We’ve spent a lot of time looking at Hallel, as part of the concept of הלל והודאה. I want to look at two perakim of תהילים that are specifically about the physical expression of הודאה, the קרבן תודה. The first is תהילים ק, which is titled מזמור לתודה, and was the שיר sung when a קרבן תודה was brought:

מזמור לתודה: להודיה לאומרו על זבחי תודה.

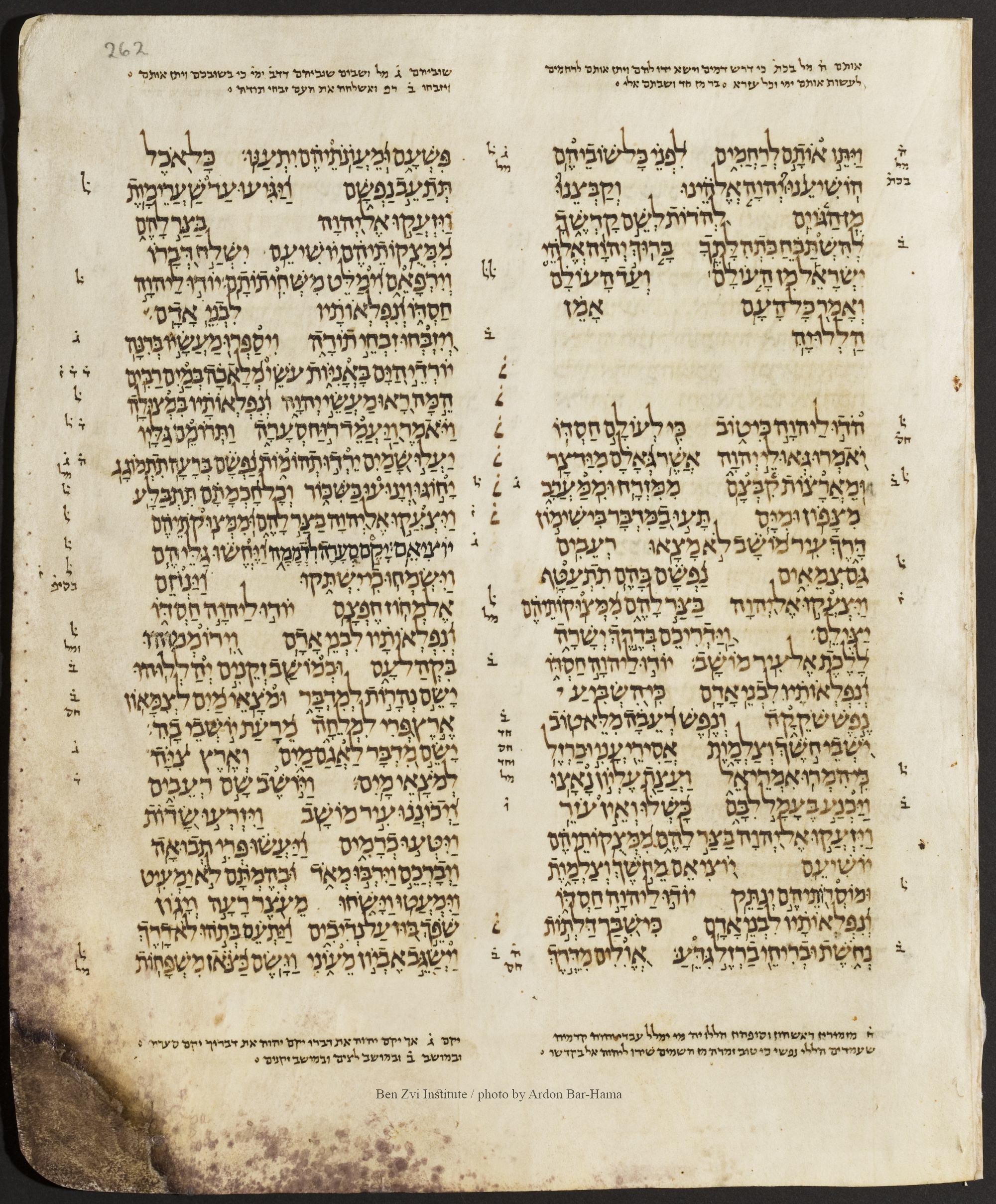

The second is תהילים קז, which starts like a “Hallel”: הדו לה׳ כי טוב; כי לעולם חסדו׃ but is actually a long list of situations when a קרבן תודה is brought. The refrain is ויזעקו אל ה׳ בצר להם; ממצקותיהם יושיעם׃ and then יודו לה׳ חסדו; ונפלאותיו לבני אדם׃ ויזבחו זבחי תודה; ויספרו מעשיו ברנה׃. It’s where we get the laws of ברכת גומל today.

