Thank you to everyone who participated in getting me Rabbi Fohrman’s new book, Genesis: A Parsha Companion. I just got it, so I figure I have to use it for this week’s parasha class. His chapter on לך לך is all about chiasmus, which I assume most of those listening to this shiur know about. But I’m going to talk about it.

Chiasmus is one of those words that sounds fancy because it comes from Greek, but it just means “X-ing”, “marking with an X”, from the Greek letter chi, χ. There’s a similar word in תנ״ך:

ויאמר ה׳ אלו עבר בתוך העיר בתוך ירושלם; והתוית תו על מצחות האנשים הנאנחים והנאנקים על כל התועבות הנעשות בתוכה׃

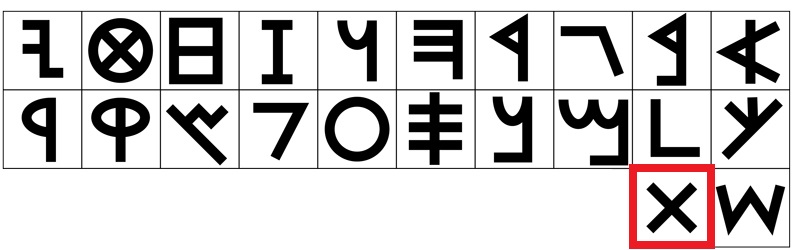

In ancient Hebrew (כתב עברית) the letter ת was just an “𐤕”:

(Thanks to Mitch Wolf for pointing this out to me)

So what does that have to do with תנ״ך? Biblical poetry is all about parallelism, and sometimes the two parallel parts are in fact anti-parallel; the themes are repeated in reverse order. So, to diagram it, you have to write an “X”:

There’s a specific form of chiasmus called antimetabole, where the exact words are repeated in reverse order, as (בראשית ט:ו) שפך דם האדם, באדם דמו ישפך.

It’s not clear how important it is for understanding Biblical poetry; as James Kugel says, it may only be a way of keeping the verse from being too monotonous:

Differentiation is also behind the frequent use of chiastic word order…Of course, chiasmus is a well-known trope of Greek and Latin literature, and had been all too readily assimilated to such biblical uses…since the days of the Church Fathers…But chiasmus in Hebrew, while it undeniably provides the same aesthetic pleasure as in European languages, ought rightly not to be separated from the context of parallelism itself. That is, where it appears in Greek or Latin more or less “out of the blue”, in Hebrew it is truly a concomitant of the binary structure of parallelistic sentences.

So there are a lot problems with looking for chiasms in תנ״ך. It isn’t a Jewish idea; the classical מפרשים aren’t interested in poetic style and look at the words, not the arrangement of them. It has no deeper meaning (or at least no one has proposed a deeper meaning), beyond sounding nice: “When the going gets tough, the tough get going”. And when the term is used in ”modern“ תנ״ך studies, it means something much broader. It’s not the structure of individual verses, but the arrangement of entire paragraphs and sections of תנ״ך that have this ”antiparallel" structure.

כבר לפני כמאתיים שנה עמדו חוקרים על כך שאם הפסוק הבודד או הנאום הקצר מעוצבים במבנה כיאסטי, הרי שייתכן שגם סיפורים שלמים או אף ספרים שלמים מעוצבים במבנה מאורגן שכזה. נטייה זו נקשרת עם שמותם של גֶ׳בּ, בּוֹיס ובּוֹלִינגֶר שפרסמו את מחקריהם במחצית הראשונה של המאה ה-19. מאז ועד היום רבו הכותבים והפרשנים שהציעו מבנים כיאסטיים או קונצנטריים לפרשיות חוק, לנבואות ולמזמורים, ולסיפורים שונים.

He gives the example of מגילת אסתר:

A Introduction—the royal power of Achashverosh (1:1)

B Two Persian feasts: one for the provincial ministers (180 days), and a special second one for the residents of Shushan (7 days) (Ch. 1)

C Esther comes before the king and is chosen as queen (Ch. 2)

D Describing the greatness of Haman: “King Achashverosh advanced Haman ben Hammedata the Agagite and he elevated him” (3:1-2).

