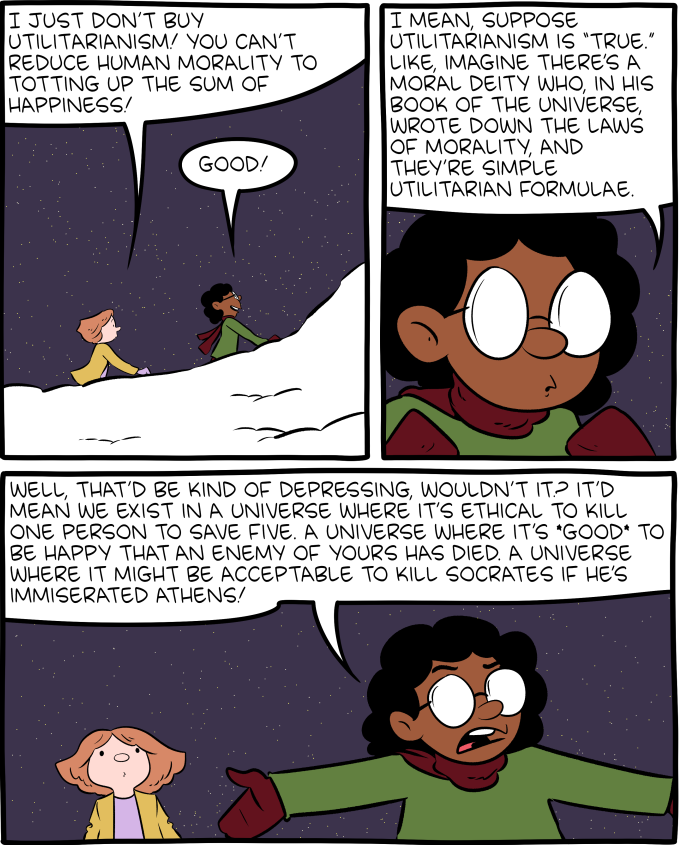

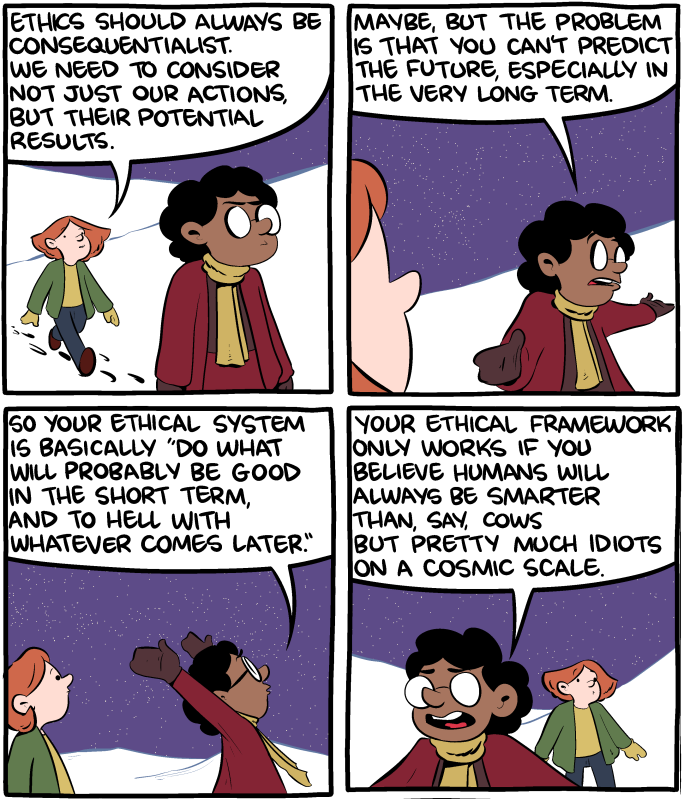

As we said last time, Shlomo’s real חכמה was in teaching מוסר, character development; how to be the best human being possible. ספר משלי is the compendium of his advice, and it's all short, almost trivial, verses. As Ramchal says in his introduction to מסילת ישרים: {:he} >החבור הזה לא חברתיו ללמד לבני האדם את אשר לא ידעו, אלא להזכירם את הידוע להם כבר ומפרסם אצלם פרסום גדול. כי לא תמצא ברוב דברי, אלא דברים שרב בני האדם יודעים אותם ולא מסתפקים בהם כלל. --מסילת ישרים, הקדמה But learning and re-learning these things is still critical. {:he} >ותראה, אם תתבונן בהוה ברוב העולם, כי רב אנשי השכל המהיר והפקחים החריפים ישימו רב התבוננם והסתכלותם בדקות החכמות ועמק העיונים איש איש כפי נטית שכלו וחשקו הטבעי. כי יש שיטרחו מאד במחקר הבריאה והטבע, ואחרים יתנו כל עיונם לתכונה ולהנדסה, ואחרים למלאכות. ואחרים יכנסו יותר אל הקדש, דהינו, למוד התורה הקדושה. מהם בפלפולי ההלכות, מהם במדרשים, מהם בפסקי הדינים. > אך מעטים יהיו מן המין הזה אשר יקבעו עיון ולמוד על עניני שלמות העבודה, על האהבה, על היראה, על הדבקות, ועל כל שאר חלקי החסידות. ולא מפני שאין דברים אלה עקרים אצלם, כי אם תשאל להם, כל אחד יאמר שזהו העקר הגדול...אך מה שלא ירבו לעין עליו הוא מפני רב פרסום הדברים ופשיטותם אצלם שלא יראה להם צרך להוציא בעיונם זמן רב. --מסילת ישרים, הקדמה And the implication of these terse apodictic statements is that there is a single correct answer to every question in human relationships. It's clearly not literally true. >Two neighbors were fighting over a financial dispute. They couldn’t reach an agreement, so they took their case to the local rabbi. The rabbi heard the first litigant’s case, nodded his head and said, “You’re right.” > The second litigant then stated his case. The rabbi heard him out, nodded again and said, “You’re also right.” > The rabbi’s attendant, who had been standing by this whole time, was justifiably confused. “But, rebbe,” he asked, “how can they both be right?” > The rav thought about this for a moment before responding, “You’re right, too!” --Rabbi Jack Abramowitz, [_You’re Right, Too_](https://www.ou.org/life/inspiration/youre-right-too/) But this approach of משלי is an inherent part of its philosophy. It is one of three books of תנ״ך that have their own unique טעמים: איוב, משלי and תהילים; together they are called "ספרי אמ״ת". We talked about this when we began studying תהילים, back in <//Smooth Rock>. Calling them books of "אמת" is clearly significant, but what do they have in common that separates them from other "philosophical" books like קוהלת? My answer is that these books are the ones that deal, as their major focus, with the fundamental question of Jewish philosophy, צדיק ורע לו--why do bad things happen to good people; the problem of theodicy. There are three classical Jewish answers, given in these three books: - ה׳'s wisdom and plan is too deep for human beings to understand. He is good, but in our limited perspective we may not comprehend His goodness. This is expressed in איוב. - The evil that befalls the good and the reward of the wicked are just; everything that happens to a person is deserved. Bad things that happen to good people is because of the (possibly minor) sins they have committed. This is expressed in משלי. - גם זו