So what is a קרבן תודה? It is a kind of שלמים, brought to the בית המקדש but eaten by the owners:

יא וזאת תורת זבח השלמים אשר יקריב לה׳׃ יב אם על תודה יקריבנו והקריב על זבח התודה חלות מצות בלולת בשמן ורקיקי מצות משחים בשמן; וסלת מרבכת חלת בלולת בשמן׃ יג על חלת לחם חמץ יקריב קרבנו על זבח תודת שלמיו׃ יד והקריב ממנו אחד מכל קרבן תרומה לה׳; לכהן הזרק את דם השלמים לו יהיה׃ טו ובשר זבח תודת שלמיו ביום קרבנו יאכל; לא יניח ממנו עד בקר׃ טז ואם נדר או נדבה זבח קרבנו ביום הקריבו את זבחו יאכל; וממחרת והנותר ממנו יאכל׃ יז והנותר מבשר הזבח ביום השלישי באש ישרף׃ יח ואם האכל יאכל מבשר זבח שלמיו ביום השלישי לא ירצה המקריב אתו לא יחשב לו פגול יהיה; והנפש האכלת ממנו עונה תשא׃

כט וכי תזבחו זבח תודה לה׳ לרצנכם תזבחו׃ ל ביום ההוא יאכל לא תותירו ממנו עד בקר; אני ה׳׃ לא ושמרתם מצותי ועשיתם אתם; אני ה׳׃ לב ולא תחללו את שם קדשי ונקדשתי בתוך בני ישראל; אני ה׳ מקדשכם׃

We’ve talked many times about the קרבן שלמים: it is not a sacrifice but a barbecue. Only the inedible חלב is offered on the מזבח; the meat is eaten by the בעל, the כהן, and by the entire community. It is a חילול ה׳ to save the meat and not offer it to others (there’s no way one person, or even one family, can eat an entire cow in a single day). That is why זבחי תודה are connected to ויספרו מעשיו ברנה. I need to tell the story, over and over again, of how ה׳ saved me, what I am bringing this זבח for.

And that leads to a fascinating midrash:

רַבִּי פִּנְחָס וְרַבִּי לֵוִי וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן בְּשֵׁם רַבִּי מְנַחֵם דְּגַלְיָא: לֶעָתִיד לָבוֹא כָּל הַקָּרְבָּנוֹת בְּטֵלִין וְקָרְבַּן תּוֹדָה אֵינוֹ בָּטֵל; כָּל הַתְּפִלּוֹת בְּטֵלוֹת, הַהוֹדָאָה אֵינָהּ בְּטֵלָה. הֲדָא הוּא דִכְתִיב (ירמיה לג:יא): ”קוֹל שָׂשׂוֹן וְקוֹל שִׂמְחָה קוֹל חָתָן וְקוֹל כַּלָּה קוֹל אֹמְרִים הוֹדוּ אֶת ה׳ צְבָאוֹת וגו׳“, זוֹ הוֹדָאָה. (ירמיה לג:יא): ”מְבִאִים תּוֹדָה בֵּית ה׳“, זֶה קָרְבַּן תּוֹדָה. וְכֵן דָּוִד אוֹמֵר (תהלים נו:יג): ”עָלַי אֱלֹקִים נְדָרֶיךָ אֲשַׁלֵּם תּוֹדֹת לָךְ;, ”תּוֹדָה“ אֵין כְּתִיב כָּאן אֶלָּא ”תּוֹדֹת“, הַהוֹדָאָה וְקָרְבַּן תּוֹדָה.

Rav Nahum Rabinovitch explains this based on the gemara:

ההוא דנחית קמיה דרבי חנינא, אמר: הא־ל הגדול הגבור והנורא והאדיר והעזוז והיראוי החזק והאמיץ והודאי והנכבד. המתין לו עד דסיים, כי סיים אמר ליה: סיימתינהו לכולהו שבחי דמרך? למה לי כולי האי? אנן הני תלת דאמרינן—אי לאו דאמרינהו משה רבינו באורייתא, ואתו אנשי כנסת הגדולה ותקנינהו בתפלה—לא הוינן יכולין למימר להו, ואת אמרת כולי האי ואזלת! משל, למלך בשר ודם שהיו לו אלף אלפים דינרי זהב, והיו מקלסין אותו בשל כסף, והלא גנאי הוא לו!

זוהי המשמעות של דברי בעל המדרש: לעתיד לבוא, כאשר תתרבה ידיעת ה׳ עד קצה גבול יכולתו של האדם, כל ההודאות בטלות כי הוא יכיר שאין מה להגיד…כל מה שאומרים, כל תואר, כל שבח שמייחסים לה׳ מצמצם ומקטין כי הוא מנסה להביע את מה שלא ניתן להבעה ונכשל.

