The first of the appendices to ספר שמואל is a tragic story that starts “בימי דוד”:

ויהי רעב בימי דוד שלש שנים שנה אחרי שנה ויבקש דוד את פני ה׳;

ויאמר ה׳ אל שאול ואל בית הדמים על אשר המית את הגבענים׃

Who were the Givonim?

ג וישבי גבעון שמעו את אשר עשה יהושע ליריחו ולעי׃ ד ויעשו גם המה בערמה וילכו ויצטירו; ויקחו שקים בלים לחמוריהם ונאדות יין בלים ומבקעים ומצררים׃ ה ונעלות בלות ומטלאות ברגליהם ושלמות בלות עליהם; וכל לחם צידם יבש היה נקדים׃ ו וילכו אל יהושע אל המחנה הגלגל; ויאמרו אליו ואל איש ישראל מארץ רחוקה באנו ועתה כרתו לנו ברית׃…טו ויעש להם יהושע שלום ויכרת להם ברית לחיותם; וישבעו להם נשיאי העדה׃ טז ויהי מקצה שלשת ימים אחרי אשר כרתו להם ברית; וישמעו כי קרבים הם אליו ובקרבו הם ישבים׃ יז ויסעו בני ישראל ויבאו אל עריהם ביום השלישי; ועריהם גבעון והכפירה ובארות וקרית יערים׃ יח ולא הכום בני ישראל כי נשבעו להם נשיאי העדה בה׳ אלקי ישראל; וילנו כל העדה על הנשיאים׃ יט ויאמרו כל הנשיאים אל כל העדה אנחנו נשבענו להם בה׳ אלקי ישראל; ועתה לא נוכל לנגע בהם׃…כב ויקרא להם יהושע וידבר אליהם לאמר; למה רמיתם אתנו לאמר רחוקים אנחנו מכם מאד ואתם בקרבנו ישבים׃ כג ועתה ארורים אתם; ולא יכרת מכם עבד וחטבי עצים ושאבי מים לבית אֱלֹקָי׃…כו ויעש להם כן; ויצל אותם מיד בני ישראל ולא הרגום׃ כז ויתנם יהושע ביום ההוא חטבי עצים ושאבי מים לעדה; ולמזבח ה׳ עד היום הזה אל המקום אשר יבחר׃

It’s not clear what המית את הגבענים means; there is no recorded death of Givonim in תנ״ך. But (spoiler alert!) the story gets worse from here. Whatever the crime was, the Givonim want revenge, and David hands over almost all of Saul’s surviving descendants. The Givonim kill them all.

It’s a terrible story. You could read this story as David’s Machiavellian plan to eliminate any competition for the throne:

דוד מצא כאן שעת כושר להיפטר משרידי בית שאול שאפשר עוד היו עוללים לרכז סביבם תנועות מרי ומרד.

And this is how Yochi Brandes presents the story in The Secret Book of Kings. In fact, one of my complaints about The Secret Book of Kings is that it doesn’t give much time to this story; if you want to portray King David as a heartless monster, you couldn’t do better than this perek. But Brandes only gives two pages to it.

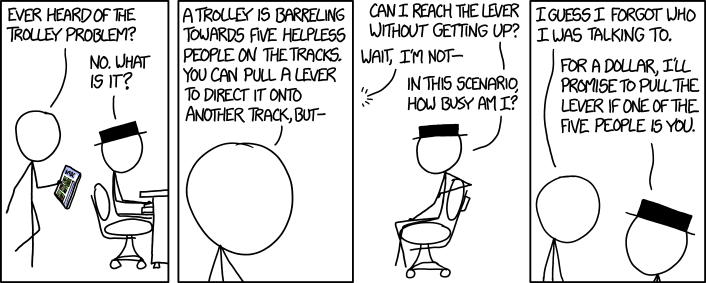

Be that as it may, I think it’s the wrong way to read this perek (as we will see). I would read it as the story of “David and the Trolley”.

The trolley problem is a thought experiment in ethics about a fictional scenario in which an onlooker has the choice to save 5 people in danger of being hit by a trolley, by diverting the trolley to kill just 1 person. The term is often used more loosely with regard to any choice that seemingly has a trade-off between what is good and what sacrifices are “acceptable,” if at all.

