This shiur is dedicated לעלוי נפש אהרון בן פנחס, Rabbi Arnold Asher.

This week’s parasha tells the story of the end of the 40 years in the wilderness, as בני ישראל approach the Holy Land:

יב משם נסעו; ויחנו בנחל זרד׃ יג משם נסעו ויחנו מעבר ארנון אשר במדבר היצא מגבל האמרי; כי ארנון גבול מואב בין מואב ובין האמרי׃

The story of skirting Moab is told more fully in דברים:

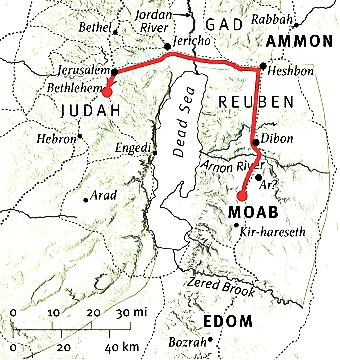

ח ונעבר מאת אחינו בני עשו הישבים בשעיר מדרך הערבה מאילת ומעצין גבר;

ונפן ונעבר דרך מדבר מואב׃ ט ויאמר ה׳ אלי אל תצר את מואב ואל תתגר בם מלחמה; כי לא אתן לך מארצו ירשה כי לבני לוט נתתי את ער ירשה׃…יג עתה קמו ועברו לכם את נחל זרד; ונעבר את נחל זרד׃

יד והימים אשר הלכנו מקדש ברנע עד אשר עברנו את נחל זרד שלשים ושמנה שנה עד תם כל הדור אנשי המלחמה מקרב המחנה כאשר נשבע ה׳ להם׃

יז וידבר ה׳ אלי לאמר׃

יח אתה עבר היום את גבול מואב את ער׃

יט וקרבת מול בני עמון אל תצרם ואל תתגר בם; כי לא אתן מארץ בני עמון לך ירשה כי לבני לוט נתתיה ירשה׃

…כד קומו סעו ועברו את נחל ארנן ראה נתתי בידך את סיחן מלך חשבון האמרי ואת ארצו החל רש; והתגר בו מלחמה׃

The story of what happens on the border of Sichon’s kingdom is told in our parasha:

כא וישלח ישראל מלאכים אל סיחן מלך האמרי לאמר׃

כב אעברה בארצך לא נטה בשדה ובכרם לא נשתה מי באר; בדרך המלך נלך עד אשר נעבר גבלך׃

כג ולא נתן סיחן את ישראל עבר בגבלו ויאסף סיחן את כל עמו ויצא לקראת ישראל המדברה ויבא יהצה; וילחם בישראל׃

כד ויכהו ישראל לפי חרב; ויירש את ארצו מארנן עד יבק עד בני עמון כי עז גבול בני עמון׃

כה ויקח ישראל את כל הערים האלה; וישב ישראל בכל ערי האמרי בחשבון ובכל בנתיה׃

כו כי חשבון עיר סיחן מלך האמרי הוא; והוא נלחם במלך מואב הראשון ויקח את כל ארצו מידו עד ארנן׃

כז על כן יאמרו המשלים באו חשבון; תבנה ותכונן עיר סיחון׃

כח כי אש יצאה מחשבון להבה מקרית סיחן; אכלה ער מואב בעלי במות ארנן׃

כט אוי לך מואב אבדת עם כמוש; נתן בניו פליטם ובנתיו בשבית למלך אמרי סיחון׃

ל ונירם אבד חשבון עד דיבן; ונשים עד נפח אשר עד מידבא׃

לא וישב ישראל בארץ האמרי׃

I have two questions on this paragraph: First, why do we need the history of Sichon? We don’t get any of the history of any of the other nations? It doesn’t seem to affect the actions of בני ישראל. Second, why quote the song? It’s not a Jewish שירה; what’s it doing in the Torah?

The answer to the first question is that we (or at least the original audience of the Torah) knew that ארץ האמרי really was the land of Moab and Amon, and we couldn’t conquer it:

והוא נלחם: לָמָה הוּצְרַךְ לִכָּתֵב? לְפִי שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר ”אַל תָּצֵר אֶת מוֹאָב“, וְחֶשְׁבּוֹן מִשֶּׁל מוֹאָב הָיְתָה, כָּתַב לָנוּ שֶׁסִּיחוֹן לְקָחָהּ מֵהֶם וְעַל יָדוֹ טָהֲרָה לְיִשְֹרָאֵל.