In the עתיד לבא, we will have a much better understanding of the nature of הקב״ה, which will only serve to emphasize how much we don’t understand, to the point that we will realize that we can never praise ה׳. But gratitude is different. The more we realize ה׳'s role in our lives, the more we will express that gratitude.

אולם, מאידך, הודאת התודה אינה בטלה. מה הכוונה באמירה הזו? בפועל יש כאן שני תהליכים שהולכים יחדיו, מתאימים ומקבילים. כדי להבין זאת יש לעשות תרגיל מחשבתי—כמה אנו שואלים את עצמנו מה הקב״ה נתן לנו היום? כמעט ולא שואלים את השאלה הזו כלל. יש הזדמנויות של התעלות, אירועים בהם אדם ניצל מאיזו סכנה או רגעים אחרים בהם אדם מרגיש צורך נפשי להודות לקב״ה על חסדו, אבל ככלל אלו אירועים ממוקדים ודי נדירים. כל העולם כולו, כל החיים כולם, כל מה שמתרחש ביומיום—אין אנו רואים בזה מתנה שיש להודות עליה. בעל המדרש אומר לנו שהנטייה הזו נובעת מחוסר ידיעת ה׳. לעתיד לבוא, כאשר אדם יגיע לדרגה מעולה של ידיעת ה׳, הוא יתחיל להכיר בדברי המשנה (סנהדרין ד:ה): ”בשבילי נברא העולם“. כל מה שיש בעולם, הכל, הוא כדי שכל אחד יחיה את הרגע שהוא חי עכשיו. לא ניתן לאדם לחיות אף רגע אחד בלי שיהנה מן העולם, מן המציאות, בעצם היותו. כל רגע בחיים על כל מה שיש בו הוא מתנה מאת ה׳.

The קרבן תודה is similar. When the midrash talks of הַקָּרְבָּנוֹת בְּטֵלִין, it is talking about private קרבנות. When we get to a point of דרגה מעולה של ידיעת ה׳, we will not need to bring קרבנות.

מביאים תודה בית ה׳: ולא אמר חטאת ואשם לפי שבזמן ההוא לא יהיו בהם רשעים וחוטאים כי כלם ידעו את ה׳ וכן אמרו רז״ל כל הקרבנות בטלים לעתיד לבוא חוץ מקרבן תודה.

לא ירעו ולא ישחיתו בכל הר קדשי; כי מלאה הארץ דעה את ה׳ כמים לים מכסים׃

ובמדרש: כל הקרבנות בטלין וקרבן תודה אינו בטל; כל התפילות בטלות וההודאה אינה בטילה…והיינו קרבנות יחיד, שהתורה לא תשתנה לעולם ויביאו קרבנות צבור, אך קרבנות הבאים על חטא כמו שאמרו במדרש (תנחומא פרשת צו ז) שכל הקרבנות באין על חטא, חטאת ואשם, ואף עולה באה על הרהור הלב, ולעתיד לבוא שיבוער השאור שבעיסה ולא יהיה שום חטא יתבטל כל קרבנות יחיד לבד קרבן שלמים שהראשון שבהם תודה, והיה בא לתת הודאה על אשר ניצול משאור שבעיסה, ולעתיד שיהיה ה׳ אחד ושמו אחד ויהיה כולו הטוב והמיטיב.

כולו הטוב והמיטיב is a reference to the gemara that says that לעתיד לבא, we will understand ה׳'s role in the world and His goodness in all that He does, and we will appreciate even the apparently negative things in life:

(זכריה יד:ט) .וְהָיָה ה׳ לְמֶלֶךְ עַל כׇּל הָאָרֶץ בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא יִהְיֶה ה׳ אֶחָד וּשְׁמוֹ אֶחָד: אטו האידנא לאו אחד הוא? אמר רבי אחא בר חנינא: לא כעולם הזה העולם הבא. העולם הזה, על בשורות טובות אומר: ”ברוך הטוב והמטיב“, ועל בשורות רעות אומר: ”ברוך דיין האמת“. לעולם הבא, כולו ”הטוב והמטיב“.

So our goal for the world is to be left with only one form of prayer and one form of קרבן, the תודה. And that is why we stand for מזמור לתודה in פסוקי דזימרא:

מזמור לתודה יש לאומרה בנגינה, שכל השירות עתידות ליבטל חוץ ממזמור לתודה.

With that, let’s look at תהילים ק, the psalm of the thanksgiving offering.

