Last time, we discussed the idea that שירה, the song of the Levites in the Temple, was commanded in the Torah from the verse,

וְכִי יָבֹא הַלֵּוִי מֵאַחַד שְׁעָרֶיךָ מִכָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר הוּא גָּר שָׁם; וּבָא בְּכָל אַוַּת נַפְשׁוֹ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר יִבְחַר יְדוָד׃

ז וְשֵׁרֵת בְּשֵׁם יְדוָד אֱ־לֹהָיו כְּכָל אֶחָיו הַלְוִיִּם הָעֹמְדִים שָׁם לִפְנֵי יְדוָד׃

and the Gemara says (ערכין יא,א) איזהו שירות שבשם? הוי אומר זה שירה. Phyllis Shapiro noted that שֵׁרוּת, service, and שִׁירָה, song,look like they ought to have some liguistic connection. But I can’t find anything. The gemara there is willing to say אל תיקרי יָסֹר אלא יָשִׁיר to learn the laws of שירה, but nothing about שֵׁרוּת.

Even Hirsch, who has a whole system of etymological derivations, has nothing. In the Etymological Biblical Dictionary of Hebrew, based on Rav Hirsch’s writings, associates שרת, serve, with שרד, separate, and שרט, cut. שיר, sing, is associated with many roots like סיר, contain, ציר, connect, ישר, strengthen, and שרר, concentrate. But they are not connected to each other.

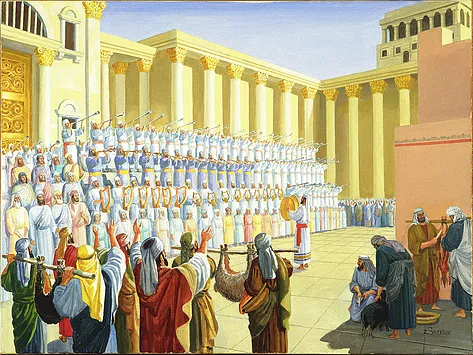

So if שירה is a מצוה דאוריתא, then what was David’s innovation? We know he set up a system and a schedule for the שירה, and wrote the words (and possibly the music) for much of what was later used in the בית המקדש, but the biggest innovation seems to be the instrumental accompaniment. There’s an argument in the Mishna about who played the instruments:

ועבדי הכוהנים היו, דברי רבי מאיר…רבי חנניה בן אנטיגנוס אומר, לויים היו.

And the Gemara tries to connect this to the question of whether the מצוה of שירה was the vocal song, or the instrumentation:

לימא בהא קמיפלגי דמ״ד עבדים היו קסבר עיקר שירה בפה וכלי לבסומי קלא הוא דעבידא ומ״ד לוים היו קסבר עיקר שירה בכלי…לעולם קסבר: עיקר שירה בפה.

The conclusion is that it is the vocals that are the essence of the מצוה, and we would conclude from our reading of תנ״ך that in fact David introduced the instruments.

This has implications להלכה:

תנו רבנן: החליל דוחה את השבת, דברי רבי יוסי בר יהודה, וחכמים אומרים: אף יום טוב אינו דוחה. אמר רב יוסף: מחלוקת בשיר של קרבן, דרבי יוסי סבר: עיקר שירה בכלי, ועבודה היא, ודוחה את השבת. ורבנן סברי: עיקר שירה בפה, ולאו עבודה היא, ואינה דוחה את השבת. אבל שיר של שואבה—דברי הכל שמחה היא ואינה דוחה את השבת.

However, playing instruments should not be a problem even if there is no מצוה, since the whole concept of שבות, the rabbinic prohibitions that “surround” the laws of Shabbat, don’t apply in the מקדש:

אין שבות במקדש הוא כלל בהלכות שבת הקובע שדברים שחכמים אסרום משום שבות, אינם אסורים במקדש.

הטעם שאין שבות במקדש, לפי שהכהנים זריזים הם, ויודעים להיזהר שלא יבואו לידי איסור תורה. ולפיכך לא גזרו חכמים על שבות במקדש.

[ראה עירובין קב,ב ]

Tosaphot explains that the argument is about tuning or repairing the instruments:

ורבנן סברי עיקר שירה בפה: תימה…לא פליגי אלא בתיקון כלי אי דחי שבת משום מכשירי קרבן אבל שיר עצמו לכ״ע דחי.

The Ritva says that תיקון כלי is so automatic for a musician that the גזירה against playing applied even in the מקדש:

תנו רבנן חליל דוחה את השבת כו׳…וק״ל דהא איסור נגון בחליל וכלי זמר אינו אלא שבות דרבנן שמא יתקן כלי שיר וקיימא לן דאין שבות במקדש ואם כן אף על גב דעיקר שירה בפה ואין כלי מעכב למה לא יהא חליל דוחה את השבת?…וי״ל דכל כי האי שבות שהוא דבר מצוי דאתי לידי תיקון כלי שיר דאיסורא שהתיקון מצוי בהם אפילו במקדש גזרו בו כשאינו מעכב דאגב טרדייהו אתו ומתקני ליה…ולפיכך אסור למאן דאמר עיקר שירה בפה…

And the question of repair remains an argument in the gemara:

דתניא: בן לוי שנפסקה לו נימא בכנור, קושרה. רבי שמעון אומר: עונבה. רבי שמעון בן אלעזר אומר: אף היא אינה משמעת את הקול, אלא משלשל מלמטה וכורך מלמעלה, או משלשל מלמעלה וכורך מלמטה.

