Parashat Miketz almost always falls out during Chanukah, so we pretty much never read the designated haftorah for Miketz (going through my 200-year calendar, we read it 21 times in 200 years; the last time was in 2000 and the next time will be in 2020). But I just heard Rabbi David Fohrman’s lecture on this from the 2017 ימי עיון בתנ״ך, and I thought it was interesting enough to review. So let’s look at it.

The connection between the parasha and the haftorah is in the first pasuk:

ויקץ שלמה והנה חלום; ויבוא ירושלם ויעמד לפני ארון ברית אדני ויעל עלות ויעש שלמים ויעש משתה לכל עבדיו׃

ותבלענה השבלים הדקות את שבע השבלים הבריאות והמלאות; וייקץ פרעה והנה חלום׃

וייקץ והנה חלום means that it was a Dream with a capital D. And something must be done!

והנה חלום: והנה נשלם חלום שלם לפניו והוצרך לפותרים.

Similarly with Yaakov:

טז וייקץ יעקב משנתו ויאמר אכן יש ה׳ במקום הזה; ואנכי לא ידעתי׃

יז ויירא ויאמר מה נורא המקום הזה; אין זה כי אם בית אלקים וזה שער השמים׃

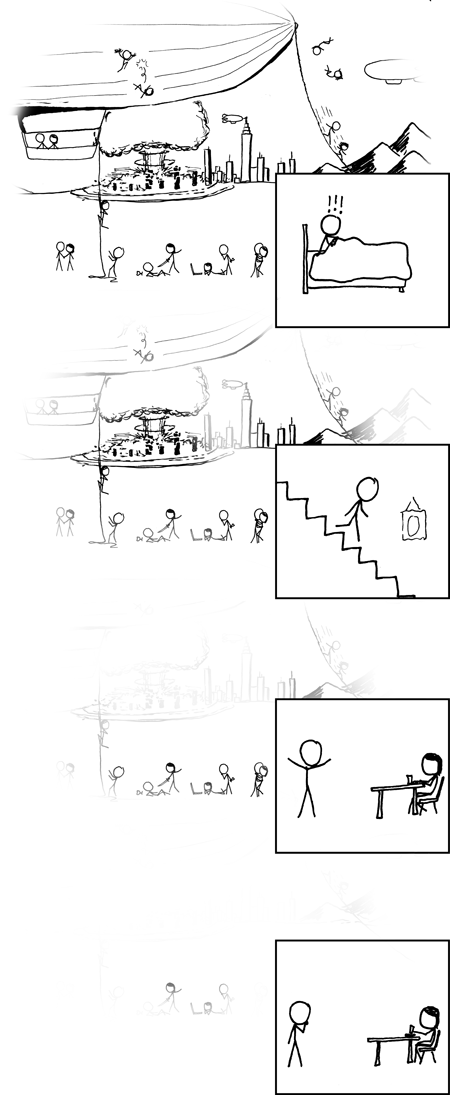

(from XKCD)

(from XKCD)

What was Shlomo’s dream? It’s not in the haftorah, but in the first half of the perek:

ה בגבעון נראה ה׳ אל שלמה בחלום הלילה; ויאמר אלקים שאל מה אתן לך׃

ו ויאמר שלמה אתה עשית עם עבדך דוד אבי חסד גדול כאשר הלך לפניך באמת ובצדקה ובישרת לבב עמך; ותשמר לו את החסד הגדול הזה ותתן לו בן ישב על כסאו כיום הזה׃

ז ועתה ה׳ אלקי אתה המלכת את עבדך תחת דוד אבי; ואנכי נער קטן לא אדע צאת ובא׃

ח ועבדך בתוך עמך אשר בחרת; עם רב אשר לא ימנה ולא יספר מרב׃

ט ונתת לעבדך לב שמע לשפט את עמך להבין בין טוב לרע; כי מי יוכל לשפט את עמך הכבד הזה׃

י וייטב הדבר בעיני א־דני; כי שאל שלמה את הדבר הזה׃

יא ויאמר אלקים אליו יען אשר שאלת את הדבר הזה ולא שאלת לך ימים רבים ולא שאלת לך עשר ולא שאלת נפש איביך; ושאלת לך הבין לשמע משפט׃