א מזמור לתודה;

הריעו לה׳ כל הארץ׃

ב עבדו את ה׳ בשמחה; באו לפניו ברננה׃

ג דעו כי ה׳ הוא אלקים;

הוא עשנו ולא (ולו) אנחנו

עמו וצאן מרעיתו׃

ד באו שעריו בתודה חצרתיו בתהלה; הודו לו ברכו שמו׃

ה כי טוב ה׳ לעולם חסדו; ועד דר ודר אמונתו׃

The good news is that it is short, so it should be easy to analyze. The bad news is that it is short, so despite its importance (we stand when we say it), we mumble it quickly and never pay attention to the words. The other bad news is that it isn’t actually easy to analyze; being short just means it is being poetic and ambiguous. Rav Elchanan Samet has a 15 page essay on these 5 psukim.

We won’t spend that much time on it. But it’s importance is highlighted by its authorship: it dates back to Moshe himself:

אמר רבי לוי בשם רבי חנינא: אחד עשר מזמורים שאמר משה בטכסיס של נבואה אמרן. ולמה לא נכתבו בתורה? אלו דברי תורה ואלו דברי נבואה.

(I think that דברי נבואה shouldn’t be taken literally; ספר תהילים is in כתובים. Moshe sometimes writes ברוח הקרש, not at the level באספקלריא המאירה.)

These are the eleven:

- תפלה למשה איש האלקים

- ישב בסתר עליון

- מזמור שיר ליום השבת

- ה׳ מלך גאות לבש

- א־ל נקמות ה׳

- לכו נרננה לה׳

- שירו לה׳ שיר חדש

- ה׳ מלך תגל הארץ

- מזמור שירו לה׳ שיר חדש

- ה׳ מלך ירגזו עמים

- מזמור לתודה

So our מזמור לתודה (at least in some prototypical form) goes back to the time of the משכן.

The perek itself is a chiasm: it starts with a call to all people, הריעו לה׳ כל הארץ and ends with the common refrain, כי טוב ה׳ לעולם חסדו; ועד דר ודר אמונתו. That’s not the קרבן; that’s the verbal praise. The next line is עבדו את ה׳ בשמחה; באו לפניו ברננה which again, is non-specific. The corresponding second-to-last line is specific: באו שעריו בתודה חצרתיו בתהלה; הודו לו ברכו שמו. Here we have the קרבן along with the verbal praise.

The reason for the change is in the middle section. We go from דעו כי ה׳ הוא אלקים, a universal, intellectual relationship with הקב״ה, to עמו וצאן מרעיתו: we, the Jewish people, are G-d’s people.

The volta is the ambiguous center line: הוא עשנו ולא אנחנו, the כתיב, is a statement about creation. ה׳ created the world and therefore we need to serve Him. הוא עשנו ולו אנחנו, the קריא, is about relationship. ה׳ not only created us but made us His people. That is why the שלמים is a form of עבודה. It’s not about the sacrifice; it’s about sharing a meal, as it were, with הקב״ה. The idea of שלמים was an innovation:

אמר מר: והכל [לפני קיום המשכן] קרבו עולות. עולות אין; שלמים לא…ר״א ור׳ יוסי בר חנינא: חד אמר קרבו [שלמים בני נח], וחד אמר לא קרבו.

זו מסייעת לר׳ יוסי בר׳ חנינא (שיר השירים ד:טז): עוּרִי צָפוֹן וּבוֹאִי תֵימָן [הָפִיחִי גַנִּי יִזְּלוּ בְשָׂמָיו יָבֹא דוֹדִי לְגַנּוֹ וְיֹאכַל פְּרִי מְגָדָיו]. עוּרִי צָפוֹן—זו עולה שנשחטה בצפון. ולמה קורא אותה “עורי”? דבר שהיה ישן ונתעורר. וּבוֹאִי תֵימָן—אלו שלמים שנשחטו בדרום, ולמה קורא אותה ”ובואי תימן“? דבר שהוא לחידוש. אף המקרא מסייע לר׳ יוסי בר חנינה (ויקרא ו:ב):זֹאת תּוֹרַת הָעֹלָה, הִוא הָעֹלָה—שהקריבו בני נח. ועכשיו שבאו שלמים (ויקרא ז:יא): זֹאת תּוֹרַת זֶבַח הַשְּׁלָמִים אֲשֶׁר יַקְרִיב לַה׳—״אשר הקריבו לה׳" לא כתוב כאן, אלא: ”אשר יקריב לה׳“, מכאן ולהבא.

And that is reflected in our perek. The first half is addressed to the world, “serve G-d”. The second half is addressed to עם ישראל and adds “join Him in this holy meal”.

ההבחנה הראשונה בין שתי המחציות, שכבר עמדנו עליה, היא כמובן בנמענים שאליהם מופנות הקריאות להלל: במחצית הראשונה—הנמען הוא כללי-אוניברסלי: ”כָל הָאָרֶץ“; במחצית השנייה—הנמען הוא עם ישראל: ”עמֹו וְׁצאן מרְׁעִּיתֹו“.

It is only when we have a personal relationship with הקב״ה that the קרבן שלמים makes any sense.