David will be faced with a choice, between a nation in the grip of a multi-year drought, and seven innocent men. There are wrong ways to approach the question:

But there is no right way. We will look at this perek with the approach of Emmanuel Levinas, in his Nine Talmudic Readings.

The [first] four Talmudic readings brought together in this volume represent the texts of talks delivered between 1963 and 1966 at the Colloquia of Jewish Intellectuals that the French section of the World Jewish Congress has organized in Paris every year since 1957.

…It is certain that, when discussing the right to eat or not to eat “an egg hatched on a holy day,” or payments owed for “damages caused by a wild ox,” the sages of the Talmud are discussing neither an egg nor an ox but are arguing about fundamental ideas without appearing to do so. It is true that one needs to have encountered an authentic Talmudic master to be sure of it.

Levinas was a French philosopher who emphasized our ethical responsibility to “the Other”; we cannot treat others as objects but must respect their own subjective identity. He actually did learn from a mysterious “authentic Talmudic master”:

Monsieur Chouchani…or “Shushani,” is the nickname of an otherwise anonymous and enigmatic Jewish teacher with students in the land of Israel, South America, post-World War II Europe, and elsewhere, including Emmanuel Levinas and Elie Wiesel.

But first we need to look at the story itself. It takes place בימי דוד; it doesn’t say ויהי אחרי כן. It is not part of the narrative sequence of the previous chapters. We have a similar expression in the beginnings of other books:

ויהי בימי שפט השפטים ויהי רעב בארץ; וילך איש מבית לחם יהודה לגור בשדי מואב הוא ואשתו ושני בניו׃

ויהי בימי אחשורוש; הוא אחשורוש המלך מהדו ועד כוש שבע ועשרים ומאה מדינה׃

This perek is its own little book, merged into the larger ספר שמואל.

When d0es this story take place? סדר עולם reads ספר שמואל chronologically, taking this story as happening after פרק כ, in the last years of David’s life. But it is hard to understand why Israel would be punished for Saul’s sin (which we will have to figure out), 30+ years later. So Rabbi Shulman assumes this takes place at the beginning of David’s reign, soon after Saul’s death (we still would have to understand why Saul himself wasn’t punished, and why the nation as a whole was punished). This is the opinion of the פרקי דרבי אליעזר:

ר׳ פנחס אומר: (שלש שנים) [אחרי שנה] שנהרג שאול ובניו בא רעב בימי דוד שלשה שנים שנה אחר שנה, שנ׳ ויהי רעב בימי דוד שלש שנים.

The bracketed text is in the hebrewbooks.com edition, which makes more sense to me.

But Abarbanel quotes this same פרקי דרבי אליעזר to support the סדר עולם:

אמר ר׳ פנחס: לאחר שלשים שנה שנהרג שאול ובניו…

There is internal evidence that this רעב took place before Avshalom’s rebellion; as David is running away from Jerusalem, he is cursed by שמעי בן גרא:

ה ובא המלך דוד עד בחורים; והנה משם איש יוצא ממשפחת בית שאול ושמו שמעי בן גרא יצא יצוא ומקלל׃ ו ויסקל באבנים את דוד ואת כל עבדי המלך דוד; וכל העם וכל הגברים מימינו ומשמאלו׃ ז וכה אמר שמעי בקללו; צא צא איש הדמים ואיש הבליעל׃ ח השיב עליך ה׳ כל דמי בית שאול אשר מלכת תחתו ויתן ה׳ את המלוכה ביד אבשלום בנך; והנך ברעתך כי איש דמים אתה׃

…יא ויאמר דוד אל אבישי ואל כל עבדיו הנה בני אשר יצא ממעי מבקש את נפשי; ואף כי עתה בן הימיני הנחו לו ויקלל כי אמר לו ה׳׃ יב אולי יראה ה׳ בעוני (בעיני); והשיב ה׳ לי טובה תחת קללתו היום הזה׃

Why would שמעי blame David for דמי בית שאול? And David doesn’t protest; he says שמעי is right. David wasn’t responsible for the death of Saul and his sons in battle; that was the Philistines. And Saul’s son Ishboshet was killed by his own men; David had the assassins publicly killed. But (spoiler alert!) in this story, שמואל ב פרק כא, David will tragically be directly responsible for the death of almost all Saul’s descendants.

I presented my opinion about the chronology of this רעב שלש שנים when we looked at שמואל ב פרק ט in Once Upon a Midnight Dreary. I will restate that here.