And this will come up 300 years later, in this week’s haftorah:

יב וישלח יפתח מלאכים אל מלך בני עמון לאמר; מה לי ולך כי באת אלי להלחם בארצי׃

יג ויאמר מלך בני עמון אל מלאכי יפתח כי לקח ישראל את ארצי בעלותו ממצרים מארנון ועד היבק ועד הירדן; ועתה השיבה אתהן בשלום׃

…טו ויאמר לו כה אמר יפתח; לא לקח ישראל את ארץ מואב ואת ארץ בני עמון׃

…יח וילך במדבר ויסב את ארץ אדום ואת ארץ מואב ויבא ממזרח שמש לארץ מואב ויחנון בעבר ארנון; ולא באו בגבול מואב כי ארנון גבול מואב׃

…כא ויתן ה׳ אלקי ישראל את סיחון ואת כל עמו ביד ישראל ויכום; ויירש ישראל את כל ארץ האמרי יושב הארץ ההיא׃

כב ויירשו את כל גבול האמרי מארנון ועד היבק ומן המדבר ועד הירדן׃

…כו בשבת ישראל בחשבון ובבנותיה ובערעור ובבנותיה ובכל הערים אשר על ידי ארנון שלש מאות שנה ומדוע לא הצלתם בעת ההיא׃

But why the song? The root משל, meaning parable, only occurs three times in the Torah. Once is our parasha and once is a general expression:

והיית לשמה למשל ולשנינה בכל העמים אשר ינהגך ה׳ שמה׃

Only one person is noted to say משלים:

ז וישא משלו ויאמר; מן ארם ינחני בלק מלך מואב מהררי קדם לכה ארה לי יעקב ולכה זעמה ישראל׃…יח וישא משלו ויאמר; קום בלק ושמע האזינה עדי בנו צפר׃

So Rashi says that this is an introduction to next week’s parasha and its main character:

יאמרו המשלים: בִּלְעָם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר בּוֹ ”וַיִּשָּׂא מְשָׁלוֹ“ (במדבר כג).

המשלים: בִּלְעָם וּבְעוֹר, וְהֵם אָמְרוּ:

בֹּאוּ חֶשְׁבּוֹן: שֶׁלֹּא הָיָה סִיחוֹן יָכוֹל לִכָּבְשָׁה וְהָלַךְ וְשָׂכַר אֶת בִּלְעָם לְקַלֲלוֹ (תנחומא); וְזֶהוּ שֶׁאָמַר לוֹ בָּלָק ”כִּי יָדַעְתִּי אֵת אֲשֶׁר תְּבָרֵךְ מְבֹרָךְ וְגוׂ׳“ (במדבר כב):

And even the expression נלחם במלך מואב הראשון is a hint to next week, when the Torah says that בלק had just been appointed king:

ויאמר מואב אל זקני מדין עתה ילחכו הקהל את כל סביבתינו כלחך השור את ירק השדה; ובלק בן צפור מלך למואב בעת ההוא׃

בעת ההוא: לֹא הָיָה רָאוּי לְמַלְכוּת, מִנְּסִיכֵי מִדְיָן הָיָה, וְכֵיוָן שֶׁמֵּת סִיחוֹן מִנּוּהוּ עֲלֵיהֶם לְצוֹרֶךְ שָׁעָה

But the gemara is bothered by the term משלים, implying that this is a parable or metaphor, and tries to analyze what it could be a metaphor for, with the assumption that there is a lesson that the Torah wants to convey:

א״ר יוחנן: מאי דכתיב (במדבר כא) ”על כן יאמרו המושלים וגו׳“? ”המושלים“ אלו המושלים ביצרם. ”בואו חשבון“ בואו ונחשב חשבונו של עולם: הפסד מצוה כנגד שכרה ושכר עבירה כנגד הפסדה. ”תבנה ותכונן“ אם אתה עושה כן תבנה בעולם הזה ותכונן לעולם הבא. ”עיר סיחון“ אם משים אדם עצמו כעיר זה שמהלך אחר סיחה נאה; מה כתיב אחריו: ”כי אש יצאה מחשבון וגו׳“ תצא אש ממחשבין ותאכל את שאינן מחשבין…

So the original may have been an Emorite victory song, and as such known to בני ישראל, but the Torah includes it here for the lesson from פרקי אבות:

רבי אומר…והוי מחשב הפסד מצוה כנגד שכרה, ושכר עבירה כנגד הפסדה.

והוי מחשב הפסד מצוה: מה שאתה מפסיד מסחורתך וממונך מפני עסק המצוה, כנגד השכר שיעלה לך ממנה בעולם הזה או בעולם הבא, שיהיה יותר מאותו הפסד.

ושכר עבירה: הנאה שאתה נהנה בעבירה, כנגד הפסד שעתיד לבוא לך ממנה.

The problem is the assumption here, that if we were able to overcome our emotions, המושלים ביצרם, then we would make the correct moral calculation and realize that sin is not worth it. But that’s not necessarily true. If we know the penalty then maybe we’ll calculate that its worth it (שכר עבירה כנגד הפסדה). In sports, that’s called an intentional foul:

[Phil Mickelson’s] tee shot was in the fairway, but his second and third shots did not find the green. Soon he had a treacherous, 25-foot downhill putt for bogey. The ball missed the hole and kept going. Mickelson paused, then gave chase like a vexed 30-handicapper. When he caught up to the ball, he whacked it back up the hill and past the hole again.

…For such a serious breach of golf’s rules, Mickelson could have been disqualified from the championship. In a technicality, or a generous rules interpretation by the United States Golf Association, Mickelson was assessed only a two-stroke penalty and allowed to play on.