אנו שואלים: מה כל כך חשוב בשאלה אם בני נח הקריבו עולות ושלמים? מאי נפקא מיניה? בשל מה הדיון הארוך הזה וחזרתה של הדרשה במספר כה רב של מקורות? ובפרט לשיטת ר׳ יוסי בר׳ חנינא, למה חשוב לו להוכיח ששלמים הוא חידוש של התורה, של ספר ויקרא?

…אם קרבן שלמים הוא “גולת הכותרת” והפרפרת, הוא הקרבן הרצוי משום שיש בו שלום, שלמות ושמחה, שבא בד״כ בנדבה ולפיכך “לעתיד לבוא כל הקורבנות בטילין וקרבן תודה אינו בטל לעולם. כל ההודיות בטלות והודיית תודה אינה בטלה לעולם”…אם כך, לא מוכן ר׳ יוסי בר׳ חנינא “לתת” אותו לבני נח. הוא מעדיף מצב שבו אומות העולם, וגם אבות האומה, ובני ישראל עד רגע לפני מתן תורה וציווי הקרבנות, הקריבו עולות—כליל למזבח. באה תורת הקרבנות ומגדירה פרטי דינים אלה, ומוסיפה קרבן שלא היה מוכר בעולם, קרבן של שותפות ושלום, של ”חציו לה׳ וחציו לכם“, חלק לגבוה וחלק להדיוט, קרבן שיש לשתף בו אנשים רבים כי זמן אכילתו ומקומו מוגבלים. קרבן של שלמות ושמחה ובעל תוקף גם כאשר כל הקרבנות יתבטלו. כיצד (גם אחרי שבטל המקדש)? בתפילת הודיה שלעולם לא תתבטל. זה המסר החשוב כל כך לר׳ יוסי בר׳ חנינא שלמענו הוא טורח לפרק את כל הוכחותיו וטענותיו של ר׳ אלעזר ולהציע הוכחות משלו.

So why have the first, universal, half, if the perek is meant to be a מזמור לתודה? Because our goal is that, through the invitation to join the תודה and the הודו לו ברכו שמו that accompanies it, the entire world will come to acknowlege ה׳.

הבה נשוב למחצית הראשונה של מזמורנו ונאמר את מה שנראה מובן מאליו: הקריאה ל”כל הארץ“ להריע לה׳ ולעבדו בשמחה, מתוך הכרה כי הוא לבדו הא-לוהים שבראנו, מתייחסת כמובן לעידן עתידי שבאחרית הימים. קריאה זו אינה מתאימה כלל למציאות הדתית-פוליטית בזמן שבו נתחבר מזמורנו!

…ובכן, הקריאה במזמורנו אל ”כל הארץ“ להריע לה׳ ולעבדו בשמחה צומחת מתוך מצב שבו עם ישראל כבר נגאל בידי ה׳, שהרי בטרם נגאל—אין דבריו ודברי משורריו נשמעים כלל. דבר זה אינו נאמר רק מסברה: גאולתו של עם ישראל היא המצע של המחצית השנייה של מזמורנו, ובמחצית זו מתברר למפרע גם הזמן שאליו מתייחסת מחציתו הראשונה.

Maybe I should say תהילים ק with more כוונה.

The other psalm of the קרבן תודה is תהילים קז. That perek is the beginning of book five of תהילים; the previous perek ends with a coda:

ברוך ה׳ אלקי ישראל מן העולם ועד העולם

ואמר כל העם אמן;

הללויה׃

And book five is the real “siddur” of the בית המקדש; it includes all three of the “Hallel”s along with all the שיר המעלות‘s. Our perek is the introduction to that siddur; it describes those who have to offer thanks and praise to הקב״ה. It’s a long perek, that has four parts: a short introduction; the bulk of the perek that describes four individuals who are saved and have to offer הודאה; a description ה׳’s power over entire nations, when the community has to offer הודאה; then a short conclusion.

The introduction is about praising ה׳ for redeeming Israel and gathering them from exile:

א הדו לה׳ כי טוב; כי לעולם חסדו׃

ב יאמרו גאולי ה׳ אשר גאלם מיד צר׃

ג ומארצות קבצם; ממזרח וממערב; מצפון וּמִיָּם׃

It looks like the pasuk is trying to say that ה׳ gathers them from all four corners of the earth: east, west, north and west. What does that mean? The Koren translation cheats:

and gathered them out of the lands, from the east, and from the west, from the north, and from the south.

But יָם doesn’t mean south; it means west. The Targum takes a similar tack:

וּמֵאַרְעֲתָא כַּנְשִׁינוּן מִמַדִנְחָא וּמִמַעֲרָבָא מִצִפּוּנָא וּמִן יַמָא דָרוֹמָא׃

But the major sea, from the point of view of ארץ ישראל, is in the west. Why mention the Red Sea? Most מפרשים argue that ממזרח וממערב מצפון are directions; ממזרח וממערב is a merism for the entire world:

הזכיר מזרח ומערב כי כן היישוב מן הקצה אל הקצה.

