמות נקראו לאדם הזה: אחד שקראו לו אביו ואמו, ואחד שקראו לו אחרים, ואחד שקרוי לו בספר תולדות ברייתו.

הצדיקים שמן קודמן, היינו השם שקנו לעצמן על ידי מעשיהם הטובים והוא השם שנקראו בספר תולדות ברייתם הוא קודם לשם שקראו להם אבותיהם. מה שאין כן הרשאים שלא קנו לעצמם שם טוב נשארו רק בהשם שקראו להם אבותיהם.

[I have seen the opposite explanation cited in the name of the Michtav Me-Eliyahu.]

So we have a textual hint that she was a צדקת. She created her name with her actions. The midrash mentioned that she was בתו של שם הגדול. Where does that come from?

ויהי כמשלש חדשים ויגד ליהודה לאמר זנתה תמר כלתך וגם הנה הרה לזנונים; ויאמר יהודה הוציאוה ותשרף׃

ובת איש כהן כי תחל לזנות את אביה היא מחללת באש תשרף׃

ומלכי צדק מלך שלם הוציא לחם ויין; והוא כהן לא־ל עליון׃

ומלכי צדק: מדרש אגדה הוא שם בן נח.

ותשרף: אמר אפרים מקשאה משום רבי מאיר בתו של שם היתה, שהוא כהן, לפיכך דנוה בשרפה.

Ramban points out that this is not a halachic derivation, but a textual, midrashic one:

אני לא ידעתי הדין הזה, שבת כהן אינה חייבת שריפה אלא בזנות עם זיקת הבעל…אבל בת כהן שומרת יבם שזינתה אינה במיתה כלל, ובין בת ישראל ובין בת כהן אינה אלא בלאו גרידא…

ונראה לי שהיה יהודה קצין שוטר ומושל בארץ, והכלה אשר תזנה עליו איננה נדונת כמשפט שאר האנשים, אך כמבזה את המלכות, ועל כן כתוב ויאמר יהודה הוציאוה ותשרף, כי באו לפניו לעשות בה ככל אשר יצוה, והוא חייב אותה מיתה למעלת המלכות, ושפט אותה כמחללת את אביה לכבוד כהונתו, לא שיהיה דין הדיוטות כן.

Why does the midrash identify Tamar as the daughter of Shem? We have spoken before of the idea of “בית מדרשו של שם”:

”וישב אברהם אל נעריו“, ויצחק היכן הוא, רבי ברכיה בשם רבנן דתמן שלחו אצל שם ללמוד ממנו תורה.

כו ויאמר ברוך ה׳ אלקי שם; ויהי כנען עבד למו׃

כז יפת אלקים ליפת וישכן באהלי שם; ויהי כנען עבד למו׃

החכמים שהיו בהן…מדמין שאין שם א־לוה…אבל צור העולמים, לא היה שם מכירו ולא יודעו, אלא יחידים בעולם, כגון חנוך ומתושלח ונוח ושם ועבר. ועל דרך זו, היה העולם מתגלגל והולך, עד שנולד עמודו של עולם, שהוא אברהם אבינו עליו השלום.

Shem represents the “תורה” of בני נח, the idea that righteousness exists outside of the narrow confines of Jewish tradition. And that we see from Tamar’s actions:

כה הוא מוצאת והיא שלחה אל חמיה לאמר לאיש אשר אלה לו אנכי הרה; ותאמר הכר נא למי החתמת והפתילים והמטה האלה׃

כו ויכר יהודה ויאמר צדקה ממני כי על כן לא נתתיה לשלה בני; ולא יסף עוד לדעתה׃

(בראשית לח) והיא שלחה אל חמיה לאמר לאיש אשר אלה לו אנכי הרה. ותימא ליה מימר! אמר רב זוטרא בר טוביה ..נוח לו לאדם שיפיל עצמו לתוך כבשן האש ואל ילבין פני חבירו ברבים מנלן מתמר.

She was a model of חסד, of דרך ארץ. That is what it means to be a בתו של שם.