…Mickelson insisted he had not acted in haste or irritation. Instead, he said, he knew that the penalty for striking a moving ball was two strokes, and he had quickly determined that was a better result than letting his wayward putt roll off the green into worse shape…“I’ve thought about doing the same thing many times in my career,” Mickelson said about striking rather than stopping his moving ball. “I just did it this time. It was something I did to take advantage of the rules as best I can.”

The Netziv looks at our משל as a way to answer that. He starts by retelling the story of Sichon and Moab, noting that Sichon’s fight is in the passive voice:

כִּי חֶשְׁבּוֹן עִיר סִיחֹן מֶלֶךְ הָאֱמֹרִי הִוא; וְהוּא נִלְחַם בְּמֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב הָרִאשׁוֹן וַיִּקַּח אֶת כָּל אַרְצוֹ מִיָּדוֹ עַד אַרְנֹן׃

He proposes that Sichon was invited to fight in Moab but ended up taking over:

במלך מואב הראשון: בשעה שעשו מלך בראשונה. וכמה לא רצו בהנהגת מלוכה. והמה הביאו את סיחון למלחמה על המלך וכבש תחתיו חשבון ובנותיה לעצמו.

(We see this in Jewish history in the Roman occupation of Israel, when Pompey was invited to settle the civil war between Aristobulus and John Hyrcanus)

Then he connects this to the gemara that discusses a עבירה לשמה:

אמר ר״נ בר יצחק: גדולה עבירה לשמה ממצוה שלא לשמה…דכתיב (שופטים ה:כד) תְּבֹרַךְ מִנָּשִׁים יָעֵל אֵשֶׁת חֶבֶר

הַקֵּינִי; מִנָּשִׁים בָּאֹהֶל תְּבֹרָךְ: מאן נשים שבאהל שרה רבקה רחל ולאה. א״ר יוחנן שבע בעילות בעל אותו רשע באותה שעה שנאמר (שופטים ה:כז) בֵּין

רַגְלֶיהָ כָּרַע נָפַל שָׁכָב; בֵּין רַגְלֶיהָ כָּרַע

נָפָל בַּאֲשֶׁר כָּרַע שָׁם נָפַל שָׁדוּד.

והנה לא בחנם נשאו מושלי ישראל דבריהם על הנעשה במואב אם לא להעיר מוסר כמה יש להזהר מאש המחלוקת אשר אפי׳ יחזו מקצת אנשים נכוחות יותר ממי שהקיף מהם; בכ״ז אם ירצו להתחזק על דרכם ע״י חברת מרעים, לעולם לא ישיגו תכלית מבוקשם כי אם יביאו שואה לא ידעו ולא רצו שְׂחָרָהּ. והביאו המשל הזה כי באשר לא רצו המעט בהנהגת מלך. ולא יכלו להתגבר על הרוב אשר הקימוהו למלך. מה עשו קראו לסיחון לבא חשבון. והוא העלה שואה על המדינה והחריב העיר ובנאה לעצמו.

ונראה דלזה כוונו חז״ל בב״ב עח,ב דאר״י מ״ד על כן יאמרו המושלים באו חשבון… מה צריכין לחשבון זה? הלא גם בלי זה החשבון ראוי למשול ביצרו ולא לעבור ע״ד ה׳! ותו מה זה חשבון הנאת עבירה נגד עונש עוה״ב הרוחני? אלא לא דברו כאן בענינים שבין אדם לשמים. אלא בעניני הליכות עולם. דיש עושים מחלוקת בשביל שרוצה לעשות מצוה שגורם בזה לידי מחלוקת ויש מחשב לרדוף את הרשע או את הצבור בשביל איזה עול. ואע״ג שהוא עבירה לרדוף מכ״מ מחשב שיקבל שכר על עבירה לשמה כדאיתא במסכת נזיר דף כג ”גדולה עבירה לשמה כו׳“. הנה אם אינו מושל ביצרו ומכוין לש״ש…אך אפילו הוא מושל ביצרו ומכוין אך לשם שמים עדיין עליו לבא חשבונו ש״ע. אם כדאי הפסד מצוה שיגיע ע״י שיעשה נגד שכרה כי יכול להיות שההפסד שיגיע ע״י המחלוקת רבה על השכר ממנה. ושכר עבירה לשמה שמכוין נגד הפסדה שיגיע אח״כ עי״ז. ובאו חז״ל לזה המוסר בדבר שאירע כמו כן באנשי מואב שכוונו לטובת הכלל להביא את סיחון אבל לא באו חשבונו ש״ע מה שיהיה יוצא מזה. ובא ע״ז משל הקדמוני מסוים בתורה ללמדנו דעת שלא לעשות עבירה לשמה. ובזה נכלל רדיפה לאדם ומחלוקת אם לא שיהיה מושל ביצרו. וגם באו חשבון ברור.

The problem of הוי מחשב הפסד מצוה כנגד שכרה, ושכר עבירה כנגד הפסדה is not for those who act without thinking. It’s for those who carefully, rationally analyze the situation and decide that an עבירה לשמה. The Netziv (who was no stranger to מחלקת) points out that too often we decide to fight לשם שמים, not realizing that what inevitably happens is אש יצאה מחשבון and destroys everything in its path.