We are at the end of פרק יג; it’s not really the end of anything as there is no paragraph break before פרק יד. The next paragrapah break is in the middle of פרק טו. These are all short proverbs about personal character development and interpersonal relationships, but the next one seems different:

רב אכל ניר ראשים; ויש נספה בלא משפט׃

The language is very difficult: ניר is a furrow in a plowed field, so רב אכל ניר ראשים means “lots of food…furrow of the poor”, and נספה is from לספות, to be wiped out, from סוף, end:

ויגש אברהם ויאמר; האף תספה צדיק עם רשע׃

So ויש נספה בלא משפט means “and there are those who are wiped out without justice”. Putting them together, this pasuk seems to be a complaint about צדיק ורע לו: the poor toil to produce food for others, but then unjustly suffer.

יש מי אשר נאסף מכל העולם בלא משפט מות כי לא עשה דבר אשר יומת בעבורו ונתפס הוא בעון אחר.

משיב שכן ראינו במציאות שרב אוכל בא ע״י ניר ראשים, שדלת העם הרשים נרים את האדמה להסיר משם הקוצים והדרדרים, שזה עבודה קשה יעשו אותה הרשים ועל ידם בא אוכל רב, ובכ״ז יש מן הרשים שנספה בלא משפט, שימות ברעב ואין אוכל למו, הגם שכל האוכל בא על ידי עבודתם, וכן הגם שרב אוכל בא ע״י הצדיקים וזכותם שמסירים את הקוצים המעכבים את השפע, בכ״ז ימצא ביניהם שנספה ברעב.

The question of theodicy goes back to Avraham himself: האף תספה צדיק עם רשע, and our pasuk clearly alludes to it, but it’s not typical for ספר משלי. It’s more a question for ספר קוהלת.

את הכל ראיתי בימי הבלי; יש צדיק אבד בצדקו ויש רשע מאריך ברעתו׃

So Rashi softens the pasuk, translating בלא משפט to refer to the person who acts unjustly:

רב־אכל ניר ראשים: הרבה תבואה באה לעולם על ידי ניר אנשים דלים…

ויש נספה: ויש הרבה מהם שהם כלים מן העולם בשביל לא משפט שאינן נוהגין כשורה, ולענין התבואה יש תבואה לוקה בשביל בעליה שאינו מוציא מעשרותיה ומתנות עניים כמשפט.

Which gives the overall sense of “you may work hard and be successful, but it won’t last if you are unjust”. That’s more in line with משלי, but Rashi goes further and takes the entire pasuk metaphorically:

כלומר: הרבה תורה יוצאה על ידי תלמידים, שרבותיהם למדין מהם מתוך פלפולם שמפלפלים בהלכה.

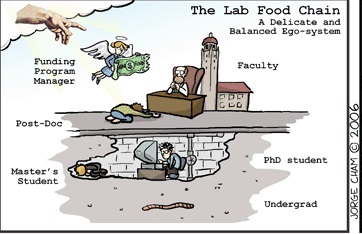

The ראשים, the poor whose furrows produce all the food, are the students. I’ve been a grad student; I know what that means.

But in the Torah model, it’s not about grant money. It’s about intellectual development and it is through teaching that תלמידי חכמים sharpen their ideas.

למה נמשלו דברי תורה כעץ, שנאמר (משלי ג:יח): עֵץ חַיִּים הִיא לַמַּחֲזִיקִים בָּהּ? לומר לך: מה עץ קטן מדליק את הגדול, אף תלמידי חכמים קטנים מחדדים את הגדולים.

והיינו דאמר רבי חנינא: הרבה למדתי מרבותי, ומחבירי יותר מרבותי, ומתלמידי יותר מכולן.

And so the second half, יש נספה בלא משפט, is about students and teachers as well. We need not just intellectual rigor but משפט. Without that, our students will be destroyed.

אמרו: שנים עשר אלף זוגים תלמידים היו לו לרבי עקיבא מגבת עד אנטיפרס, וכולן מתו בפרק אחד, מפני שלא נהגו כבוד זה לזה. והיה העולם שמם, עד שבא רבי עקיבא אצל רבותינו שבדרום ושנאה להם: רבי מאיר, ורבי יהודה, ורבי יוסי, ורבי שמעון, ורבי אלעזר בן שמוע, והם הם העמידו תורה אותה שעה.

מפני שלא נהגו כבוד זה לזה כו׳: ולא חש כל אחד מהם על כבוד תורה של חבירו.

We discussed this in Know-It-All:

אמר רבי אבא אמר שמואל: שלש שנים נחלקו בית שמאי ובית הלל, הללו אומרים: הלכה כמותנו, והללו אומרים: הלכה כמותנו. יצאה בת קול ואמרה: אלו ואלו דברי אלקים חיים הן; והלכה כבית הלל.

