The next perek of פסוקי דזימרא is, in our model, based on the penultimate pasuk of אשרי:

שומר ה׳ את כל אהביו; ואת כל הרשעים ישמיד׃

Reading this, it seems inappropriate, far too violent for the poetic תהילים. And our perek is similarly problematic: חרב פיפיות בידם׃ לעשות נקמה בגוים; תוכחות בלאמים. It’s OK to praise ה׳ for saving us, but why celebrate destroying our enemies?

והא כתיב (דברי הימים ב כ:כא) בְּצֵאת לִפְנֵי הֶחָלוּץ וְאֹמְרִים הוֹדוּ לַה׳ כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ. וא״ר יוחנן: מפני מה לא נאמר כי טוב בהודאה זו? לפי שאין הקב״ה שמח במפלתן של רשעים. ואמר רבי יוחנן מאי דכתיב (שמות יד:כ) וְלֹא קָרַב זֶה אֶל זֶה כָּל הַלָּיְלָה? בקשו מלאכי השרת לומר שירה. אמר הקב״ה מעשה ידי טובעין בים ואתם אומרים שירה?

בִּנְפֹל אוֹיִבְךָ אַל תִּשְׂמָח; וּבִכָּשְׁלוֹ אַל יָגֵל לִבֶּךָ׃

But that seems to be exactly what we’re doing in our perek. In the sequence of פסוקי דזימרא, our הלל is becoming more ecstatic, with a שיר חדש and with musical instruments and dancing:

א הללויה;

שירו לה׳ שיר חדש; תהלתו בקהל חסידים׃

ב ישמח ישראל בעשיו; בני ציון יגילו במלכם׃

ג יהללו שמו במחול; בתף וכנור יזמרו לו׃

And we are singing to ה׳ because He has favored us and redeemed us:

ד כי רוצה ה׳ בעמו; יפאר ענוים בישועה׃

ה יעלזו חסידים בכבוד; ירננו על משכבותם׃

That’s all pretty standard. But then we describe what we’re celebrating, and it’s not even about G-d’s vengeance; it’s about ours. The חסידים are the ones with חרב פיפיות בידם:

ו רוממות א־ל בגרונם; וחרב פיפיות בידם׃

ז לעשות נקמה בגוים; תוכחות בלאמים׃

ח לאסר מלכיהם בזקים; ונכבדיהם בכבלי ברזל׃

ט לעשות בהם משפט כתוב הדר הוא לכל חסידיו;

הללויה׃

There are two approaches to this. One is to take it literally: our modern minds are too sensitive, but there are times that חסידים need to take up the sword.

אלי הולצר, חרב פיפיות בידם: אקטיביזם צבאי בהגותה של הציונות הדתית

אחד השינוים הדרמטיים ביותר בתולדות העם היהודי, בתודעתו הקולקטיבית ובזהותו העצמית מאז ימי מרד בר-כוכבא, הוא העובדה כי במציאות של מדינה יהודית, חלק ניכר ממנו נכון שוב לשאת נשק באופן מאורגן, לעשות שימוש בכוח צבאי וליטול חלק בניהול מלחמות…הספר שלפנינו בוחן את היחס של האקטיביזם הצבאי הלאומי כפי שהוא עולה מכתביהם של הוגים, רבנים ואנשי ציבור בציונות הדתית.

To understand the place of this אקטיביזם צבאי in ספר תהילים, I would like to cite C. S. Lewis, Orthodox Judaism’s favorite Anglican.

Cf. C. S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms (London, 1958), ch. 3, “The Cursings.” While written from an explicitly Christian point of view—and hence not wholly palatable for a Jewish reader—the chapter contains some valuable insights.

Reflections on the Psalms is Lewis’s essays on תהילים, and it is fascinating because it looks at תנ״ך through very different eyes than the ones we use, and makes us think about the assumptions that we take for granted. We talked about this in the context of “the sweetness of Torah” when discussing תהילים קיט. ”The Cursings“ is about the תהילים asking for נקמה, what Lewis calls “vindictiveness”.