E Casting the lots: war on the 13th of Adar (3:3-7).

F Giving the ring to Haman; Haman’s letters; Mordekhai tears his garments; Esther and the Jews fast (3:8-4:17).

G Esther’s first feast: Haman comes out “happy and of good cheer” (5:1-8).

H Haman consults his kinsmen: optimism (5:9-14).

I The king’s insomnia and the journey on the royal horse (Ch. 6).

H1 Haman consults his kinsmen: pessimism (6:12-14).

G1 Esther’s second feast: Haman is hanged (Ch. 7).

F1 Giving the ring to Mordekhai; Mordekhai’s letters; Mordekhai is clothed in royal garments; the Jews feast (Ch. 8).

E1 The war on the 13th of Adar (9:1-2).

D1 Describing the greatness of Mordekhai and the Jews, who attack their enemies: “All of the ministers of the provinces… were elevating the Jews… for the man Mordekhai was advancing in prominence” (9:3-11).

C1 Esther comes to the king and asks for another day of war in Shushan (9:12-16).

B1 Two Jewish feasts: one for the Jews of all the provinces (the 14th of Adar) and a special second one for Jews of Shushan (the 15th of Adar) (9:17-32).

A1 Conclusion—the royal power of Achashverosh (Ch. 10).

But the problem remains: it’s not a Jewish approach to תנ״ך; there’s no hint of this in any traditional source. Why do it?

Part of the answer is that it is rewarding; it feels like you’re discovering new layers of Torah that no one has ever seen before. And you can propose deep meaning to the structure: it represents a “bullseye” as Rabbi Fohrman puts it, drawing our attention to the center of the X. But it has a “Bible codes” feeling to it; am I reading too much into the text? Would I find the same structure in a Berenstain Bears book?

I think we need to find this kind of structure because there is an obvious problem with the text of the Torah: it doesn’t seem to have much structure. Things get repeated, stories seem to happen multiple times, laws come up in contradictory ways.

The traditional answer is to not worry about it. The Torah will leave some details out and fill them in elsewhere.

דברי תורה עניים במקומן ועשירים במקום אחר.

The academic approach is to say that the text we have in front of us is an amalgamation of older fragments of stories, each incomplete retellings of older tales. This is the Documentary Hypothesis. They were assembled by a “redactor” who couldn’t decide which one to include, so they threw everything together. As believing Jews, this is anathema when applied to the Torah, and even for נ״ך, it misses the point. What we have is a single text, and assuming the redactor was drunk makes reading “the Bible as literature” meaningless.

…the incredible abuse of this resource [investigation of a text’s sources] for over two hundred years of frenzied digging into the Bible’s genesis, so senseless as to elicit either laughter or tears. Rarely has there been such a futile expense of spirit in a noble cause; rarely have such grandiose theories of origination been built and revised and and pitted against one another on the evidential equivalent of the head of a pin; rarely have so many worked so long and so hard with so little to show for their trouble.

Looking at the structure of the narratives of Torah started in modern times because it only became relevant in modern times. We look for answers to the questions that we are asking.

כן, בבואנו ללמוד תורה וללמדה, שומה עלינו להיות ערים לרחשי לבות בני דורנו, ותוך כדי לימוד תורה והוראתה לנסות לסלק את הקשיים ותה המוקשים העומדים בדרכנו ובדרכם להבנת התורה על טהרת הקודש כתורת חיים. אל לנו לעסוק בשאלות אשר עבר זמנן, ובודאי שאל לנו לעורר בעיות (מזמנים עברו) כדי לפתור אותן (בימינו אנו)! ומעשה שהיה בי כך היה: היתה פנייה אלי ”לערוך“ מחדש את פירושו של הרב פרופ׳ ד. צ. הופמן זצ״ל ”ולהתאימו“ לקורא בן זמננו ,וזאת כפירוש חדש על התורה לדור הצעיר. תשובתי הייתה שאם ברצוננו להיות נאמנים לדרכו של הרב הופמן זצ״ל, אסור לעשות כך! כשם שהרב הופמן לא התמודד עם בעיות דורו של הרמב״ם ,אלא עם בעיות לימוד תורה באירופה במאה הקודמת, כך לא לנו לעורר לתחיה את בעיות דורו של הרב הופמן אשר מזמן שבקו חי, כדי לטפל בהם מחדש .במקום זה יש לטפל בשאלות המטרידות את לומד התורה בימינו אנו.