יב הנה עשיתי כדבריך; הנה נתתי לך לב חכם ונבון אשר כמוך לא היה לפניך ואחריך לא יקום כמוך׃

יג וגם אשר לא שאלת נתתי לך גם עשר גם כבוד; אשר לא היה כמוך איש במלכים כל ימיך׃

יד ואם תלך בדרכי לשמר חקי ומצותי כאשר הלך דויד אביך והארכתי את ימיך׃

So what does Shlomo do with his dream? It’s more that something is done to him. ה׳ sets up a situation where he can demonstrate his wisdom:

טז אז תבאנה שתים נשים זנות אל המלך; ותעמדנה לפניו׃

יז ותאמר האשה האחת בי אדני אני והאשה הזאת ישבת בבית אחד; ואלד עמה בבית׃

יח ויהי ביום השלישי ללדתי ותלד גם האשה הזאת; ואנחנו יחדו אין זר אתנו בבית זולתי שתים אנחנו בבית׃

יט וימת בן האשה הזאת לילה אשר שכבה עליו׃

כ ותקם בתוך הלילה ותקח את בני מאצלי ואמתך ישנה ותשכיבהו בחיקה; ואת בנה המת השכיבה בחיקי׃

כא ואקם בבקר להיניק את בני והנה מת; ואתבונן אליו בבקר והנה לא היה בני אשר ילדתי׃

כב ותאמר האשה האחרת לא כי בני החי ובנך המת וזאת אמרת לא כי בנך המת ובני החי; ותדברנה לפני המלך׃

כג ויאמר המלך זאת אמרת זה בני החי ובנך המת; וזאת אמרת לא כי בנך המת ובני החי׃

כד ויאמר המלך קחו לי חרב; ויבאו החרב לפני המלך׃

כה ויאמר המלך גזרו את הילד החי לשנים; ותנו את החצי לאחת ואת החצי לאחת׃

כו ותאמר האשה אשר בנה החי אל המלך כי נכמרו רחמיה על בנה ותאמר בי אדני תנו לה את הילוד החי והמת אל תמיתהו; וזאת אמרת גם לי גם לך לא יהיה גזרו׃

כז ויען המלך ויאמר תנו לה את הילוד החי והמת לא תמיתהו; היא אמו׃

כח וישמעו כל ישראל את המשפט אשר שפט המלך ויראו מפני המלך; כי ראו כי חכמת אלקים בקרבו לעשות משפט׃

The wisdom here is understanding human nature, לב שמע לשפט את עמך. A strictly just solution would in fact involve dividing the infant:

שניים אוחזין בטלית—זה אומר אני מצאתיה, וזה אומר אני מצאתיה, זה אומר כולה שלי, וזה אומר כולה שלי—זה יישבע שאין לו בה פחות מחצייה, וזה יישבע שאין לו בה פחות מחצייה, ויחלוקו.

(presumably with a joint custody agreement, not a sword)

Yossi and Yitzhak are on a train across Poland, each on his way to meet a prospective bride on the other side of the country. Halfway there, Yitzhak turns to Yossi and says, “Forget about this whole marriage thing. I just don’t like the idea.” So he gets off at the next stop and makes his way back home.

Meanwhile, Yossi continues on and is met at the final destination by the mothers of the two prospective brides. When the mothers realize what has happened, they instantly begin to fight over whose daughter should wed this precious little boychik. “He’s mine!” cries one. “Not on your life,” cries the other, “He will marry my daughter!”After bickering for a while, Yossi and the two mothers decide to go the rebbe and ask him to resolve the situation. In the grand tradition of the ancients, the rebbe replies, “Well, there is only one solution to this problem. Cut the boy in half, and you each take half home with you.”

At this, the first mother looks shocked, while the second mother grins and cries emphatically, “Yah! Cut him in half!!” The rebbe points to the second mother and says, “THAT is the real mother-in-law. Case closed.”