[W]e cannot be certain that the comparative absence of vindictiveness…is a good symptom. This was borne in upon me during a night journey taken early in the Second World War in a compartment full of young soldiers. Their conversation made it clear that they totally disbelieved all that had read in the papers about the wholesale cruelties of the Nazi regime. They took it for granted…that this was all lies, all propaganda put out by our government to “pep up” our troops. And the shattering thing was, that, believing this, they expressed not the slightest anger. That our rulers should falsely attribute the worst of crimes to some of their fellow-men in order to induce other men to shed their blood seemed to them a matter of course…Now it seemed to me that the most violent of the Psalms—or, for that matter any child wailing out “But it’s not fair”—was in a more hopeful condition than these young men…[N]ot to perceive [the diabolical wickedness] at all—not even to be tempted to resentment—to accept it as the most ordinary thing in the world—argues a terrifying insensibility. Clearly these young men had…no conception of good and evil whatsoever.

Thus the absence of anger…can, in my opinion, be a most alarming symptom.

The expression חרב פיפיות, a “double-edged sword” may be a hint to this. Righteous anger is a dangerous thing.

Even when that indignation passes into bitter personal vindictiveness, it may still be a good symptom, though bad in itself. It is a sin; but at least it shows that those who commit it have not sunk below the level at which the temptation to that sin exists…If the Jews cursed more bitterly than the Pagans this was, I think, at least in part because they took right and wrong more seriously…Different, certainly higher, a better symptom; yet also leading to a more terrible sin. For it encourages a man to think that his own worse passions are holy.

So the חרב פיפיות must always be preceded by רוממות א־ל בגרונם; it has to be not just in the service of G-d, but reflecting the will of G-d.

שיר חדש is usually taken as a reference to אחרית הימים, when ה׳'s justice will be made manifest.

כל השירות שנאמרו בעולם לשון נקבות…אבל לעתיד לבא…אומרים שיר, לשון זכר שנאמר (תהלים צו) שירו לה׳ שיר חדש.

I don’t want to get too mystical, but the later Kabbalists were sensitive to the nuances of the language of תהילים and used that language to describe their elaborate mystical systems. It’s important to note that “masculine” and “feminine” here have nothing to do with real men and women; men are not more “masculine” and women not more “feminine”. חסד is masculine, דין is feminine. It is using biology as a metaphor for other concepts, like the terms ”male“ and “female” for pipes or electrical connections.

…In terms of our שיר, masculine is the infinite potential of the עתיד לבא. Feminine is the limited reality we live in now. A song of the potential future is a שיר. This is the song of ביאת משיח, the end of history. ה׳ will be the acknowledged ruler of all humanity and we will live in a perfectly just society.

And we will be an active part of that eschatological battle, and will celebrate the ultimate victory of good.

רוממות א־ל: כשיבואו למלחמה עם גוג מגוג כך ירוממו הא־ל כי שהוציאם מן הגלות, והתפלה תהיה בפיהם וחרב בידם.

That works for our perek. But it seems out of context. This is part of the הלל of everyday. It clearly follows from the last perek, which ended with תהלה לכל חסידיו, leading to our תהלתו בקהל חסידים. We’ve argued that פסוקי דזימרא is the הלל of ה׳'s פרנסה, sustaining the world both physically (חלב חטים ישביעך) and emotionally (מעודד ענוים ה׳). This isn’t the place “to vanquish your enemies, to chase them before you, to rob them of their wealth, to see those dear to them bathed in tears” (Genghis Khan). So, at least as part of our תפילה, I would read this perek allegorically.

The allegory comes from חז״ל.

וַאֲנִי נָתַתִּי לְךָ שְׁכֶם אַחַד עַל אַחֶיךָ; אֲשֶׁר לָקַחְתִּי מִיַּד הָאֱמֹרִי בְּחַרְבִּי וּבְקַשְׁתִּי׃

ואומר ”ואני נתתי לך שכם אחד על אחיך אשר לקחתי מיד האמורי בחרבי ובקשתי“ וכי בחרבו ובקשתו לקח? והלא כבר נאמר (תהילים מד:ז) כִּי לֹא בְקַשְׁתִּי אֶבְטָח וְחַרְבִּי לֹא תוֹשִׁיעֵנִי? אלא חרבי זו תפלה, קשתי זו בקשה.

