The previous pasuk introduced Shlomo’s aim: לדעת חכמה ומוסר, to deeply understand, to integrate, ethics and the consequences of not acting ethically. He continues:

לקחת מוסר השכל; צדק ומשפט ומשרים׃

We’ve already talked about מוסר. What is מוסר השכל? Ibn Ezra says השכל is a separate thing; the pasuk means “to attain discipline and שכל—common sense”:

השכל: שם הפועל והוא חסר וי״ו.

But the מוסר part would be redundant, and there is no ו החיבור. So most commentators take השכל as an adjective:

לקחת מוסר השכל: יש מוסר, ויש מוסר השכל…והנה המוסר היוצא ע״י יראת ה׳ שיתיירא מענשו נקרא בשם מוסר סתם, והמוסר היוצא על ידי יראת הרוממות שמשיג גדולתו של השי״ת ויירא מרוממותו מעשות דבר נגד חקי החכמה אשר ישכילם בשכל טוב, זה נקרא מוסר השכל.

Malbim adds that שכל as used in ספר משלי is what we would call “intuition”; Kahneman’s “Thinking Fast”.

השכל הוא הכח שיש לאדם המשכיל לחדור בכל דבר בידיעה פתאומית ולשפוט על דברים שהם נעלמים מכח החכמה והבינה, וגם על דברים שאין לחוש מבוא בהם כמו ידיעת ה׳ והרוחנים וכדומה מדרושים שאחר הטבע.

מוסר is the awareness of the negative consequences of doing the wrong thing (contrasted to חכמה which is the awareness of the benefits of doing the right thing); מוסר השכל is when that becomes intuitive, part of what Jonathan Haidt calls “moral judgment” as opposed to “moral reasoning”. An important part of learning ספר משלי is to develop that moral intuition.

In Yeshivish parlance, מוסר השכל means a practical lesson, as opposed to theoretical—”What is the מוסר השכל of that story“. שכל in many places in תנ״ך doesn’t mean “sense”, it means “success”:

יד ויהי דוד לכל דרכו משכיל; וה׳ עמו׃ טו וירא שאול אשר הוא משכיל מאד; ויגר מפניו׃ טז וכל ישראל ויהודה אהב את דוד; כי הוא יוצא ובא לפניהם׃

For acquiring the discipline for success…

לקחת: התכלית הוא לקחת מוסר השכל, היינו שיצליח כמו שכתוב וַיְהִי דָוִד לְכׇל דְּרָכָו מַשְׂכִּיל.

משלי will teach you the מוסר you need to be successful in interpersonal relationships, which means צדק ומשפט ומשרים.

…Righteousness, justice, and equity.

Equity in the modern use means “equality of outcomes” but משרים really means “compromise, balance”:

ומשרים: היא הפשרה דרך חלק ומישור שוה לזה ולזה.

משרים is important because צדק and משפט are important, but they are mutually contradictory. מדת הרחמים and מדת הדין are a dialectic, in human behavior as much as in Jewish theology.

וימלך דוד על כל ישראל; ויהי דוד עשה משפט וצדקה לכל עמו׃

בדוד הוא אומר (שמואל ב ח) ”ויהי דוד עושה משפט וצדקה“ והלא כל מקום שיש משפט אין צדקה וצדקה אין משפט? אלא איזהו משפט שיש בו צדקה? הוי אומר זה ביצוע. אתאן לת״ק: דן את הדין, זיכה את הזכאי וחייב את החייב, וראה שנתחייב עני ממון, ושלם לו מתוך ביתו. זה משפט וצדקה: משפט לזה וצדקה לזה; משפט לזה שהחזיר לו ממון וצדקה לזה ששילם לו מתוך ביתו.

The idea of פשרה, compromise, is what it means to be ישר.

ועשית הישר והטוב בעיני ה׳; למען ייטב לך ובאת וירשת את הארץ הטבה אשר נשבע ה׳ לאבתיך׃

הישר והטוב. זו פשרה [ו]לפנים משורת הדין.

