Last week we discussed the connection between נקב שם ה׳ and עין תחת עין, and proposed that both are part of ברית סיני, that even civil laws require revelation to be morally binding. Mickey Ariel mentioned that the Rambam, at least, feels that some laws can be derived by observation of the world around us. This is called the doctrine of “natural law”: that if we are careful and rational philosophers, we can deduce moral law. This is called “ethics”, the philosophical question not of what is real, but what is right. The idea comes from Greek and Roman philosophers (who didn’t believe in a just deity):

But if the judgments of men were in agreement with Nature…then Justice would be equally observed by all. For those creatures who have received the gift of reason from Nature have also received right reason, and therefore they have also received the gift of Law, which is right reason applied to command and prohibition.

The other side is the nihilist side, that there is no inherent ethic in the universe, just our individual needs:

[W]hatsoever is the object of any mans Appetite or Desire; that is it, which

he for his part calleth Good: And the object of his Hate, and Aversion,

Evill; And of his Contempt, Vile, and Inconsiderable. For these words of

Good, Evill, and Contemptible, are ever used with relation to the person

that useth them: There being nothing simply and absolutely so; nor any

common Rule of Good and Evill, to be taken from the nature of the

objects themselves…

Within a religious perspective, the question has been put more succinctly:

Are morally good acts willed by G-d because they are morally good, or are they morally good because they are willed by G-d?

And in the Jewish perspective, the question is:

Does Jewish tradition recognize an ethic independent of Halakha?

Note that we assume that Halakha, broadly defined, includes all good; that is, there is no ethic outside of Halakha. The question is, are there any ethical precepts that we would be bound to obey even if they were not explicitly commanded, that is, are they independent of Halakha?

The question has been long debated, and I won’t solve it now (my own answer is based on the פחד יצחק חנוכה מאמר ז׳; ואכמ״ל). There is another question, though, of what did the Rambam actually hold. See the articles by Rav Aharon Lichtenstein (who says Rambam did believe in natural law) and Professor Marvin Fox (who says he did not), cited above. The Rambam never directly addresses the issue. There is one place where it is relevant, in the laws of חסידי אומות העולם, and there the argument hinges on a single letter:

כל המקבל שבע מצוות, ונזהר לעשותן—הרי זה מחסידי אומות העולם, ויש לו חלק לעולם הבא; והוא שיקבל אותן ויעשה אותן, מפני שציווה בהן הקדוש ברוך הוא בתורה, והודיענו על ידי משה רבנו, שבני נוח מקודם נצטוו בהן. אבל אם עשאן מפני הכרע הדעת—אין זה גר תושב, ואינו מחסידי אומות העולם [אלא][ולא] מחכמיהם.

There are manuscripts that go both ways—אלא and ולא—so all we are left with is the argument.

That was from last week. Now I want to talk about this week’s parasha, and the end of the תוכחה:

מג והארץ תעזב מהם ותרץ את שבתתיה בהשמה מהם והם ירצו את עונם; יען וביען במשפטי מאסו ואת חקתי געלה נפשם׃

מד ואף גם זאת בהיותם בארץ איביהם לא מאסתים ולא געלתים לכלתם להפר בריתי אתם; כי אני ה׳ אלקיהם׃

This is an insight from Avigdor Bonchek, What’s Bothering Rashi: Vayikra. What does זאת mean in that last pasuk? “Despite this, I have not been revolted by them”. Despite what?

אף גם זאת: ואף אפילו אני עושה עמהם זאת הפורענות אשר אמרתי בהיותם בארץ אויביהם, לא אמאסם לכלותם ולהפר בריתי אשר אתם.

Rashi explains זאת as “Despite all these punishments”. Now, that’s not how I would have explained it. The parallel to לא מאסתים ולא געלתים…להפר בריתי אתם seems to be in the description of our behavior:

ואם בחקתי תמאסו ואם את משפטי תגעל נפשכם לבלתי עשות את כל מצותי להפרכם את בריתי׃

In other words, זאת refers to our rejection of G-d, and ואף גם זאת means, “despite Israel’s despising Me, I will not despise them”. But that’s not how the word זאת is used in the rest of the תוכחה:

אף אני אעשה זאת לכם והפקדתי עליכם בהלה את השחפת ואת הקדחת מכלות עינים ומדיבת נפש; וזרעתם לריק זרעכם ואכלהו איביכם׃

כז ואם בזאת לא תשמעו לי; והלכתם עמי בקרי׃

כח והלכתי עמכם בחמת קרי; ויסרתי אתכם אף אני שבע על חטאתיכם׃

אף אני אעשה זאת can’t mean “I will reject them” since ה׳ says explicitly that He will not reject them. So Rashi explains ואף גם זאת…לא מאסתים ולא געלתים לכלתם להפר בריתי אתם as “despite my punishing them and despising them, it was not to the extent of destroying them or breaking the ברית”.