לטובה. What seems to be a bad thing will be seen to actually to have been for a person's benefit, not in some vague unknowable sense, but within the person's own experience. This is the approach of תהילים. We need to emphasize that none of these are *answers* to the question of צדיק ורע לו, they are *approaches*. There is no answer, and, as human beings, we have to accept that. Not even Moshe could get that answer from הקב״ה. {:he} >בקש להודיעו דרכיו של הקדוש ברוך הוא, ונתן לו, שנאמר (שמות לג:יג): הוֹדִעֵנִי נָא אֶת דְּרָכֶךָ. אמר לפניו: רבונו של עולם! מפני מה יש צדיק וטוב לו, ויש צדיק ורע לו, יש רשע וטוב לו, ויש רשע ורע לו?...שתים נתנו לו [בקשות] ואחת לא נתנו לו [הבקשה הזאת של צדיק ורע לו], שנאמר (שמות לג:יט): וְחַנֹּתִי אֶת אֲשֶׁר אָחֹן— אף על פי שאינו הגון, וְרִחַמְתִּי אֶת אֲשֶׁר אֲרַחֵם—אף על פי שאינו הגון. --ברכות ז,א But to live our lives we need ways of thinking about theodicy, and one of those (that will be appropriate for some people, in some situations) is ספר משלי: bad things *don't* happen to good people. Follow this advice and all will go well. {:he} >אין יסורין בלא עון. --שבת נה,א {:he} >ספר משלי הוא ספר הבטחון. בטחון בא־ל ובדרך ישר באדם: ארץ ניתנה ביד צדיק...אין לו לאדם אלא ללכת בדרך תום, לשמור מוסר, לשחר את הטוב, לירא את השם, להיות חרוץ במעשה--וארץ ניתנה לו. דרכו נכונה לפניו ופעלו שלם לו ולזרעו אחריו. יש עין צופיה...ויש גמול אמת, לצדיק ולרשע...ויש סדר מוסרי בעולם (משלי י:ל): צַדִּיק לְעוֹלָם בַּל יִמּוֹט וּרְשָׁעִים לֹא יִשְׁכְּנוּ אָרֶץ...מתוך האמונה השלימה השולטת כאן, שהצדיק הוא העושה מצוות החכמה, המטה לבו לתבונה למען ילך "בדרך טובים", עולה כאן ממילא גם השוואה המיוחדת, שבעצם הצדיק האמיתי הוא גם החכם האמיתי, ואילו הרשע הוא גם אויל ועצל...האויל כאן הוא הניגוד לצדיק והוא עומד כאן במקום הרשע...מעשי החכם הם מעשי צדיק, כשם שלהפך--דרך האויל הוא עצם דרך הרשע (משלי יג:יט): וְתוֹעֲבַת כְּסִילִים סוּר מֵרָע. הוי אומר: החכמה מראה דרך ישר לאדם והיא דרך ההצלחה. מהן מידותיה של דרך ישרה זו, אותן מלמד ספר משלי. --יהושע מאיר גרינץ, [_על ספר משלי_](https://www.daat.ac.il/he-il/tanach/iyunim/ktuvim/mishlay/mishley-all/mishley-grinits.htm) ---- It is instructive to compare משלי to Shlomo's other Book of Wisdom, ספר קהלת. קהלת is not about theodicy; it is about existentialism. What is the point of our lives if we are going to die? The universe existed before we existed, and will continue to exist long after we are gone. The book goes through twelve chapters of debate but reaches a conclusion in its penultimate verse: {:he} >סוף דבר הכל נשמע; את האלקים ירא ואת מצותיו שמור כי זה כל האדם׃ --קהלת יב:יג The ספרי אמ״ת *start* from that conclusion. Our חכמה, understanding of how the world works and how it ought to work, starts from יראת ה׳. {:he} >תחלת חכמה יראת ה׳; ודעת קדשים בינה׃ --משלי ט:י {:he} >ויאמר לאדם הן יראת ה׳ היא חכמה; וסור מרע בינה׃ --איוב כח:כח {:he} >ראשית חכמה יראת ה׳ שכל טוב לכל עשיהם; תהלתו עמדת לעד׃ --תהילים קיא:י ספר קהלת is the prerequisite to ספר משלי. We have to start from a position of יראת ה׳ before we can learn מוסר. Ethical rules have to be tied to the acknowledgement of a higher power, because human brains aren't smart enough to understand the interactions of more than a few other human beings or the consequences of our actions beyond a short time. >Dunbar's number