And it characterizes ה׳'s relationship with human beings:

ח נהרות ימחאו כף; יחד הרים ירננו׃ ט לפני ה׳ כי בא לשפט הארץ; ישפט תבל בצדק; ועמים במישרים׃

There are no simple answers. Ethics requires balance. And that is not just in court cases but in our own lives, in determining our own character. Every ethical decision we make is a compromise between competing values.

א דעות הרבה יש לכל אחד ואחד מבני אדם וזו משנה מזו…יש אדם שהוא בעל חמה כועס תמיד. ויש אדם שדעתו מישבת עליו ואינו כועס כלל ואם יכעס יכעס כעס מעט בכמה שנים. ויש אדם שהוא גבה לב ביותר. ויש שהוא שפל רוח ביותר. ויש שהוא בעל תאוה לא תשבע נפשו מהלך בתאוה. ויש שהוא בעל לב טהור מאד ולא יתאוה אפלו לדברים מעטים שהגוף צריך להן. ויש בעל נפש רחבה שלא תשבע נפשו מכל ממון העולם…ויש מקצר נפשו שדיו אפלו דבר מעט שלא יספיק לו ולא ירדף להשיג כל צרכו. ויש שהוא מסגף עצמו ברעב וקובץ על ידו ואינו אוכל פרוטה משלו אלא בצער גדול. ויש שהוא מאבד כל ממונו בידו לדעתו. ועל דרכים אלו שאר כל הדעות כגון מהולל ואונן וכילי ושוע ואכזרי ורחמן ורך לבב ואמיץ לב וכיוצא בהן…

ג שתי קצוות הרחוקות זו מזו שבכל דעה ודעה אינן דרך טובה ואין ראוי לו לאדם ללכת בהן ולא ללמדן לעצמו. ואם מצא טבעו נוטה לאחת מהן או מוכן לאחת מהן או שכבר למד אחת מהן ונהג בה יחזיר עצמו למוטב וילך בדרך הטובים והיא הדרך הישרה.

ד הדרך הישרה היא מדה בינונית שבכל דעה ודעה מכל הדעות שיש לו לאדם. והיא הדעה שהיא רחוקה משתי הקצוות רחוק שוה ואינה קרובה לא לזו ולא לזו. לפיכך צוו חכמים הראשונים שיהא אדם שם דעותיו תמיד ומשער אותם ומכון אותם בדרך האמצעית כדי שיהא שלם בגופו.

Rambam’s formulation is taken from Aristotle:

Virtue, then, is a state of character concerned with choice, lying in a mean, i.e. the mean relative to us, this being determined by a rational principle, and by that principle by which the man of practical wisdom [phronesis] would determine it. Now it is a mean between two vices, that which depends on excess and that which depends on defect; and again it is a mean because the vices respectively fall short of or exceed what is right in both passions and actions, while virtue both finds and chooses that which is intermediate.

But Rambam is just using the language of Aristotle to present the ideas of חכמים הראשונים. The idea of the “Golden Mean”, the שביל הזהב or דרך האמצע, is inherent in ספר משלי.

[ומשרים:] כמ׳׳ש הרמב״ם בהלכות דעות; אמר אצלם (ישעיהו יא:ד) וְשָׁפַט בְּצֶדֶק […הוֹכִיחַ בְּמִישׁוֹר]. הן הב׳ מדות צדק ומשפט כי הן צריכין לזה לכל א׳ הפכו.

Then Shlomo tells us his intended audience. He addresses four people:

ד לתת לפתאים ערמה; לנער דעת ומזמה׃ ה ישמע חכם ויוסף לקח; ונבון תחבלות יקנה׃

We will have to look at the kinds of people that Shlomo does not address later, but these here, even those who are not חכמים ונבונים, have value and can be taught.

לתת לפתאים ערמה

What is a פתי?

פתי יאמין לכל דבר; וערום יבין לאשרו׃

The פתי is naive, easily swayed (from the root לפתות, to entice or seduce). ערום means clever, and in תנ״ך it is generally a bad thing.