There’s another story we need to look at that is strikingly similar:

יד ותסר בגדי אלמנותה מעליה ותכס בצעיף ותתעלף ותשב בפתח עינים אשר על דרך תמנתה; כי ראתה כי גדל שלה והוא לא נתנה לו לאשה׃

טו ויראה יהודה ויחשבה לזונה; כי כסתה פניה׃

טז ויט אליה אל הדרך ויאמר הבה נא אבוא אליך כי לא ידע כי כלתו הוא; ותאמר מה תתן לי כי תבוא אלי׃

א ותאמר לה נעמי חמותה; בתי הלא אבקש לך מנוח אשר ייטב לך׃

ב ועתה הלא בעז מדעתנו אשר היית את נערותיו; הנה הוא זרה את גרן השערים הלילה׃

ג ורחצת וסכת ושמת שמלתך (שמלתיך) עליך וירדתי (וירדת) הגרן; אל תודעי לאיש עד כלתו לאכל ולשתות׃

ד ויהי בשכבו וידעת את המקום אשר ישכב שם ובאת וגלית מרגלתיו ושכבתי (ושכבת); והוא יגיד לך את אשר תעשין׃

…ז ויאכל בעז וישת וייטב לבו ויבא לשכב בקצה הערמה; ותבא בלט ותגל מרגלתיו ותשכב׃

ח ויהי בחצי הלילה ויחרד האיש וילפת; והנה אשה שכבת מרגלתיו׃

…יד ותשכב מרגלותו עד הבקר ותקם בטרום (בטרם) יכיר איש את רעהו; ויאמר אל יודע כי באה האשה הגרן׃

The parallel is impossible to ignore: we have a non-Jewish woman, widowed from a Jewish man, attempting a spiritual יבום with his relative. The man is unaware of what is going on as she engages in what we would judge as inappropriate actions to ensnare him. And in the end, she is vindicated and is the ancestor of מלכות:

יח ואלה תולדות פרץ פרץ הוליד את חצרון׃

יט וחצרון הוליד את רם ורם הוליד את עמינדב׃

כ ועמינדב הוליד את נחשון ונחשון הוליד את שלמה׃

כא ושלמון הוליד את בעז ובעז הוליד את עובד׃

כב ועבד הוליד את ישי וישי הוליד את דוד׃

ספר רות makes the connection between Ruth’s marriage and King David explicit. The aggadah sees the same connection in our parasha:

רבי שמואל בר נחמן פתח (ירמיה כט) ”כי אנכי ידעתי את המחשבות“. שבטים היו עסוקין במכירתו של יוסף, ויוסף היה עסוק בשקו ובתעניתו, ראובן היה עסוק בשקו ובתעניתו, ויעקב היה עסוק בשקו ובתעניתו, ויהודה היה עסוק ליקח לו אשה, והקב״ה היה עוסק בורא אורו של מלך המשיח, ”ויהי בעת ההיא וירד יהודה“, (ישעיה סו) ”בטרם תחיל ילדה“, קודם שלא נולד משעבד הראשון נולד גואל האחרון.

אמר ר׳ יוחנן:

בקש לעבור וזימן לו הקדוש ברוך הוא מלאך, שהוא ממונה על התאוה.

אמר לו: יהודה, היכן אתה הולך?

מהיכן מלכים עומדים?

מהיכן גדולים עומדים?

”ויט אליה אל הדרך“

בעל כורחו שלא בטובתו.

These apparently unseemly relationships are seen as integral to the Jewish monarchy. Why?

Much has been written about this question (see, for instance, Rabbi Moshe Eisemann’s Music Made in Heaven). But I think it’s really an optical illusion.

What Tamar and Ruth have in common is not only that they are not Jewish, but they are paradigms of חסד. There is a lesson there: חסד is not unique to the Jews or to the given Torah. It is what we call דרך ארץ:

רבי אלעזר בן עזריה אומר אם אין תורה אין דרך ארץ אם אין דרך ארץ אין תורה.

א״ר ישמעאל בר רב נחמן עשרים וששה דורות קדמה דרך ארץ את התורה׃ הה״ד (בראשית ג) לשמור את דרך עץ החיים דרך זו דרך ארץ ואח״כ עץ החיים זו תורה׃

The Maharal explains what דרך ארץ is:

…דרך ארץ, שהוא הנהגה שהוא ראוי לאדם, ואין בזה דברי מוסר שהם קשים על האדם רק הדרך שנוהגים בני אדם והם דרך חכמים, והם נקראים דרך ארץ. וכמו כל המסכתא של דרך ארץ שהוא ההנהגה הישרה והטובה….

ומזה נלמד כי דרך ארץ יסוד לתורה שהוא דרך עץ החיים, והוא ית׳ יתן חלקנו עם השומרים דרך עץ החיים.

אסור ליראת שמים שתדחק את המוסר הטבעי של האדם.

The illusion is in the fact that we only see the stories of two of the ancestors of מלכות. That’s the way תנ״ך works; if things are good, nothing is said.

מלכות without דרך ארץ is tyranny. Everyone, but especially a מלך, needs an עזר כנגדו that complements their strengths. There are 10 names in the list from יהודה until דוד. We only have the stories of two of their wives. I think that is because these are the two cases where things didn’t work out, and they needed the women (with Divine approval) to grab them by the throat and shake some sense into them.