מעז עסקתי בלימוד תורה והוראתה, חש אנכי כי השאלה הגדולה והמרכזית המטרידה את הלומד החכם והנבון הוא: ”מדוע הכל הפוך כל כך“ (?!): מדוע התורה מחלקת סוגיא אחת (כגון עבד עברי) לשלושה מקומות שונים מרוחקים זה מזה? נכון שניתן ללמוד…מן האחד אל השני אבל מדוע ”קצת פה וקצת שם“…בעוד ניתן ללמוד את הכל ”בצורה מסודרת“ במקום אחד!

Rav Copperman dedicates his 2-volume magnum opus to this question, but the analysis of chiasmus is one answer. The repetition creates a literary structure that gives meaning to the text as a whole, drawing our attention to the central point around which the entire narrative revolves.

Back to Rabbi Fohrman. At the end of our parasha (פרק יז) there are two mentions of Avraham’s age (פסוק א and פסוק יז), two renamings (Avraham and Sarah), two ויפל אבר[ה]ם על פניו, two ברכות of children. He even makes a Fohrman-esque pun between (פסוק ו) והפרתי אתך במאד מאד and (פסוק יד) וערל זכר אשר לא ימול…את בריתי הפר, connecting הפרתי with הפר and thematically as the parallel of “having a legacy” and “cutting off the legacy”.

The overall structure is:

A1 Abram is 99 years old: ויהי אברם בן תשעים שנה ותשע שנים

B1 Abram falls on his face: ויפל אברם על פניו

C1 Father of nations: והיית לאב המון גוים

D1 Name change: ולא יקרא עוד את שמך אברם; והיה שמך אברהם

E1 Individuals become nations: והפרתי אתך במאד מאד ונתתיך לגוים

F1 Everlasting covenant: והקמתי את בריתי ביני ובינך ובין זרעך אחריך לדרתם לברית עולם

G1 Promise of land: ונתתי לך ולזרעך אחריך את ארץ מגריך את כל ארץ כנען לאחזת עולם

Center ”You shall keep my covenant“: ואתה את בריתי תשמר אתה וזרעך אחריך לדרתם

G2 Circumcision: המול לכם כל זכר

F2 Everlasting covenant: והיתה בריתי בבשרכם לברית עולם

E2 Individuals cut off from nations: וערל זכר אשר לא ימול…את בריתי הפר

D2 Name change: שרי אשתך לא תקרא את שמה שרי; כי שרה שמה

C2 Mother of nations: וברכתיה והיתה לגוים

B2 Abraham falls on his face: ויפל אברהם על פניו

A2 Abraham is [about to be] 100 years old: ויאמר בלבו הלבן מאה שנה יולד

Now, he has to cheat a little; he skips the last 10 psukim of the perek, which would end the chiasm nicely (with ואברהם בן תשעים ותשע שנה) but the section about ישמעאל doesn’t fit in as well.

But it does help us see what we really did know: בני ישראל are a nation not because of a shared history or land, but because of the בירת. The chiastic structure moves in an “X”, with the role of הקב״ה predominant in the first half (והפרתי אתך, ונתתי לך…את ארץ מגריך) and the role of human beings increasing in the second half (המול לכם כל זכר, את בריתי הפר), centered around the pivot of את בריתי תשמר אתה וזרעך אחריך לדרתם.

The primacy of the covenant speaks to the special nature of Israel’s nationhood. Crack open any history book and read up on how nations come to be. A strongman…manages to aggregate a group of warriors around him, and they conquer a plot of land…A nation is born, and the chief strongman is its king. But that’s not how it worked with us…We were taken out with signs and wonders by…the Master of the Universe Himself and brought into the land of Canaan. We owe our nationhood to no human leader, only to the Divine Master of All.