וכי מאחר שאלו ואלו דברי אלקים חיים, מפני מה זכו בית הלל לקבוע הלכה כמותן? מפני שנוחין ועלובין היו, ושונין דבריהן ודברי בית שמאי, ולא עוד אלא שמקדימין דברי בית שמאי לדבריהן.

Here, Beis Hillel’s humility enhanced their understanding…Egos want to be right. They want to hear their own opinions. Overcoming this to hear another viewpoint expands the mind. Beis Hillel first learned Beis Shammai’s ideas to their depths. They then returned to what they had originally thought. But now their position was much stronger. It incorporated the understanding they gained from Beis Shammai. Beis Hillel was now on Beis Shammai’s shoulders, so to speak.

To become wise, it is not enough to work your own metaphoric field. You have to be willing to accept other’s work as well.

Shlomo then continues with the most important sort of student: children. The Torah makes the point that our children are our students:

ולמדתם אתם את בניכם לדבר בם; בשבתך בביתך ובלכתך בדרך ובשכבך ובקומך׃

So Shlomo famously says:

חושך שבטו שונא בנו; ואהבו שחרו מוסר׃

חושך שבטו: סופו ששונא את בנו, שרואהו בסופו יוצא לתרבות רעה.

שחרו, from שחר, “morning”, means both “everyday” and “from the beginning”.

שחרו מוסר: תמיד לבקרים מיסרהו.

שחרו: עניינו ימי הילדות שהוא בתחילת הימים.

What I am going to say here comes from Rabbi Frand’s shiur on Chinuch HaBanim. I had a cassette tape of that lecture (not that anyone remembers cassette tapes) when I was living in Baltimore, and I owned a car, which is a mistake when living in Baltimore. When my car was broken into, they stole some loose change and that tape. I imagine that there is some punk out there whose life was changed when he listened to that tape and is now an upstanding parent in the Baltimore community. I can only hope.

Every Jewish parent knows the verse חושך שבטו שונא בנו, which is commonly translated as, “Spare the rod and spoil the child,” but more literally means “One who spares the rod hates the child”.

I actually looked up the source of the mistranslation and immediately regretted it. It’s from a 17th century ribald poem that was a satire of Don Quixote, and the quote is about spanking as a “romantic” activity.

Love is a boy by poets styl’d; Then spare the rod, and spoil the child… Why may not whipping have as good A grace? perform’d in time and mood, With comely movement, and by art, Raise passion in a lady’s heart?

So I won’t mention “Spare the rod and spoil the child” (how’s that for paraleipsis?) but will focus on חושך שבטו שונא בנו.

From this verse, we might think that the Torah advocates corporal punishment—a good smack every once in a while. But that is not necessarily the case. If if were, then the verse should end, “And one who loves him will multiply his blows.” But that is not so. Rather the verse ends, “And one who loves him offers him mussar.” The child should know that there is a rod hanging on the wall, but the Torah tells us that there are plenty of other ways to punish the child rather than with the rod.

But this is ספר משלי, the book of metaphors, so the rod is metaphoric. In תהילים, the שבט is the symbol of negative reinforcement. David is comforted by it, as it means that ה׳ still cares about him:

גם כי אלך בגיא צלמות לא אירא רע כי אתה עמדי; שבטך ומשענתך המה ינחמני׃

And Zecharia talks about a מקל called נעם.

ו כי לא אחמול עוד על ישבי הארץ נאם ה׳; והנה אנכי ממציא את האדם איש ביד רעהו וביד מלכו וכתתו את הארץ ולא אציל מידם׃ ז וארעה את צאן ההרגה לכן עניי הצאן; ואקח לי שני מקלות לאחד קראתי נעם ולאחד קראתי חבלים וארעה את הצאן׃

Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe explains that positive reinforcement is a perfect example of “pleasantness” [נעם] and when someone withholds a compliment, that, too, can be considered a rod. So can a sharp look or an expression of disappoinment. There are plenty of rods other than hitting, and Shlomo Hamelech is talking about these and not physical abuse.

A child requires discipline; he needs and wants to know that there are limits. But hitting is rarely the most effective way of bringing home that message.

The goal of the שבט is מוסר, not punishment.

Shlomo Hamelech also teaches us that “the wounds of one who loves are effective” [(משלי כז:ו) נֶאֱמָנִים פִּצְעֵי אוֹהֵב] But the wounds must be administered by one who loves and is perceived as such. Even when you punish your child, he must always realize that this is punishment meted out by one who loves him and seeks his well-being, not one who, G-d forbid, hates him.

The end point of raising children is not to have children; it is to raise adults. Rav Hirsch has an amazing interpretation of פרו ורבו (generally translated as “be fruitful and multiply”):

ויברך אתם אלקים ויאמר להם אלקים פרו ורבו ומלאו את הארץ וכבשה; ורדו בדגת הים ובעוף השמים ובכל חיה הרמשת על הארץ׃

The meaning of forming, educating which is innate in the root רבה is found in (בראשית כא:כ) רֹבֶה קַשָּׁת…תרבות…and not unlikely even the name רב and רבי for teacher come from the same conception…Only by taking over רְבוּ does פְּרוּ attain its high, moral importance for the building of mankind.