We see this often in תנ״ך:

ממזרח שמש עד מבואו מהלל שם ה׳׃

א ועתה כה אמר ה׳ בראך יעקב ויצרך ישראל; אל תירא כי גאלתיך קראתי בשמך לי אתה׃…ה אל תירא כי אתך אני; ממזרח אביא זרעך וממערב אקבצך׃

And according to Ibn Ezra, north is another populated area, but the land south of Israel is not. ים means literally “the sea”, referring to those lost at sea (which is one of the groups that have to offer a תודה:

הזכיר מצפון, כי שם כל היישוב ולא הזכיר דרום בעבור חום השמש אין שם יישוב בראיות גמורות. וטעם ו”מים“, יורדי הים, כי היורד כתוב מהארבעה הנזכרים.

ומים: מאיי הים.

I don’t like that. There are plenty of people living south of Israel, and why single out those lost at sea? There are three other groups that are mentioned in this perek.

So I will propose my own explanation. ממזרח וממערב means “from one end of the earth to the other”, as we’ve said. The expression מצפון ומים is its own phrase, an idiom that occurs elsewhere in תנ״ך:

הנה אלה מרחוק יבאו; והנה אלה מצפון ומים ואלה מארץ סינים׃

And I remembered my Asimov, that “the ends of the earth” can mean different things:

For four hundred years, so many men have been blinded by Seldon’s words, “the other end of the Galaxy.” They brought their own peculiar physical-science thought to the problem, measuring off the other end with protractors…

The solution could have been reached immediately, if the questioners had but remembered that Hari Seldon was a social scientist…What could ”opposite ends“ mean to a social scientist? Opposite ends on the map? Of course not…

The First Foundation was at the periphery, where the original Empire was weakest…where its wealth and culture were most nearly absent. And where is the social opposite end of the Galaxy? Why, at the place where the original Empire was strongest, where its civilizing influence was most…strongly present.

ביום ההוא כרת ה׳ את אברם ברית לאמר; לזרעך נתתי את הארץ הזאת מנהר מצרים עד הנהר הגדל נהר פרת׃

In Brit Bein HaB’tarim, ”ha’Aretz“ is defined as the land between the Nile and Euphrates. These rivers are not borders; never in the history of mankind have these rivers marked the borders of a single country. Rather, these rivers mark the two centers of ancient civilization —Mesopotamia (“N’har Prat”) and Egypt (“N’har Mitzrayim”).

…We are to become a nation “declaring G-d’s Name” at the crossroads of the two great centers of civilization.

So ומארצות קבצם…מצפון ומים also means "gathered from one [cultural] end of the earth to the other.

והיה ביום ההוא יתקע בשופר גדול ובאו האבדים בארץ אשור והנדחים בארץ מצרים; והשתחוו לה׳ בהר הקדש בירושלם׃

And that vision, of קיבוץ גלויות, is why this perek has been adopted as the “שיר של יום” for יום העצמאות:

מזמור ק״ז בתהילים, הפותח את החלק החמישי של הספר לפי חלוקת המסורה, הוא מזמור גאולה הנאמר ע״י עדות המזרח בפסח, ותוקן ע״י הרבנות הראשית בראשותם של הרב הרצוג והרב עוזיאל להיאמר בפתיחת תפילות ליל יום העצמאות.

The perek then switches from the salvation of the people as a whole, to individuals. The gemara learns many details of the halachot of הודאה from this perek:

אמר רב יהודה אמר רב: ארבעה צריכין להודות: יורדי הים, הולכי מדברות, ומי שהיה חולה ונתרפא, ומי שהיה חבוש בבית האסורים ויצא…מאי מברך? אמר רב יהודה: ”ברוך גומל חסדים טובים“. אביי אמר: וצריך לאודויי קמי עשרה, דכתיב: ”וירוממוהו בקהל עם וגו׳“. מר זוטרא אמר: ותרין מינייהו רבנן, שנאמר: ”ובמושב זקנים יהללוהו“. יחמתקיף לה רב אשי: ואימא כולהו רבנן?!—מי כתיב ”בקהל זקנים“? ”בקהל עם“ כתיב.

When we look at the four cases, they all have a similar structure: 2 to 4 psukim describing their plight, one pasuk describing their prayer, 1 to 2 psukim describing how they were saved, and 2 psukim describing their תודה. But each has different details; for instance, one case has בקהל עם ובמושב זקנים, another has another has ויזבחו זבחי תודה.

כל השיר בנוי על הדמוי ועל השנוי…אנו מגיעים למסקנה אחת: אין מעצור לה׳ להושיע בעל אלה ובכל אלה יש לזעוק לה׳…על כל אלה יש להודות לה׳.