But Rabbi Fohrman says there’s something much deeper here. ה׳ is teaching Shlomo something about himself. Who was Shlomo? It goes back to David and Bat Sheva:

יג ויאמר דוד אל נתן חטאתי לה׳;

ויאמר נתן אל דוד גם ה׳ העביר חטאתך לא תמות׃

יד אפס כי נאץ נאצת את איבי ה׳ בדבר הזה; גם הבן הילוד לך מות ימות׃

טו וילך נתן אל ביתו; ויגף ה׳ את הילד אשר ילדה אשת אוריה לדוד ויאנש׃

טז ויבקש דוד את האלקים בעד הנער; ויצם דוד צום ובא ולן ושכב ארצה׃

יז ויקמו זקני ביתו עליו להקימו מן הארץ; ולא אבה ולא ברא אתם לחם׃

יח ויהי ביום השביעי וימת הילד; ויראו עבדי דוד להגיד לו כי מת הילד כי אמרו הנה בהיות הילד חי דברנו אליו ולא שמע בקולנו ואיך נאמר אליו מת הילד ועשה רעה׃

יט וירא דוד כי עבדיו מתלחשים ויבן דוד כי מת הילד; ויאמר דוד אל עבדיו המת הילד ויאמרו מת׃

כ ויקם דוד מהארץ וירחץ ויסך ויחלף שמלתו ויבא בית ה׳ וישתחו; ויבא אל ביתו וישאל וישימו לו לחם ויאכל׃

כא ויאמרו עבדיו אליו מה הדבר הזה אשר עשיתה; בעבור הילד חי צמת ותבך וכאשר מת הילד קמת ותאכל לחם׃

כב ויאמר בעוד הילד חי צמתי ואבכה; כי אמרתי מי יודע יחנני (וחנני) ה׳ וחי הילד׃

כג ועתה מת למה זה אני צם האוכל להשיבו עוד; אני הלך אליו והוא לא ישוב אלי׃

כד וינחם דוד את בת שבע אשתו ויבא אליה וישכב עמה; ותלד בן ויקרא (ותקרא) את שמו שלמה וה׳ אהבו׃

כה וישלח ביד נתן הנביא ויקרא את שמו ידידיה בעבור ה׳׃

Rabbi Fohrman notices the parallels to the נשים זנות story: there are two infants, one alive, one dead. There are two parents, David and Uriah. While the baby is biologically David’s (and David in fact tries to hide that by having Uriah sleep at home), the history of David’s family involves a lot of יבום, the idea that the child of a widow is the spiritual heir of her late husband. In this model, Shlomo is being metaphorically told that this very case came before הקב״ה: two parents with a claim to an infant. How should Bat Sheva’s child be divided?

There is precedent for this idea. We are familiar with the story of Naval and Avigail, and how David marries Avigail right after Naval dies. She has a son:

ב וילדו (ויולדו) לדוד בנים בחברון; ויהי בכורו אמנון לאחינעם היזרעאלת׃

ג ומשנהו כלאב לאביגל (לאביגיל) אשת נבל הכרמלי; והשלשי אבשלום בן מעכה בת תלמי מלך גשור׃

ד והרביעי אדניה בן חגית; והחמישי שפטיה בן אביטל׃

ה והששי יתרעם לעגלה אשת דוד; אלה ילדו לדוד בחברון׃

We see through ספר שמואל and ספר מלכים all the jockeying for power among David’s sons, but כלאב בן אביגיל never comes up. Rav Medan notes other oddities: his mother is called אשת נבל הכרמלי, even though נבל is dead. And he seems to be named after נבל:

ושם האיש נבל ושם אשתו אבגיל; והאשה טובת שכל ויפת תאר והאיש קשה ורע מעללים והוא כלבו (כָלִבִּי)׃

בבית דוד…תוסיף להיקרא ”אביגיל אשת נבל הכרמלי“. לבנה…תקרא כלאב…על

שם בעלה המת, הנצר העיקרי לבית כלב.

לדברינו אלה, כלאב הוא בן דוד הקם בייבום על שם נבל ועל נחלתו.

In this model, we are reading the famous משל of the poor man’s ewe incorrectly. The little lamb represents Uriah’s son. Uriah had no children; in a real sense, David took them away from him. So this baby, who is David’s biological child, should be (בראשית פרק לח:ט) לא לו יהיה הזרע.