Children are like arrows. All we do is aim them and fire.

א שיר המעלות לשלמה… ד כחצים ביד גבור כן בני הנעורים׃ ה אשרי הגבר אשר מלא את אשפתו מהם; לא יבשו כי ידברו את אויבים בשער׃

The next pasuk is almost too simple:

צדיק אכל לשבע נפשו; ובטן רשעים תחסר׃

צדיק אוכל לשבע נפשו: הצדיק לא יאכל למלא בטנו, רק לשובע נפשו כדי הסיפוק לא מותרות, גם ירמוז שאוכל לשובע נפשו הרוחניית, כפי הצריך רק להחיות נפשו.

אבל רשעים שאוכלים למלא בטנם, בטנם תחסר תמיד, כי כל שיש לו הוא מתאוה יותר ואין קץ לתאותו.

It’s a statement about greed and human nature.

אהב כסף לא ישבע כסף; ומי אהב בהמון לא תבואה גם זה הבל׃

And Shlomo acknowledges that this is human nature. ה׳ made us that way, to always want more than we have.

ראיתי את הענין אשר נתן אלקים לבני האדם לענות בו׃

ראיתי את הענין: אמר רבי איבו זה שפוטו של ממון, דאמר רבי יודן בשם רבי איבו אין אדם יוצא מן העולם וחצי תאותו בידו, אלא אם אית ליה מאה בעי דיעבדון תרתי מאה, ומאן דאית ליה תרתי מאה בעי דיעבדון ארבעה.

Hedonic adaptation, sometimes referred to as the “hedonic treadmill,” is a psychological process. It refers to the notion that the feelings you experience, as a result of positive or negative life events, essentially return to a relatively stable, baseline level of happiness after those events occur.

In the example of making a new purchase, the initial surge of happiness you feel fades as the newness wears off and you adapt to a new “normal.” Eventually, you return to your baseline level of contentment.

But Rashi says there’s a more subtle point: Shlomo is not talking just about mundane wealth.

אהב כסף לא ישבע כסף: אוהב מצות לא ישבע מהם.

The desire for more becomes a goal in itself. Even the אוהב מצות becomes a game, getting more mitzvah points. We lose the connection to ה׳ if we focus on getting every new חומרה and מנהג. The midrash connects this to our pasuk:

(במדבר כח:ב) תשמרו להקריב לי במועדו: זה שאמר הכתוב: צַדִּיק אֹכֵל לְשׂבַע נַפְשׁוֹ.

Be careful to bring the requisite קרבן במועדו, at its appointed time. There’s no benefit to going overboard. And for ספר משלי, the same is true of learning wisdom, even the wisdom of Torah.

אמר רב יהודה אמר רב מאי דכתיב (ירמיהו ט:יא) מִי הָאִישׁ הֶחָכָם וְיָבֵן אֶת זֹאת […עַל מָה אָבְדָה הָאָרֶץ]?…(ירמיהו ט:יב) וַיֹּאמֶר ה׳ עַל עָזְבָם אֶת תּוֹרָתִי וגו׳. היינו לא שמעו בקולי היינו לא הלכו בה?! אמר רב יהודה אמר רב שאין מברכין בתורה תחלה.

…אף אם היו מברכין בפה, מכל מקום דבר הזה שהוא נתינת התורה צריך לברך ה׳ יתברך בכל לבו, ובזה יש לו האהבה הגמורה אל ה׳ יתברך…ועוד כי התלמיד חכם לבו דבק אל התורה כי חביבה התורה אל לומדיה, ובשביל אהבתם לתורה דבר זה מסלק אהבת המקום בשעה זאת שבאים ללמוד, כי כאשר באים ללמוד תורה ואהבתם אל התורה אין בלימוד שלהם האהבה אל ה׳ יתברך במה שנתן התורה, כי אין האהבה לשנים…

In a little bit of fortuitous השגחה פרטית, I caught up on Yitzchok Adlerstein’s posts on Cross Currents and he cited this Maharal and Professor Eli Hirsch’s article in Tablet:

You have to understand the mad passion with which we in the yeshiva loved the Torah, which was understood to include all of the canonical Talmudic commentary coming down through the ages. G-d was for us a mystery, an abstraction of smoke and mirrors, a blank something-we-know-not-what that was somehow responsible for the Torah. If we claimed to love G-d, this love was only a shadow of what we truly loved, the Torah, G-d’s stupendous gift to us.

Now, in משלי the focus in not on דבקות to ה׳ but on דבקות to our fellow human beings, but the message is the same: צדיק אכל לשבע נפשו. It’s not about scoring points.