The halachic assumption here is not that the cases are distinct, with different halachot for different kinds of salvation, but that they are all the same. The poetic variation emphasizes that ה׳ can save in many different ways. Sometimes His hand is obvious; sometimes it is hidden. And our inclination to respond to that salvation manifests in different ways. It is the role of the halacha to give a consistent structure to that feeling.

[T]he Torah’s main objective is the translation of the numinous into the kerygmatic…

So let’s look at the four cases. The first is הולכי מדברות:

ד תעו במדבר בישימון דרך; עיר מושב לא מצאו׃

ה רעבים גם צמאים נפשם בהם תתעטף׃

ו ויצעקו אל ה׳ בצר להם; ממצוקותיהם יצילם׃

ז וידריכם בדרך ישרה ללכת אל עיר מושב׃

ח יודו לה׳ חסדו; ונפלאותיו לבני אדם׃

ט כי השביע נפש שקקה; ונפש רעבה מלא טוב׃

The perek starts with those lost in the wilderness, then those imprisioned, then the ill and those lost at sea. The gemara has a different order: יורדי הים, הולכי מדברות, ומי שהיה חולה ונתרפא, ומי שהיה חבוש בבית האסורים ויצא. Some are bothered by that. The בן איש חי says that the gemara is emphasizing the transition from large groups to the individual:

מקשים אמאי לא נקיט להו כסדר דנקיט בכתוב? ונראה לי בס״ד כי יורדי הים לא שייך ביחיד כלל, כי הספינה צריכה למנהיגים על כל פנים, והולכי מדברות שייך לפעמים ביחד, אבל הרוב לא שייך ביחיד אלא רבים הולכים יחד, ולכך נקיט יורדי הים ברישא ואחרי זה הולכי מדברות. אך חולה וחבוש שמצויים ביחיד נקיט להו אחר כך…ובזה יש לתרץ קושיא אחרת למה נקיט יוֹרְדֵי הוֹלְכֵי לשון רבים.

The next case is מי שהיה חבוש בבית האסורים ויצא:

י ישבי חשך וצלמות; אסירי עני וברזל׃

יא כי המרו אמרי א־ל; ועצת עליון נאצו׃

יב ויכנע בעמל לבם; כשלו ואין עזר׃

יג ויזעקו אל ה׳ בצר להם; ממצקותיהם יושיעם׃

יד יוציאם מחשך וצלמות; ומוסרותיהם ינתק׃

טו יודו לה׳ חסדו; ונפלאותיו לבני אדם׃

טז כי שבר דלתות נחשת; ובריחי ברזל גדע׃

The new twist is that now there is a reason for their trouble: they were punished כי המרו אמרי א־ל; ועצת עליון נאצו. Even so, they need to express gratitude for being saved, יודו לה׳ חסדו; ונפלאותיו לבני אדם.

The next case, מי שהיה חולה ונתרפא, also says that they deserved their fate:

יז אולים מדרך פשעם; ומעונתיהם יתענו׃

יח כל אכל תתעב נפשם; ויגיעו עד שערי מות׃

יט ויזעקו אל ה׳ בצר להם; ממצקותיהם יושיעם׃

כ ישלח דברו וירפאם; וימלט משחיתותם׃

כא יודו לה׳ חסדו; ונפלאותיו לבני אדם׃

כב ויזבחו זבחי תודה; ויספרו מעשיו ברנה׃

The next case, יורדי הים, is unique. It’s longer, as the description of their plight starts with the backstory (they are עשי מלאכה במים רבים) and they start admiring ה׳'s handiwork, ראו מעשי ה׳; ונפלאותיו במצולה. But despite this positive description, ה׳ still brings the storm that threatens them: ויאמר ויעמד רוח סערה. Life is like that sometimes; we think we’re doing everything right but everything goes wrong. And we still need to express our gratitude.

׆ כג יורדי הים באניות; עשי מלאכה במים רבים׃

׆ כד המה ראו מעשי ה׳; ונפלאותיו במצולה׃

׆ כה ויאמר ויעמד רוח סערה; ותרומם גליו׃

׆ כו יעלו שמים ירדו תהומות; נפשם ברעה תתמוגג׃

׆ כז יחוגו וינועו כשכור; וכל חכמתם תתבלע׃

׆ כח ויצעקו אל ה׳ בצר להם; וממצוקתיהם יוציאם׃

כט יקם סערה לדממה; ויחשו גליהם׃

ל וישמחו כי ישתקו; וינחם אל מחוז חפצם׃

לא יודו לה׳ חסדו; ונפלאותיו לבני אדם׃

לב וירוממוהו בקהל עם; ובמושב זקנים יהללוהו׃

And there’s another thing that makes this section unique: it’s marked by a series of inverted ׆'s.