The bottom line remains that the real commandment is the vocal song. The instruments are only incidental, כלי לבסומי קלא הוא דעבידא.

In fact, the instruments are always attributed to David:

ה ויזבח המלך שלמה את זבח הבקר עשרים ושנים אלף וצאן מאה ועשרים אלף; ויחנכו את בית האלקים המלך וכל העם׃

ו והכהנים על משמרותם עמדים והלוים בכלי שיר ה׳ אשר עשה דויד המלך להדות לה׳ כי לעולם חסדו בהלל דויד בידם; והכהנים מחצצרים (מחצרים) נגדם וכל ישראל עמדים׃

Similarly in the time of Chizkiyah:

כה ויעמד את הלוים בית ה׳ במצלתים בנבלים ובכנרות במצות דויד וגד חזה המלך ונתן הנביא; כי ביד ה׳ המצוה ביד נביאיו׃

כו ויעמדו הלוים בכלי דויד והכהנים בחצצרות׃

What does adding the instrumental accompaniment do for the שירה?

It turns the שירה from an incidental part of the עבודה to the focus of the service. This changes the nature of the עבודה. When it’s just the sacrifice of a lamb, then it just involves a few כהנים. Now it is possible to have an audience, and even to have the people participate (we’ve talked about the nature of the refrain הודו לה׳ כי טוב כי לעולם חסדו). Over the next few weeks, I want to look in detail at the lyrics of the songs he writes for that עבודה.

The Vilna Gaon talked about the importance of music in our own time:

בהקדמה לספר ”פאת השולחן“, מספר ר׳ ישראל משקלוב, שכאשר הגאון מוילנא סיים את פרושו על שיר השירים, הוא שמח שמחה גדולה מאד, וכך הוא מתאר את הארוע:

וצוה לסגור חדרו, והחלונות סוגרו ביום, והדליקו נרות הרבה. וכאשר סיים פרושו, נשא עיניו למרום בדביקות עצומה, בברכה והודאה לשמו הגדול יתברך שמו, שזיכהו להשגת אור כל התורה בפנימיותה וחוצותיה.

כה אמר:

”כל החוכמות נצרכים לתורתינו הקדושה וכלולים בה, וידעם כולם לתכליתם. והזכירם: חכמת האלגברה, המשולשים וההנדסה, וחוכמת מוסיקה, ושיבחה הרבה. הוא היה אומר אז, כי רוב טעמי תורה וסודות שירי הלויים, וסודות תיקוני הזהר, אי אפשר לידע בלעדה [בלי חכמת המוזיקה אי אפשר ללמוד סודות התורה] ועל ידה יכולים בנ״א למות, בכלות נפשם בנעימותיה, ויכולים להחיות מתים בסודותיה הגנוזים בתורה. הוא אמר כמה ניגונים וכמה מידות הביא משרע״ה מהר סיני [המקור של הניגונים הוא גם כן מהר סיני] והשאר מורכבים.“

וביאר איכות כל החוכמות ואמר שהשיגם לתכליתם—כי הוא חשב שהכל הכרחי להבנת התורה. רק לגבי חכמת הרפואה הוא אמר: ידע חכמת הניתוח, והשייך אליה, אך מעשה הסמים ומלאכתם למעשה, רצה ללמדם מרופאי הזמן, וגזר עליו אביו הצדיק שלא ילמדנה, כדי שלא יבטל מתורתו, שיצטרך ללכת להציל נפשות כשידע לגומרה.

This week is תשעה באב, and I will conclude with a note about the last שירה in the בית המקדש:

ת״ש: רבי יוסי אומר: מגלגלין זכות ליום זכאי וחובה ליום חייב. אמרו: כשחרב הבית בראשונה, אותו היום תשעה באב היה, ומוצאי שבת היה, ומוצאי שביעית היתה, ומשמרתו של יהויריב היתה, והיו כהנים ולוים עומדים על דוכנן ואומרים שירה, ומה שירה אמרו? ”וישב עליהם את אונם וברעתם יצמיתם“, ולא הספיקו לומר יצמיתם ה׳ אלקינו עד שבאו אויבים וכבשום…אמר רבא, ואיתימא רב אשי: ותסברא? שירה דיומיה לה׳ הארץ ומלואה, וישב עליהם את אונם בשיר דארבעה בשבת הוא! אלא אילייא בעלמא הוא דנפל להו בפומייהו. והא עומדין על דוכנן קתני! כדר״ל, דאמר: אומר שלא על הקרבן.

א א־ל נקמות ה׳; א־ל נקמות הופיע׃

ב הנשא שפט הארץ; השב גמול על גאים׃

…כג וישב עליהם את אונם וברעתם יצמיתם;

יצמיתם ה׳ אלקינו׃

The image of the Levites playing on as the Temple burns around them reminds us of a more recent disaster:

After the Titanic hit an iceberg and began to sink, Hartley and his fellow band members started playing music to help keep the passengers calm as the crew loaded the lifeboats. Many of the survivors said that Hartley and the band continued to play until the very end. One second class passenger said:

Many brave things were done that night, but none were more brave than those done by men playing minute after minute as the ship settled quietly lower and lower in the sea. The music they played served alike as their own immortal requiem and their right to be recalled on the scrolls of undying fame.