The Meshech Chochma is then bothered by the wording of לכלתם להפר בריתי אתם, which seems to mean “in order to destroy them or break the ברית”, then says that this is exactly what the pasuk means: “I despised them not in order to destroy them but because אני ה׳ אלקיהם”. The punishments of the תוכחה, the זאת of our pasuk, are for our benefit. When the Jews feel at peace in the גלות, ה׳ makes sure we cannot assimilate:

והנה מעת היות ישראל בגויים, ברבות השנים, אשר לא האמינו כל יושבי תבל…אשר שטפו באלפי שנים על עם המעט והרפה כח וחדל אונים…הנה דרך ההשגחה כי ינוחו משך שנים קרוב למאה או מאתיים. ואחר זה יקום רוח סערה, ויפוץ המון גליו…עד כי נפזרים בדודים, ירוצו יברחו למקום רחוק, ושם יתאחדו, יהיו לגוי, יוגדל תורתם, חכמתם יעשו חיל, עד כי ישכח היותו גר בארץ נכריה, יחשוב כי זה מקום מחצבתו, בל יצפה לישועת ה׳ הרוחניות בזמן המיועד. שם יבא רוח סערה עוד יותר חזק, יזכיר אותו בקול סואן ברעש—”יהודי אתה ומי שמך לאיש, לך לך אל ארץ אשר לא ידעת“!

He famously made the prediction that even Germany, the epitome of culture and learning (he’s writing in the 1870’s), would not be safe for the Jews:

עוד מעט ישוב לאמר ”שקר נחלו אבותינו“, והישראלי בכלל ישכח מחצבתו ויחשב לאזרח רענן. יעזוב לימודי דתו, ללמוד לשונות לא לו, (תלמוד ירושלמי מועד קטן ב:ב ח,ב) יליף מקלקלתא ולא יליף מתקנא, יחשוב כי ברלין היא ירושלים, וכמקולקלים שבהם עשיתם כמתוקנים לא עשיתם…אז יבוא רוח סועה וסער, יעקור אותו מגזעו יניחהו לגוי מרחוק אשר לא למד לשונו, ידע כי הוא גר.

That idea is pretty commonplace now. But the interesting point is that he says the problem is not the economic comfort of גלות, but the intellectual complacency:

כי כאשר ינוח ישראל בעמים יפריח ויגדל תורתו ופלפולו, ובניו יעשו חיל, יתגדרו נגד אבותיהם, כי ככה חפץ האדם אשר האחרון יחדש יוסיף אומץ מה שהיה נעלם מדור הישן. וזה בחכמות האנושית, אשר מקורן מחצבת שכל האנושי והנסיון, בזה יתגדרו האחרונים יוסיפו אומץ, כאשר עינינו רואות בכל דור. לא כן הדת האלוקי הניתן מן השמים, ומקורו לא על ארץ חוצב. הלא אם היה בארץ ישראל מלפנים, הלא היה להם להתגדר בתיקון האומה כל אחד לפי דורו—בית דין הגדול היה יכול לבטל את דברי בית דין הקודם…ומלבד זה היה תמיד הופעה אלקית רוחנית, מלבד מקדש ראשון, ששרה עליהם הרוח, והיו נביאים ובני נביאים…אף במקדש שני אמרו ששם שואבים רוח הקודש, והיה גלוי אור אלקי תמיד חופף…

לא כן בגולה, שנתמעט הקיבוץ והאסיפה בלימוד התורה, שמטעם זה אין רשות לשום בית דין לחדש דבר…ואין שום חוזה ונביא, ומחיצה של ברזל מפסקת בין ישראל לאביהם שבשמים. כך היה דרכה של האומה, שכאשר יכנסו לארץ נכריה, יהיו אינם בני תורה, כאשר נדלדלו מן הצרות והגזירות והגירוש, ואח״כ יתעורר בהם רוח אלקי השואף בם להשיבם למקור חוצבו מחצבת קדשם, ילמדו, ירביצו תורה, יעשו נפלאות, עד כי יעמוד קרן התורה על רומו ושיאו. הלא אין ביד הדור להוסיף מה, להתגדר נגד אבותם! מה יעשה חפץ האדם העשוי להתגדר ולחדש? יבקר ברעיון כוזב את אשר הנחילו אבותינו, ישער חדשות בשכוח מה היה לאומתו בהתנודדו בים התלאות, ויהיה מה. עוד מעט ישוב לאמר ”שקר נחלו אבותינו“…

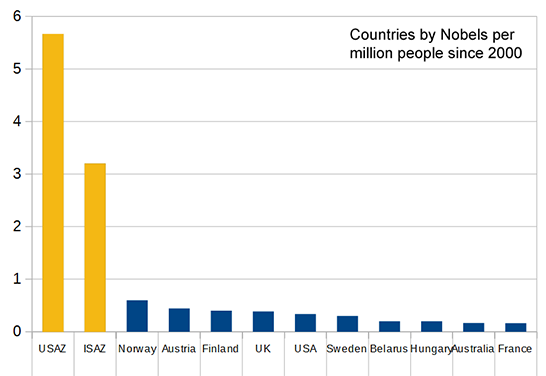

I find this an amazing idea. Jews are smart (USAZ is “Ashkenazi Jews in the US”, ISAZ is “Ashkenazi Jews in Israel”; the author is trying to make a point about genetics):