והנחש היה ערום מכל חית השדה אשר עשה ה׳ אלקים; ויאמר אל האשה אף כי אמר אלקים לא תאכלו מכל עץ הגן׃

מפר מחשבות ערומים; ולא תעשנה ידיהם תשיה׃

But in משלי, it is a positive thing, a contrast with the naivité of the פתי. Being a פתי is not itself a bad thing; there is a place for what we call אמונה פשוטה. Shlomo is not going to turn the פתי into an ערום; he is just going to give them a little ערמה.

שמר פתאים ה׳; דלותי ולי יהושיע׃

And the greatest נביא of all is described as a פתי:

(שמות ג:ו) וַיֹּאמֶר אָנֹכִי אֱלֹקֵי אָבִיךָ. הדא הוא דכתיב: פֶּתִי יַאֲמִין לְכָל דָבָר…אמר רבי יהושע הכהן בר נחמיה: בשעה שנגלה הקדוש ברוך הוא על משה טירון היה משה לנבואה, אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא אם נגלה אני עליו בקול גדול אני מבעתו; בקול נמוך בוסר הוא על הנבואה. מה עשה? נגלה עליו בקולו של אביו; אמר משה הנני, מה אבא מבקש? אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא: איני אביך אלא אלקי אביך, בפתוי באתי אליך כדי שלא תתירא.

It can be a good thing; the Artscroll Mishlei says פתי is synonymous with תם, which can be translated both as “simple” and as “perfect”:

ויגדלו הנערים ויהי עשו איש ידע ציד איש שדה; ויעקב איש תם ישב אהלים׃

ידע ציד: לצוד ולרמות…

תם: אינו בקי בכל אלה, כלבו כן פיו, מי שאינו חריף לרמות קרוי תם.

תמים תהיה עם ה׳ אלקיך׃

And that is relevant to פסח that is coming up. We read about the four sons:

חכם, מה הוא אומר? מָה הָעֵדוֹת וְהַחֻקִּים וְהַמִּשְׁפָּטִים אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה ה׳ אֱלֹקֵינוּ אֶתְכֶם? ואף אתה אמור לו כהלכות הפסח: אין מפטירין אחר הפסח אפיקומן…

תם, מה הוא אומר? מַה זּאֹת? ואמרת אליו בְּחוֹזֶק יָד הוֹצִיאָנוּ ה׳ מִמִּצְרַיִם מִבֵּית עֲבָדִים…

Why does the haggadah say, about the חכם: אף אתה אמור לו—you should even tell him? It is because the answer given in the haggadah is not the answer the Torah gives:

כ כי ישאלך בנך מחר לאמר; מה העדת והחקים והמשפטים אשר צוה ה׳ אלקינו אתכם׃ כא ואמרת לבנך עבדים היינו לפרעה במצרים; ויציאנו ה׳ ממצרים ביד חזקה׃ כב ויתן ה׳ אותת ומפתים גדלים ורעים במצרים בפרעה ובכל ביתו לעינינו׃ כג ואותנו הוציא משם למען הביא אתנו לתת לנו את הארץ אשר נשבע לאבתינו׃

The answer in the haggadah is the last tosefta in מסחת פסחים. It is תורה שבעל פה.

אין מפטירין אחר הפסח [אפיקומן] כגון [אגוזים] תמרים [וקליות]. חייב אדם [לעסוק בהלכות הפסח] כל הלילה…מעשה ברבן גמליאל וזקנים שהיו מסובין בבית ביתוס בן זונין בלוד והיו [עסוקין בהלכות הפסח] כל הלילה עד קרות הגבר.

Notice the story, the מעשה with Rabbis at the seder all night. It is a different story from the one brought in the haggadah:

מעשה ברבי אליעזר ורבי יהושע ורבי אלעזר בן עזריה ורבי עקיבא ורבי טרפון, שהיו מסבין בבני־ברק, והיו מספרים ביציאת מצרים כל אותו הלילה, עד שבאו תלמידיהם ואמרו להם רבותינו הגיע זמן קריאת שמע של שחרית.