And this particular חרב is a particular תפלה:

אמר רבי יצחק: כל הקורא קריאת שמע על מטתו, כאלו אוחז חרב של שתי פיות בידו. שנאמר: רוֹמְמוֹת אֵ־ל בִּגְרוֹנָם וְחֶרֶב פִּיפִיּוֹת בְּיָדָם, מאי משמע? אמר מר זוטרא ואיתימא רב אשי: מרישא דענינא, דכתיב: יַעְלְזוּ חֲסִידִים בְּכָבוֹד יְרַנְּנוּ עַל מִשְׁכְּבוֹתָם. וכתיב בתריה: רוֹמְמוֹת אֵ־ל בִּגְרוֹנָם וְחֶרֶב פִּיפִיּוֹת בְּיָדָם.

האדם הוא מורכב, חמרי ושכלי. מצד כח השכלי שבו הוא רב אונים להתייצב נגד כל הכוחות הרעים, אבל מצד החלק החמרי שבו הוא עלול לפול ברשת תחת יד שונאי נפשו המה הכוחות הרעים. ע״כ הוא משול שיש בידו חרב שלה אך פה אחד, מצד השכלי, ולא מצד החמרי. והנה כשהאדם ישן, נשאר חלק החמרי לבדו וחלק השכלי מסתלק ממנו. ע״כ רוח הטומאה שורה עליו, ויכול התחזקות כח החמרי לגרום לו תכונה רעה בשעת השינה, גם אחרי העירו. ע״כ מסרו לנו חז״ל סגולת ק״ש שעל המטה, שעל ידה יקנה הכח החמרי שבו רושם קדושה, גדול מהכח השכלי שבו, עד שמצד עצמו לא ימוט רגליו וילחם נגד הכוחות הרעים. ע״כ הוא נמשל ע״י ק״ש שעל מטתו, כאוחז חרב של ב׳ פיות, שבין מצד השכלי בין מצד החמרי, הוא גבור ומזויין שעל אויביו יתגבר.

My reading: the חרב פיפיות בידם is our תפלה that defends and integrates the two halves of our selves, what Rav Kook calls חמרי ושכלי. More philosophical authors would call them חומר and צורה, matter and form. The לאמים that require תוכחה are all the myriad parts of us that need to be tied together, לאסר מלכיהם בזקים; ונכבדיהם בכבלי ברזל.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

And that is the next aspect of ה׳'s פרנסה that we celebrate. I go to sleep every night and I awaken every morning, and I am still me. That re-integration of my multitudes is the greatest miracle of all.