There is a paragraph break in our pasuk: ויבקש דוד את פני ה׳, then a break, then ויאמר ה׳. There was a gap between the time David started looking for a reason for the drought, and ה׳'s final answer.

ויבקש דוד את פני ה׳: מאי היא? אמר ריש לקיש ששאל באורים ותומים.

But the אורים ותומים don’t necessarily give explicit responses. ה׳ wants us to think about the consequences of our own behavior, not look for magical answers. We have multiple examples when the אורים ותומים are misleading:

יח ויקמו ויעלו בית אל וישאלו באלקים ויאמרו בני ישראל מי יעלה לנו בתחלה למלחמה עם בני בנימן; ויאמר ה׳ יהודה בתחלה׃ יט ויקומו בני ישראל בבקר; ויחנו על הגבעה׃…כא ויצאו בני בנימן מן הגבעה; וישחיתו בישראל ביום ההוא שנים ועשרים אלף איש ארצה׃

נביא כאן הסבר אשר ראיתיו בספר ”קול אליהו“ להגר״א מוילנא:

…כאשר עלי תמה על כך שחנה מתפללת בלחש, שאל באורים ותומים שלו לפשר הדבר ובלט האותיות ”ה“, ”כ“, ”ש“, ”ר“. כעת במקום לדון את חנה על ידי צירוף האותיות למילה ”כשרה“ הוא דן אותה לחובה על ידי צירוף האותיות למילה ”שכרה“.

And this seems to be another example of this: even when he gets an answer, it’s not clear: אל שאול ואל בית הדמים, “Look at Saul and the house of blood”, על אשר המית את הגבענים, “because he killed the Givonim”. What does that mean?

The gemara says that the process of looking for an answer was just that, a process:

ויהי רעב בימי דוד שלש שנים שנה אחר שנה: שנה ראשונה אמר להם: שמא עובדי (עבודת כוכבים) [עבודה זרה] יש בכם דכתיב (דברים יא:טז-יז) וַעֲבַדְתֶּם אֱלֹהִים אֲחֵרִים וְהִשְׁתַּחֲוִיתֶם לָהֶם׃ וְחָרָה אַף ה׳ בָּכֶם וְעָצַר אֶת הַשָּׁמַיִם וְלֹא יִהְיֶה מָטָר וגו׳? בדקו ולא מצאו.

שניה, אמר להם שמא עוברי עבירה יש בכם דכתיב (ירמיהו ג:ג) וַיִּמָּנְעוּ רְבִבִים וּמַלְקוֹשׁ לוֹא הָיָה וּמֵצַח אִשָּׁה זוֹנָה וגו׳? בדקו ולא מצאו.

שלישית, אמר להם: שמא פוסקי צדקה ברבים יש בכם ואין נותנין דכתיב (משלי כה:יד) נְשִׂיאִים וְרוּחַ וְגֶשֶׁם אָיִן אִישׁ מִתְהַלֵּל בְּמַתַּת שָׁקֶר? בדקו ולא מצאו.

אמר: אין הדבר תלוי אלא בי.

Rabbi Yehonasan Eybeschutz connected this to two other midrashim:

נאמר (דברי הימים א כב:יד): וְהִנֵּה בְעָנְיִי הֲכִינוֹתִי לְבֵית ה׳ זָהָב כִּכָּרִים מֵאָה אֶלֶף וגו׳. וכי עני מקדיש כל הככרים הללו של זהב וכסף? אלא ביום שהרג דוד את גלית השליכו עליו בנות ישראל כל הכסף והזהב הזה והקדישו לבית המקדש וכשבא רעב שלש שנים בקשו ממנו ישראל ליתן ולא רצה ליתן להם כלום. אמר לו הקדוש ברוך הוא: לא קבלת עליך להחיות בו נפשות? חייך שאין המקדש נבנה על ידך, אלא על ידי שלמה.

אמר רב אחא בר ביזנא אמר רבי שמעון חסידא: כנור היה תלוי למעלה ממטתו של דוד, וכיון שהגיע חצות לילה בא רוח צפונית ונושבת בו ומנגן מאליו, מיד היה עומד ועוסק בתורה עד שעלה עמוד השחר.