is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships—relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person. --Wikipedia, [_Dunbar's number_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunbar's_number) Even the wisest of all men had to say (קהלת ז:כג) אמרתי אחכמה והיא רחוקה ממני. If we try to create absolute rules for evaluating human actions, we inevitably end up justifying immoral behavior. One example is utilitarianism, that we can quanitate the value of a life, and so having more miserable people is better than fewer happy people. >[T]he “repugnant conclusion”: the idea that adding more humans with good lives is always valuable, and so we should aim for the biggest population we can support, even if that means average happiness goes down. The idea that we should try to create a world teeming with miserable people whose lives are barely worth living strikes most philosophers as, indeed, repugnant. --Dylan Matthews, [_The case for adding more and more people to the Earth_](https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/6/5/18617894/repugnant-conclusion-population-growth-philosophy)  --First three panels from https://www.smbc-comics.com/comic/utilitarian (click through for the punchline, such as it is) So we have a problem, from משלי's point of view. Good things happen to good people, but we're not smart enough to be good people.  --SMBC, [_Consequentialism_](https://www.smbc-comics.com/comic/consequentialism), abridged The other option for developing ethics is deontological ethics. >In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek: δέον, “obligation, duty” + λόγος, “study”) is the normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules and principles, rather than based on the consequences of the action. It is sometimes described as duty-, obligation-, or rule-based ethics. --Wikipedia, [_Deontology_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deontology) This sounds appealing to the halachic mind, since the rules are divinely determined. But applying rules without thinking about consequences also ends up immoral. >Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron's cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience. They may be more likely to go to Heaven yet at the same time likelier to make a Hell of earth. --C.S. Lewis, [God in the Dock: Essays on Theology](https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/526469-of-all-tyrannies-a-tyranny-sincerely-exercised-for-the-good) So we end up with what is called virtue ethics: be a good person and your actions will be good. Practice doing the right thing in cases that aren't hard, and you will develop your moral intuition for the actual hard decision. Aristotle called this "phronesis". >Phronesis...is a type of wisdom or intelligence relevant to practical action. It implies both good judgment and excellence of character and habits...In Aristotelian ethics, the concept was distinguished from other words for wisdom and intellectual virtues...because of its practical character. --Wikipedia, [_Phronesis_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phronesis) >What has been said is confirmed by the fact that while young men become geometricians and mathematicians and wise in matters like these, it is thought that a