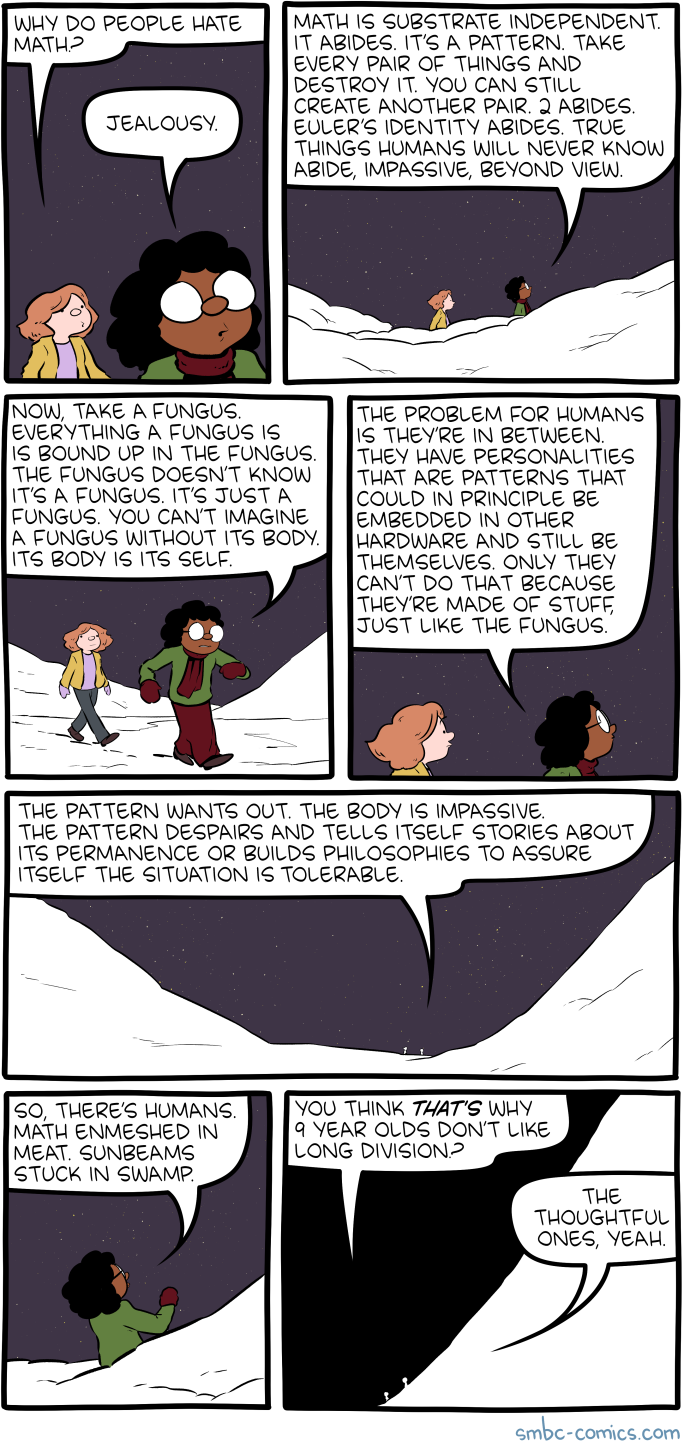

Humans are math enmeshed in meat. You can despair over that, or praise your Creator for making that possible.

Rav Hutner brings up an obscure halachic point: a bracha never ends with two thoughts. If we wish to express two concepts, we make two brachot:

רבי אומר: אין חותמין בשתים.

But the bracha of אשר יצר seems to violate this rule:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה׳, רוֹפֵא כָל בָּשָׂר וּמַפְלִיא לַעֲשׂוֹת.

The bracha is about the miracle of the physical body (Dr. Kenneth Prager wrote an essay in JAMA that everyone should read, about אשר יצר), and the מַפְלִיא לַעֲשׂוֹת would seem to be part of that. However, Rav Hutner cites the Rema, that מַפְלִיא לַעֲשׂוֹת isn’t really the end of the bracha, it’s a bridge to the next bracha, אלוקי נשמה שנתת בי:

הגה: יש לפרש שמפליא לעשות במה ששומר רוח האדם בקרבו, וקושר דבר רוחני בדבר גשמי.

גוף הברכה של אשר יצר נוסד על עניינים של הנפש הטבעית…ומצד זה היא מסתיימת מהחתימה של רופא כל בשר. אלא שניתוסף על חתימה זו גם הענין של ומפליא לעשות, מפני שאחרי ברכה זו של אשר יצר באה הוא הברכה של אלקי נשמה…ולכן באים המלים הללו של ומפליא לעשות בתור קשר-גשר של שתי הברכות הללו.

That’s why this requires שירו לה׳ שיר חדש. Every day is worth a new song.

שירו לה׳ שיר חדש: כלומר לא יהיה להם די בשירים האלה הכתובים אלא הם יחדשו לו שיר.

And the way to integrate them is לעשות בהם משפט כתוב, to keep the Torah that is a הדר הוא לכל חסידיו.

And so we conclude with the last pasuk of אשרי:

תהלת ה׳ ידבר פי; ויברך כל בשר שם קדשו לעולם ועד׃

with a perek that ironically doesn’t praise ה׳ at all. It’s a statement of how to praise ה׳, not what to say:

א הללויה;