No one knows why those marks are there; they are present only in one other place, in פרשת בהעלותך:

׆

לה ויהי בנסע הארן ויאמר משה: קומה ה׳ ויפצו איביך וינסו משנאיך מפניך׃

לו ובנחה יאמר: שובה ה׳ רבבות אלפי ישראל׃

׆

In that case, the gemara discusses the reason:

ויהי בנסוע הארון ויאמר משה: פרשה זו עשה לה הקב״ה סימניות מלמעלה ולמטה לומר

שאין זה מקומה. ר׳ אומר לא מן השם הוא זה אלא מפני שספר חשוב הוא בפני עצמו

We’ve discussed why this section of ספר במדבר is out of place, אין זה מקומה. But how do we explain this section? Why is it “out of place”?

No one, in my opinion, has a good answer. However, Sforno has an interesting suggestion. He points out that the “wandering in the wilderness” sounds familiar:

תעו במדבר: וכזה קרה לישראל בצאתם אל המדבר, שהיו צמאים במרה ורעבים במדבר סין, והוא יתברך השביע נפש שוקקה במרה ”וימתקו המים“, ונפש רעבה מלא טוב במדבר סין, בשליו ולחם שמים.

And the next two can also be connected to יציאת מצרים:

ישבי חשך וצלמות: וזה קרה לישראל בצאתם ממצרים, שהייתה מאסר בית עבדים.

ויגיעו עד שערי מות: וזה קרה לישראל במגפת התלונה, כאמרם (במדבר יז:ו) אַתֶּם הֲמִתֶּם אֶת עַם ה׳, שנרפאו בקטורת, ובדבר הנחשים, שנרפאו בנחש הנחושת.

But יורדי הים באניות doesn’t fit. So Sforno says it is a reference to the future, to the גלות promised in the תוכחה:

סו והיו חייך תלאים לך מנגד; ופחדת לילה ויומם ולא תאמין בחייך׃ סז בבקר תאמר מי יתן ערב ובערב תאמר מי יתן בקר מפחד לבבך אשר תפחד וממראה עיניך אשר תראה׃ סח והשיבך ה׳ מצרים באניות בדרך אשר אמרתי לך לא תסיף עוד לראתה; והתמכרתם שם לאיביך לעבדים ולשפחות ואין קנה׃

וכזה קרה לישראל בגלותם מארצם, כאמרו: וֶהֱשִׁיבְךָ ה׳ מִצְרַיִם בָּאֳנִיּוֹת, ובשובם לעתיד כאמרו (ישעיהו יא:טו) וְהֶחֱרִים ה׳ אֵת לְשׁוֹן יָם מִצְרַיִם.

And it is “out of place” because it hints at a גאולה that hasn’t happened yet: וינחם אל מחוז חפצם. And when that happens, we will be able to say, וירוממוהו בקהל עם.

That serves as a segue to the next section, which talks about ה׳'s providence over countries, causing drought or bringing rain and prosperity:

לג ישם נהרות למדבר; ומצאי מים לצמאון׃

לד ארץ פרי למלחה; מרעת יושבי בה׃

לה ישם מדבר לאגם מים; וארץ ציה למצאי מים׃

לו ויושב שם רעבים; ויכוננו עיר מושב׃

לז ויזרעו שדות ויטעו כרמים; ויעשו פרי תבואה׃

לח ויברכם וירבו מאד; ובהמתם לא ימעיט׃

לט וימעטו וישחו מעצר רעה ויגון׃

׆ מ שפך בוז על נדיבים; ויתעם בתהו לא דרך׃

מא וישגב אביון מעוני; וישם כצאן משפחות׃

And that ties back to the beginning, and the גאולה that starts with קיבוץ גלויות and continues with making the deserts bloom:

א שיר המעלות;

בשוב ה׳ את שיבת ציון היינו כחלמים׃

…ה הזרעים בדמעה ברנה יקצרו׃

ו הלוך ילך ובכה נשא משך הזרע;

בא יבא ברנה נשא אלמתיו׃

And the perek ends with the lesson of the קרבן תודה: we publicly celebrate ה׳'s providence, so that others join us and learn from us:

מב יראו ישרים וישמחו; וכל עולה קפצה פיה׃

מג מי חכם וישמר אלה; ויתבוננו חסדי ה׳׃

מי שהוא חכם ישמור מאלה הדברים האמורים בזה המזמור ישמרם בלבו ויכיר כי ביד האל ית׳ הכל והוא מעלה ומשפיל מעשיר ומוריש ומוחץ ורופא.

And that is true for our national salvation as well.

אז ימלא שחוק פינו ולשוננו רנה; אז יאמרו בגוים הגדיל ה׳ לעשות עם אלה׃