young man of practical wisdom [phronesis] cannot be found. The cause is that such wisdom is concerned not only with universals but with particulars, which become familiar from experience, but a young man has no experience, for it is length of time that gives experience. -- Aristotle, [_The Nicomachean Ethics_ VI:8](https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.6.vi.html) I will use the words ethics and morality to refer to two different things (I think Rav Lichtenstein defined them this way, but I can't find the source). Others use those words differently, but the concepts need to be destinguished. "Ethics" is a set of rules of behavior that can be thought about and reasoned with. "Morality" refers to a person's intuition about what is right and wrong. Both refer to the rules of interpersonal relationships; ethics are of the mind and morals are of the heart. Pure ethics is impossible; human minds are too limited. However, our moral intuition is determined not by some inherent moral-o-meter that we are born with, but by the things we see other people doing. We discussed this in <//Let Me Count the Ways ס>. >...Maimonides holds that moral claims are never open to rational argument or demonstration. They are "propositions which are known and require no proof for their truth "...[M]oral rules are true only in the sense that in a well-ordered society they are accepted and not subject to doubt. They are "conventions..." Society, properly governed, forms our tastes and patterns of response in such a way that we have no doubt about such matters. However, this is not in any respect a matter of rational certainty or demonstrative evidence. --Marvin Fox, [_Interpreting Maimonides_](https://www.amazon.com/Interpreting-Maimonides-Methodology-Metaphysics-Philosophy/dp/0226259420) We are social primates, and "right" means "what everyone does". But, our brains don’t understand “fiction”. Observing something over and over in any context makes it normal and therefore moral. That is what makes TV, movies and videos so powerful and so potentially dangerous. What we see is what is right. So the first step in achieving חכמה, phronesis, is to choose the right stories. The Torah starts with בראשית, the stories of the אבות, because we need more than black and white rules, halacha, in our interpersonal relationships. בראשית is called ספר הישר. {:he} >(יהושוע י:יג) וַיִּדֹּם הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ וְיָרֵחַ עָמָד עַד יִקֹּם גּוֹי אֹיְבָיו הֲלֹא הִיא כְתוּבָה עַל סֵפֶר הַיָּשָׁר. מאי ספר הישר? א״ר חייא בר אבא א״ר יוחנן זה ספר אברהם יצחק ויעקב שנקראו ישרים שנאמר (במדבר כג:י) תָּמֹת נַפְשִׁי מוֹת יְשָׁרִים. --עבודה זרה כה,א {:he} >וכן הרבה למדנו מהליכות האבות בדרך ארץ מה ששייך לקיום העולם, המיוחד לזה הספר שהוא ספר הבריאה. ומשום הכי נקרא כמו כן ספר הישר על מעשה אבות בזה הפרט. --חומש העמק דבר, פתיחה לספר בראשית ---- So Shlomo, trying to teach his חכמה, does not give a list of algorithms. He gives short, memorable statements, parables, metaphors aimed at engaging both our minds and our hearts. So we come back to יראת ה׳ as the sense of distance from Divine Authority. We listen even though we cannot fully understand. And our imperfect understanding means that our משלים, apothegms, need to be משלים, parables.