א וישלח ה׳ את נתן אל דוד; ויבא אליו ויאמר לו שני אנשים היו בעיר אחת אחד עשיר ואחד ראש׃

ב לעשיר היה צאן ובקר הרבה מאד׃

ג ולרש אין כל כי אם כבשה אחת קטנה אשר קנה ויחיה ותגדל עמו ועם בניו יחדו; מפתו תאכל ומכסו תשתה ובחיקו תשכב ותהי לו כבת׃

ד ויבא הלך לאיש העשיר ויחמל לקחת מצאנו ומבקרו לעשות לארח הבא לו; ויקח את כבשת האיש הראש ויעשה לאיש הבא אליו׃

ה ויחר אף דוד באיש מאד; ויאמר אל נתן חי ה׳ כי בן מות האיש העשה זאת׃

ו ואת הכבשה ישלם ארבעתים; עקב אשר עשה את הדבר הזה ועל אשר לא חמל׃

The reason for את הכבשה ישלם ארבעתים is that is the appropriate punishment for sheep-stealing:

כי יגנב איש שור או שה וטבחו או מכרו חמשה בקר ישלם תחת השור וארבע צאן תחת השה׃

But how does that fit in David’s life? Rav Medan answers that he loses four children. He notes that בת שבע had 4 children before שלמה: the unnamed baby who died after a week and those named in דברי הימים:

ואלה נולדו לו בירושלים; שמעא ושובב ונתן ושלמה ארבעה לבת שוע בת עמיאל׃

אין לנו אלא הסבר אחד לכך: כשם שמת הילד הראשון, כך מתו גם שמוע, שובב

ונתן בילדותם. דוד ובת־שבע כאחד

משלמים את המחיר הנורא של ארבעת הבנים

תמורת הכבשה האחת.

What I’m going to say is a little different from the way Rabbi Fohrman presented it, but I think it represents an interesting way to look at the text.

When David prays for Bat Sheva’s baby, ויבקש דוד את האלקים בעד הנער, what is he praying for? He needs this baby:

ד ויהי בלילה ההוא;

ויהי דבר ה׳ אל נתן לאמר׃

ה לך ואמרת אל עבדי אל דוד

כה אמר ה׳; האתה תבנה לי בית לשבתי׃

ו כי לא ישבתי בבית למיום העלתי את בני ישראל ממצרים ועד היום הזה; ואהיה מתהלך באהל ובמשכן׃

…

יב כי ימלאו ימיך ושכבת את אבתיך והקימתי את זרעך אחריך אשר יצא ממעיך; והכינתי את ממלכתו׃

יג הוא יבנה בית לשמי; וכננתי את כסא ממלכתו עד עולם׃

יד אני אהיה לו לאב והוא יהיה לי לבן אשר בהעותו והכחתיו בשבט אנשים ובנגעי בני אדם׃

טו וחסדי לא יסור ממנו כאשר הסרתי מעם שאול אשר הסרתי מלפניך׃

טז ונאמן ביתך וממלכתך עד עולם לפניך; כסאך יהיה נכון עד עולם׃

The key phrase there is אשר יצא ממעיך, in the future. Not only will David not build the בית המקדש, but none of the children he has now will build it. This child represents his hope of a legacy, of a future. He can’t give it up. But after the sin of Uriah and Bat Sheva, נתן told him (שמואל ב יב:י) ועתה לא תסור חרב מביתך עד עולם. This, Rabbi Forhman says, is the meaning of (מלכים א ג:כד) ויאמר המלך קחו לי חרב. Both Uriah and David have a spiritual claim to the child. ה׳ says, OK, split him in half. But no child can survive that. It’s not in the text, but Rabbi Fohrman understands that for Shlomo, David realizes that he cannot be the father. He is willing to let the יבום stand and remove this son from his legacy (similar to the way we understood כלאב above). Then ה׳ says, now this child can be your legacy. But remember that he is not really yours; he is Mine: אני אהיה לו לאב והוא יהיה לי לבן. And so ה׳ gives him an additional name: וה׳ אהבו; וישלח ביד נתן הנביא ויקרא את שמו ידידיה בעבור ה׳.

With the incident of the two זנות, ה׳ gives Shlomo a glimpse of his own past and his own destiny, as it said in the dream: לא היה כמוך איש במלכים כל ימיך.