But the Meshech Chochma says that’s a side effect of our true purpose, which is to learn Torah. We are driven to produce חידושים in Torah, but there’s no real Torah in גלות. That’s the real punishment of the תוכחה: we lose out connection to ה׳, and can’t learn anymore. So we branch out into other intellectual fields, and dominate them, and think ברלין היא ירושלים. Then ה׳ uproots us and in the chaos of yet another exile we forget even the Torah we knew, and have to rebuild Torah institutions in our new home, and that serves to satisfy our intellectual needs until אחרית הימים when we can produce real חידושים again:

אז יבוא רוח סועה וסער, יעקור אותו מגזעו יניחהו לגוי מרחוק אשר לא למד לשונו, ידע כי הוא גר, לשונו שפת קדשנו, ולשונות זרים כלבוש יחלוף, ומחצבתו הוא גזע ישראל, ותנחומיו ניחומי נביאי ה׳, אשר ניבאו על גזע ישי באחרית הימים. ובטלטולו ישכח תורתו, עומקה ופלפולה, ושם ינוח מעט, יתעורר ברגש קודש, ובניו יוסיפו אומץ, ובחוריו יעשו חיל בתורת ה׳, יתגדרו לפשט תורה בזה הגבול, אשר כבר נשכחה, ובזה יתקיים ויחזק אומץ. כה דרך ישראל מיום היותו מתנודד…

וזה ”לא מאסתים“—מיאוס הוא על שפלות האומה בתורה והשכלה הרוחנית המופעת מתורתנו הכתובה והמסורה. ”לא געלתים“—הוא על גיעול ופליטה ממקום למקום. ”לכלותם“—הוא על הגלות שזה גיעול וכליון חרוץ להאומה. ”להפר בריתי אתם“—הוא על שכחות התורה. רק ”כי אני ה׳ אלקיכם“, רצונו לומר, שהגיעול והמיאוס הוא סיבה שאני ה׳ אלקיהם. אבל לא מיאוס וגיעול מוחלטת ”לכלותם ולהפר בריתי אתם“ חלילה. שעל ידי זה יתגדל שמו ויתקיים גוי זרע אברהם, זרע אמונים, ראוי ועומד לקבל המטרה האלקית, אשר יקרא ה׳ לנו באחרית הימים בהיות ישראל גוי אחד בארץ, והיה ה׳ אחד ושמו אחד.

This is a very Zionist idea, that Torah can only truly be learned in ארץ ישראל:

וזהב הארץ ההיא טוב, מלמד שאין תורה כתורת א״י ולא חכמה כחכמת א״י.

אמר רבי זירא שמע מינה אוירא דארץ ישראל מחכים.

And I will conclude with the words of Rav Kook:

הַדִּמְיוֹן שֶׁל אֶרֶץ־יִשְׂרָאֵל הוּא צָלוּל וּבָרוּר, נָקִי וְטָהוֹר וּמְסֻגָּל לְהוֹפָעַת הָאֱמֶת הָאֱ־לֹהִית, לְהַלְבָּשַׁת הַחֵפֶץ הַמְרוֹמָם וְהַנִּשְׂגָּב שֶׁל הַמְּגַמָּה הָאִידֵאָלִית אֲשֶׁר בְּעֶלְיוֹנוּת הַקֹּדֶשׁ, מוּכָן לְהַסְבָּרַת נְבוּאָה וְאוֹרוֹתֶיהָ, לְהַבְהָקַת רוּחַ־הַקֹּדֶשׁ וּזְהָרָיו. וְהַדִּמְיוֹן אֲשֶׁר בְּאֶרֶץ הָעַמִּים עָכוּר הוּא, מְעֹרָב בְּמַחֲשַׁכִּים, בְּצִלְלֵי טֻמְאָה וְזִהוּם, לֹא יוּכַל לְהִתְנַשֵּׂא לִמְרוֹמֵי קֹדֶשׁ וְלֹא יוּכַל לִהְיוֹת בָּסִיס לְשִׁפְעַת הָאוֹרָה הָאֱ־לֹהִית הַמִּתְעַלָּה מִכָּל שִׁפְלוּת הָעוֹלָמִים וּמְצָרֵיהֶם. מִתּוֹךְ שֶׁהַשֵּׂכֶל וְהַדִּמְיוֹן אֲחוּזִים זֶה בָּזֶה וּפוֹעֲלִים וְנִפְעָלִים זֶה עַל זֶה וְזֶה מִזֶּה, לָכֵן לֹא יוּכַל הַשֵּׂכֶל גַּם שֶׁבְּחוּץ־לָאָרֶץ לִהְיוֹת מֵאִיר בְּאוֹרוֹ שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ־יִשְׂרָאֵל. ”אֲוִירָא דְּאֶרֶץ־יִשְׂרָאֵל מַחְכִּים“.