הללו א־ל בקדשו; הללוהו ברקיע עזו׃

ב הללוהו בגבורתיו; הללוהו כרב גדלו׃

ג הללוהו בתקע שופר; הללוהו בנבל וכנור׃

ד הללוהו בתף ומחול; הללוהו במנים ועגב׃

ה הללוהו בצלצלי שמע; הללוהו בצלצלי תרועה׃

ו כל הנשמה תהלל י־ה; הללויה׃

It starts with the parallel that we saw in פרק קמח: human beings singing בקדשו, in the בית המקדש; and the hosts of heaven singing ברקיע עזו. Rav Schwab (in Rav Schwab on Prayer, p. 209) says that this isn’t really limited to the בית המקדש, because our goal is that the entire world should become מקום קדשו:

כתיב (ישעיהו סו:כג) וְהָיָה מִדֵּי חֹדֶשׁ בְּחָדְשׁוֹ [וּמִדֵּי שַׁבָּת בְּשַׁבַּתּוֹ יָבוֹא כָל בָּשָׂר לְהִשְׁתַּחֲוֹת לְפָנַי אָמַר ה׳], והיאך אפשר שיבא כל בשר בירושלים בכל שבת ובכל חדש? אמר רבי לוי: עתידה ירושלים להיות כארץ ישראל וארץ ישראל ככל העולם כלו.

And both are wordless.

ב השמים מספרים כבוד א־ל; ומעשה ידיו מגיד הרקיע׃

…ד אין אמר ואין דברים; בלי נשמע קולם׃

אין כאן התבוננות בטבע, ולא בהיסטוריה, אין כאן סליחות ותחנונים, אין כאן נקמה בגויים, ולא עמידה מול רשעים, לא מאבק נגדם עם ציפייה לישועת ה׳, ולא התמודדות עם ”הצלחותיהם“ עד יבוא יומם וגמולם מיד ה׳—כל אלה מילאו וגדשו את מזמורי תהילים, וגם במזמורי ”הַלְלוּ יָ־הּ“ מצאנו אותם; הגיע העת להתרומם מכל אלה אל הלל נקי.

We then praiseה׳ בגבורתיו and כרב גדלו. The latter preposition makes sense, כרב גדלו, ”in accordance with His greatness“. But the ב־ in בגבורתיו is odd. We translate בקדשו as “in His holy place”, and in the rest of the perek, בתקע שופר…בנבל וכנור, ב־ is instrumental, “with the blast of the shofar…with harp and lyre.”

You could translate בגבורתיו as “with His mighty acts”, meaning that our הלל will speak of ה׳'s גבורה. But that doesn’t go with the wordlessness of this perek. So I would translate it as “in the midst of His might”, standing in the middle of creation, where we experience רב גדלו.

When [the homo religiosus] confronts G-d’s world, when he gazes at the myriads of events and phenomena occuring in the cosmos, he does not desire to transform the secrets embedded in creation into simple equations…He gazes at that which is obscure without the intent of explaining it and inquires into that which is concealed without the intent of receiving the reward of clear understanding.

When he stands before the cosmos, he is entirely aflame with the holy fire of wonder…He is frightened—nay terrified—by the mystery…He flees from it, but at the same time, against his will, he draws near to it; enchanted, he finds himself irresitibly pulled toward it, pines for it, and longs to merge with it.

Our perek is how to do just that, and it starts with the shofar. We have talked about the shofar as the embodiment of wordless prayer:

ד תקעו בחדש שופר; בכסה ליום חגנו׃…ו…שפת לא ידעתי אשמע׃

“I, G-d, listen to the language of ‘לא ידעתי’, ‘I don’t know’.” The shofar is the language that has no words to express itself.

And finally comes the sound of the shofar…a wordless cry in a religion of words…And whether the shofar is our cry to G-d or G-d’s cry to us, somehow in that tekia, shevarim, terua — the call, the sob, the wail — is all the pathos of the Divine-human encounter as G-d asks us to take His gift, life itself, and make of it something holy by so acting as to honour G-d and His image on earth, humankind.

On Rosh Hashanah we are reminded that there are some things that remain outside the realm of human comprehension, but also, that we nevertheless are required to try and comprehend them…Part of our task here on earth is to translate the untranslatable cry of the shofar, even while we recognize how impossible that is.

We all know the story:

In a small town in Poland, there was an orphan shepherd boy who grew up knowing very little about being Jewish. One day, shortly before Yom Kippur, he met a group of people who were traveling to Mezibush to spend the holiday with the Baal Shem Tov. The boy decided to join them and soon, he was standing with the many people in the Baal Shem Tov’s shul.