כיון שעלה עמוד השחר נכנסו חכמי ישראל אצלו, אמרו לו: אדונינו המלך, עמך ישראל צריכין פרנסה. אמר להם: לכו והתפרנסו זה מזה. אמרו לו: אין הקומץ משביע את הארי ואין הבור מתמלא מחוליתו. אמר להם: לכו ופשטו ידיכם בגדוד. מיד יועצים באחיתופל ונמלכין בסנהדרין, ושואלין באורים ותומים.

There was a point in time when, every morning, the leaders of the people would tell David, עמך ישראל צריכין פרנסה. And he would tell them: לכו ופשטו ידיכם בגדוד. Go out to war; plunder other nations. Don’t ask me for money. That point in time must have been a time of famine, a time of drought. And the only drought we know about is the one in our perek.

ענין הדבר כי ידוע מה שכתבו חז״ל כשעלה עמוד השחר נכנסו חכמי ישראל לדוד ”עמך ישראל צריכין פרנסה“. אמר ”פשטו ידיכם בגדוד“. ויש להבין מה ביקשו מדוד בזה באמרם ישראל צריכין פרנסה. אבל כבר מבואר במדרש: ”ואני בעניי הכינותי אלף אלפים דינרי זהב“. וכי יש לעני בישראל אלף אלפים דינרי זהב? אלא כשהרג לגלית השליכו עליו בנות ישראל כסף וזהב, והוא הפרישן לבנין בהמ״ק. וכשהיה רעב בארץ לא פתח אוצרות לכלכל עניים. ולכך קצף עליו השם ואמר טובה צדקה מבנין בית המקדש. ולכך אתה לא תבנה וגו׳.

ונראה כי חכמי ישראל הם שבקשו שיתן לעניים מהכסף וזהב ההוא, ולכך אמרו לו עמך ישראל צריכין פרנסה ופתח ותן. והוא מיאן לתת וצוה להלחם. וא״כ הרבה מלחמות רשות שנעשו בשביל פרנסת עניים, מה שהיה דוד יכול לתקן בפתחו אוצרות המוכנים לבית ה׳. וזהו פי׳ הפסוק ”דמים הרבה שפכת“ כי לָחַמְתָּ מלחמת רשות ולא היה הצורך כי היה לך לפרנס מן האוצרות ואת קמצת בשלך בצדקה. והעניים היו עטופים ברעב עד עבור ימי מלחמה ובין כך סבלו דוחק ולחץ. ולכך אתה לא תבנה הבית כי נבחר לה׳ צדקה מבנין בית, ולכך אמרתי דרך הלצה (ויקרא כו:ה-ו) וַאֲכַלְתֶּם לַחְמְכֶם לָשֹׂבַע [וִישַׁבְתֶּם לָבֶטַח בְּאַרְצְכֶם] וְנָתַתִּי שָׁלוֹם בָּאָרֶץ, כי כאשר לא היה לעם ישראל פרנסה פשטו ידיהם בגדוד. וז״א ואכלתם לחמכם לשובע שלא יחסר לחמכם א״כ אין צורך למלחמה ונתתי שלום בארץ. אכל נשמע מזה כי יותר טוב צדקה מבנין בית ה׳.

So Rabbi Eybeschutz claims the drought of our perek is contemporary with David’s מלחמות רשות, which are described in פרק ח. And this makes sense, since after the drought we will see (שמואל ב כא:ז) ויחמל המלך על מפיבשת בן יהונתן בן שאול; על שבעת ה׳ אשר בינתם בין דוד ובין יהונתן בן שאול, and after the wars of פרק ח the text has the story of מפיבשת in פרק ט: ויאמר המלך האפס עוד איש לבית שאול ואעשה עמו חסד אלקים…ויבא מפיבשת בן יהונתן בן שאול אל דוד.

So I would place the רעב שלש שנים in the period of time before the affair with Bat Sheva, when David is engaged in expanding his empire. He is focused not on his glory but on כבוד ה׳, planning for the future בית המקדש. But he is not thinking about what the people need. As he is seeking the possible spiritual causes for the drought, he narrows it down to a problem of פוסקי צדקה…ואין נותנין, then אין הדבר תלוי אלא בי. And he is given an answer: אל שאול ואל בית הדמים על אשר המית את הגבענים.

And how that connects to the problem of עמך ישראל צריכין פרנסה we will have to see.