Notice the key difference: in the תוספתא, the rabbis are עסוקין בהלכות הפסח. In the Haggadah, they are מספרים ביציאת מצרים. So when the בעל הגדה says ואף אתה אמור לו כהלכות הפסח, the בעל הגדה is giving us a התר, that we may spend our night עוסקין בהלכות הפסח. Once you’ve fulfilled the mitzvah of והגדת לבנך…בעבור זה עשה ה׳ לי בצאתי ממצרים and (as the Torah explicitly says) ואמרת לבנך עבדים היינו לפרעה במצרים; ויציאנו ה׳ ממצרים ביד חזקה, then you can indulge his intellectual fervor for the halacha. But the בעל הגדה does not hold like the Tosefta. It’s not ideal. The ideal is the “perfect” son, the תם. He asks about the story of יצאת מצרים, and you tell him the story of יצאת מצרים.

I like to ask the people around the seder table which of the four sons they would like to be. Predictably, almost everyone would like to be the ben chacham. Personally, however, I have a soft spot for the ben tam. If I could be anyone, I would like to be him.

There are times and places where you should not be so much of a חכם and ערום. But being a תם, a פתי, can be dangerous. One is too easily swayed in the wrong direction. So Shlomo wants לתת לפתאים ערמה, not to change the תם, but to give them a little cleverness that allows them to fight back. It is part of the מוסר השכל of משרים, the מדה בינונית.

[ויגד יעקב לרחל] כי אחי אביה הוא:…ומדרשו, אם לרמאות הוא בא, גם אני אחיו ברמאות, ואם אדם כשר הוא, גם אני בן רבקה אחותו הכשרה.

לנער דעת ומזמה

This clause is similar. A נער can be used to mean “fool”; that is what it means in Yiddish.

נער: שוטה ואין ראוי לגדלה.

But here is seems to be more literal; a youth is one without experience and therefore acts rashly.

לנער: למי שהוא רך בשנים אשר יעשה מעשיו בבלי דעת ובלי מחשבה קדומה.

[A] young man of practical wisdom [phronesis] cannot be found. The cause is that such wisdom is concerned not only with universals but with particulars, which become familiar from experience, but a young man has no experience, for it is length of time that gives experience.

Like ערמה, in תנ״ך the word זמם, מזמה, is a bad thing. The word literally means “planning, foresight” but usually it is used for plotting evil.

ועשיתם לו כאשר זמם לעשות לאחיו; ובערת הרע מקרבך׃

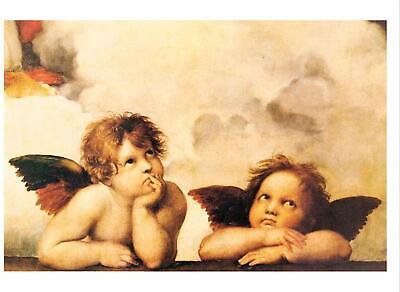

But here, it is a contrast, a balance to נאַרישקײַט which isn’t really foolishness but youthfulness, the ability to grow and change. Just like being a פתי is important, being a נער is important. The כרובים on the ארון were images of children.

The cherubim do not represent G-d or angels, but us. We look at them looking at the scene and identify with them, or should identify with them. They summon us to have a child-like wonder, to be naifs, beginners. Why is this important? Why is it important to have at the center of the Temple, at the boundary between the human and the transcendent?

…Hannah Arendt describes natality, newness, as the primary phenomenon that can liberate us from the oppression of systematic thinking. I see the cherubim as figures of natality.

Shlomo wants to give לנער דעת ומזמה. He tells the נער: don’t stop being a נער; don’t stop looking at the world with child-like eyes. But read ספר משלי and learn from the experience of others. Then you will be able to think about the consequences of your actions.

איזהו חכם? הרואה את הנולד.