But the boy did not know how to daven he couldn’t even read the Aleph-Beis. He saw all the people davening earnestly from the depths of their hearts, and he also wanted to say something to HaShem that came from deep inside. So he drew a deep breath and let out the shrill whistle that he would sound every evening when he gathered the sheep from the fields. Right in the middle of davening on Yom Kippur, the shepherd boy whistled as loud as he could.

The people in the shul were shocked, but the Baal Shem Tov calmed them and said, “A terrible decree was hanging over us. The shepherd boy’s whistle pierced the heavens and erased the decree. His whistle saved us, because it was sincere and came from the very bottom of his heart, where he feels love for HaShem even though he doesn’t know or understand why.”

Poetry is putting words to feelings that have no words. But we, unlike David, are not poets. Any words we try to use to express ourselves would be inadequate. But that is enough for כל הנשמה תהלל י־ה, for every living thing to praise ה׳, and for the entirety of our selves to praise ה׳. It’s not that הקב״ה needs our praise; it is that we need it.

The Psalmists in telling everyone to praise God are doing what all men do when they speak about what they care about…

I think we delight to praise what we enjoy because the praise not merely expresses but completes the enjoyment; it is its appointed consummation. It is not out of compliment that lovers keep on telling one another how beautiful they are; the delight is incomplete till it is expressed. It is frustrating to have discovered a new author and not to be able to tell anyone how good he is; to come suddenly, at the turn of the road, upon some mountain valley of unexpected grandeur and then to have to keep silent because the people with you care for it no more than for a tin can in the ditch; to hear a good joke and find no one to share it with.

Unlimited by words, the psalmist attempts to create a complete and seamless relationship between the author and the reader; both together prepare for the ultimate conclusion of this book of life. This is the שיר חדש—the “new song” alluded to in the previous psalm; this is the final praise which he yearns to be sung by all creatures who possess breath.

“All creatures who possess breath” is the usual translation of כל הנשמה תהלל י־ה. But I think it would be better to translate it as “all of one’s breath”. The word נשמה doesn’t appear anywhere else in ספר תהילים, and elsewhere in תנ״ך it clearly means “breath”, not the more modern meaning of “soul” (in תהילים that is called “כבוד”). It fits in with the “wordless” theme—I praise ה׳ simply by breathing.

רַבִּי לֵוִי בְּשֵׁם רַבִּי חֲנִינָא אָמַר: עַל כָּל נְשִׁימָה וּנְשִׁימָה שֶׁאָדָם נוֹשֵׁם צָרִיךְ לְקַלֵּס לַבּוֹרֵא, מַה טַּעַם (תהלים קנ:ו): כֹּל הַנְּשָׁמָה תְּהַלֵּל יָ־הּ; כָּל הַנְּשִׁימָה תְּהַלֵּל יָ־הּ.

And this ends ספר תהלים. But that doesn’t complete all possible תהלים.

אמר שלמה: אני לא אעשה כמו שעשה אבא, אבא פתח חכמתו בראש אותיות [אַשְׁרֵי הָאִישׁ] וסיים באמצע כֹּל הַנְּשָׁמָה, תְּהַלֵּל יָ־הּ, אבל אני איני עושה כן; אני פותח באמצע אותיות [מִשְׁלֵי שְׁלֹמֹה בֶן דָּוִד] ומסיים בסוף אותיות [תְּנוּ לָהּ מִפְּרִי יָדֶיהָ].

David ends his book halfway through the alphabet. Shlomo takes that as an invitiation to continue on in his own words, with his own feelings. And so should we all.

To summarize in Twitter-ish:

פסוקי דזימרא is the הלל sung:

קמו: in solitude קמז: with community קמח: with the universe קמט: with song and dance קנ: without words

פסוקי דזימרא is the הלל of:

קמו: the miracle of physical sustenance קמז: the miracle of emotional stability קמח: the miracle of being part of creation קמט: the miracle of spiritual integration קנ: the miracle of הלל

And so we conclude פסוקי דזימרא and are truly ready to start our תפילה.